The United States of America (USA or U.S.A.), commonly known as the United States (US or U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. The third-largest country in the world by land and total area,[c] the U.S. is a federal republic of 50 states, with its capital in a separate a federal district, and 326 Indian reservations that overlap with state boundaries. It also has five major unincorporated territories, and seven undisputed plus four disputed Minor Outlying Islands.[i]. It shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south and has maritime borders with several other countries.[j] With a population of over 334 million,[k] it is the third-most populous country in the world. The national capital is Washington, D.C., and its most populous city and principal financial center is New York City.

Healthcare in the United States is largely provided by private sector healthcare facilities, and paid for by a combination of public programs, private insurance, and out-of-pocket payments. The U.S. is the only developed country without a system of universal healthcare, and a significant proportion of its population lacks health insurance.

The U.S. healthcare system has been the subject of significant political debate and reform efforts, particularly in the areas of healthcare costs, insurance coverage, and the quality of care. Legislation such as the Affordable Care Act of 2010 has sought to address some of these issues, though challenges remain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States

- GLOBAL PRETERM BIRTH RATES – USA

- Estimated # of preterm births: 9.56 per 100 live births

- (Global Average: 10.6)

- Source- WHO 2023- https://ptb.srhr.org/https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2023-1-in-10-babies-worldwide-are-born-early–with-major-impacts-on-health-and-survival

COMMUNITY

The 2024 Mom and Baby Action Network Summit Igniting Impact Together: Nurturing Collaborative Solutions

June 10 & 11, 2024 Marriott Marquis Chicago, Illinois

The 2024 Mom and Baby Action Network Summit will be a multi-day, multi-track, in-person conference to bring together existing and prospective M-BAN members, community partners, funders, philanthropists, and March of Dimes mission staff to learn, network, celebrate, be inspired, commit, and take action to advance equity in maternal and infant health.

LET”S FOCUS ON PREVENTION

Foods we eat are covered in plastics that may be causing a rise in premature births, study says

By Sandee LaMotte, CNN – 02:23 – Source: CNN

Premature births are on the rise, yet experts aren’t sure why. Now, researchers have found synthetic chemicals called phthalates used in clear food packaging and personal care products could be a culprit, according to a new study.

Past research has demonstrated that phathalates — known as “everywhere chemicals” because they are so common — are hormone disruptors that can impact how the life-giving placenta functions. This organ is the source of oxygen and nutrients for a developing fetus in the womb.

“Phthalates can also contribute to inflammation that can disrupt the placenta even more and set the steps of preterm labor in motion,”said lead author Dr. Leonardo Trasande, directorof environmental pediatrics at NYU Langone Health.

“Studies show the largest association with preterm labor is due to a phthalate found in food packaging calledDi(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, or DEHP,” Trasande said. “In our new study, we found DEHP and three similar chemicals could be responsible for 5% to 10% of all the preterm births in 2018. This could be one of the reasons why preterm births are on the rise.”

The5% to 10% percentagetranslated into nearly 57,000 preterm births in the United States during 2018, at a cost to society of nearly $4 billion in that year alone, according to the study, published Tuesday in the journal Lancet Planetary Health.

“This paper focused on the relationship between exposure to individual phthalates and preterm birth. But that’s not how people are exposed to chemicals,” said Alexa Friedman, a senior scientist of toxicology at the Environmental Working Group, or EWG, in an email.

“Every day, they’re often exposed to more than one phthalate from the products they use, so the risk of preterm birth may actually be greater,” said Friedman, who was not involved in the study.

The American Chemistry Council, an industry trade association for US chemical companies, told CNN the report did not establish causation.

“Not all phthalates are the same, and it is not appropriate to group them as a class. The term ‘phthalates’ simply refers to a family of chemicals that happen to be structurally similar, but which are functionally and toxicologically distinct from each other,” a spokesperson for the council’s ’s High Phthalates Panel wrote in an email.

‘Everywhere chemicals’

Globally, approximately 8.4 million metric tons of phthalates and other plasticizers are consumed every year, according to European Plasticisers, an industry trade association.

Manufacturers add phthalates to consumer products to make the plastic more flexible and harder to break, primarily in polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, products such as children’s toys.

Phthalates are also found in detergents; vinyl flooring, furniture and shower curtains; automotive plastics; lubricating oils and adhesives; rain and stain-resistant products; clothing and shoes; and scores of personal care products including shampoo, soap, hair spray and nail polish, in which they make fragrances last longer.

Studies have connected phthalates to childhood obesity, asthma, cardiovascular issues, cancer and reproductive problems such as genital malformations and undescended testes in baby boys and low sperm counts and testosterone levels in adult males.

“The Consumer Product Safety Commission no longer allows eight different phthalates to be used at levels higher than 0.1% in the manufacture of children’s toys and child care products,” Trasande said. “However, not all of the eight have been limited in food packaging by the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration).”

In response to governmental and consumer concerns, manufacturers may create new versions of chemicals that no longer fall under any restrictions. Take DEHP, for example, which has been replaced by newer phthalates called di-isodecylphthalate (DiDP), di-n-octyl phthalate (DnOP), and diisononyl phthalate (DiNP).

Are those safer than the original? That’s not what scientists say they typically discover as they spend years and thousands of dollars to test the newcomers.

“Why would we think that you can make a very minor change in a molecule you are manufacturing and the body wouldn’t react in the same way?” asked toxicologist Linda Birnbaum, former director of the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, as well as the National Toxicology Program. She, too, was not involved in the paper.

“Phthalates should be regulated as a class (of chemicals). Many of us have been trying to get something done on this for years,” Birnbaum said in an email.

Even more dangerous swaps

The new research used data from the National Institutes of Health’s Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes, or ECHO, study, which investigates the impact of early environmental influences on children’s health and development. In 69 sites around the country, expectant mothers and their newborns are evaluated and provide blood, urine and other biological samples to be analyzed.

The team identified 5,006 pregnant mothers with urine samples that tested positive for different types of phthalates and compared those with the baby’s gestational age at birth, birthweight and birth length.

Data was also pulled from the 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a government program that assesses the health and nutritional status of Americans using a combination of interviews, physical examinations and laboratory analysis of biological specimens.

After analyzing the information, Trasande and his coauthors were able to confirm past research showing a significant association of DEHP with shorter pregnancies and preterm birth.

Interestingly, however, the research team found the three phthalates created by manufacturers to replace DEHP were actually more dangerous than DEHP when it came to preterm birth.

“When we looked further into these replacements, we found even stronger effects of DiDP, DnOP and DiNP,” Trasande said. “It took less of a dose in order to create the same outcome of prematurity.”

Dangers of prematurity

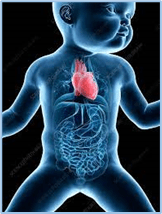

A birth is considered preterm if it occurs before 37 weeks of gestation — a full-term pregnancy is 40 weeks or more. Because vital organs and part of the nervous system may not be fully developed, a premature birth may place the baby at risk. Babies born extremely early are often immediately hospitalizedto help the infant breathe and address any heart, digestive and brain issues or an inability to fight off infections.

As they grow up, children born prematurely may have vision, hearing and dental issues, as well as intellectual and developmental delays, according to the Mayo Clinic. Prematurity can contribute to cerebral palsy, epilepsy,and mental health disorders such as anxiety, bipolar disorder and depression.

As adults, people born prematurely may also have higher blood pressure and cholesterol, asthma and other respiratory infections and develop type 1 and type 2 diabetes, heart disease, heart failure or stroke.

All of these medical expenses add up, allowing Trasande and his coauthors to estimate the cost to the US in medical care and lost economic productivity from preterm births to be “a staggering $3.8 billion,” said EWG’s Alexa Friedman.

“But the real cost lies in the impact on infants’ health,” Friedman said.

There are additional steps one can take to reduce exposure to phthalates and other chemicals in food and food packaging products, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ policy statement on food additives and children’s health.

“One is to reduce our plastic footprint by using stainless steel and glass containers, when possible,” said Trasande, who was lead author for the AAP statement.

“Avoid microwaving food or beverages in plastic, including infant formula and pumped human milk, and don’t put plastic in the dishwasher, because the heat can cause chemicals to leach out,” he added. “Look at the recycling code on the bottom of products to find the plastic type, and avoid plastics with recycling codes 3, which typically contain phthalates.”

https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/06/health/preterm-birth-phthalates-study-wellness/index.html

Olivia Rodrigo – Vampire (Live From iHeartRadio Jingle Ball 2023)

**********************************************************

The 3 NEONATAL (cyanotic) CARDIAC emergencies you NEED to know

Tala Talks NICU 6,508 views Dec 19, 2022 Cardiac

You are about to attend a delivery of a prenatally diagnosed cardiac patient: when do you need to immediately alert the cardiologists/ transport team/ cardiac surgeons? We discuss 3 cardiac lesions which may need immediate intervention.

Dr. Tala is a board-certified neonatologist and has worked in busy level III and IV units for the past 15 years. She has won multiple teaching awards throughout her time as a neonatologist.

HEALTHCARE PARTNERS

Neurodevelopmental, Mental Health, and Parenting Issues in Preterm Infants

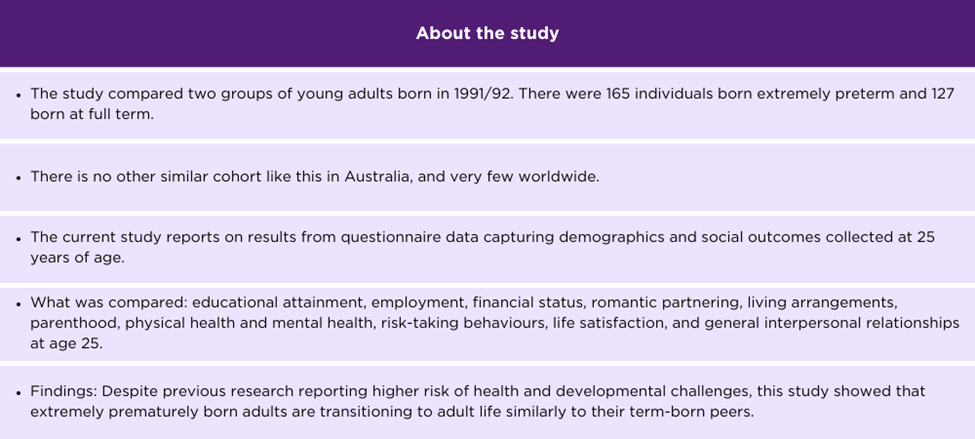

Abstract

The World Health Organization in its recommendations for the care of preterm infants has drawn attention to the need to address issues related to family involvement and support, including education, counseling, discharge preparation, and peer support. A failure to address these issues may translate into poor outcomes that extend across the lifespan. In this paper, we review the often far-reaching impact of preterm birth on the health and wellbeing of the parents and highlight the ways in which psychological stress may have a negative long-term impact on the parent-child interaction, attachment, and the styles of parenting. This paper addresses the following topics: (1) neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants, including cognitive, sensory, and motor difficulties, (2) long-term mental health issues in premature infants that include elevated rates of anxiety and depressive disorders, autism, and somatization, which may affect social relationships and quality of life, (3) adverse mental health outcomes for parents that include elevated rates of depression, anxiety, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress, as well as increased rates of substance abuse, and relationship strain, (4) negative impacts on the parent-infant relationship, potentially mediated by maternal sensitivity, parent child-interactions, and attachment, and (5) impact on the parenting behaviors, including patterns of overprotective parenting, and development of Vulnerable Child Syndrome. Greater awareness of these issues has led to the development of programs in neonatal mental health and developmental care with some data suggesting benefits in terms of shorter lengths of stay and decreased health care costs.

1.Introduction

Global estimates of preterm (<37 weeks gestation) and low birth weight (LBW) infants range from 15–20% of all live births. Infants in this category have a two- to 10-fold higher risk of mortality than the term and normal birth weight infants and are at greater risk of medical complications and developmental problems including growth failure and developmental disabilities. Preterm birth rates decreased between 2007–2014 but have increased since that date with one in 10 babies in the US being born prematurely. Rates of prematurity and low birth weight vary depending on race and ethnicity with higher rates in Black women .

While much attention has been focused on the medical and developmental issues of preterm infants, an appreciation of the psychological impact of the preterm birth and the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) experience on the parents has been less well studied. This is reflected in the hospital NICU practices that have emphasized interventions to improve infant outcomes rather than the psychological health of the parents. However, the recent World Health Organization Recommendations for Care of the Preterm or Low-Birth-Weight Infant [3] have drawn attention to the need to address the issues related to family involvement and support including education, counseling, discharge preparation, and peer support.

The birth and hospitalization of a preterm or LBW infant in the NICU is typically an unexpected and traumatic experience for parents. Parents frequently report feelings of guilt, anxiety, and sadness about the loss of the “perfect” child. Sources of stress include aspects of the NICU environment, unexpected physical characteristics and behaviors of the infant, difficult interactions with NICU staff, and the inability to take on the expected parenting role. The psychological models used to explain parental reactions include those of grief and loss, but also the trauma model, in which the baby’s preterm birth is experienced as a traumatic event.

In this paper, we review the often far-reaching impact of preterm birth on the health and wellbeing of the parents and highlight the ways in which psychological stress may have a negative long-term impact on parent-child interaction, attachment, and styles of parenting. A failure to recognize these issues may translate into poor outcomes that may extend across the lifespan.

2. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

To provide a context to the impact of preterm birth, we start with a review of neurodevelopmental outcomes in the preterm infants. As improvements in survival have occurred among preterm infants, focus has shifted somewhat from preventing mortality to reducing neurodevelopmental impairment [5,6]. In the second half of gestation, brain volumes increase over 10-fold, making this a particularly vulnerable stage for neurological injury and disordered development . The brains of preterm infants over time may show poor oligodendrocyte maturation, delayed myelination and neurite formation, and glial activation . Rates of cognitive, motor, and sensory impairments are higher among preterm born than term born children and have been studied extensively. The highest rates of impairment occur among the most premature, although even late preterm and early term born children may have outcomes below term norms. In a meta-analysis of studies performed after 2000, the rates of cognitive and motor delays were found in roughly 16% and 20% of preterm born children with mild delays being more frequent than moderate to severe delays. Among those extremely preterm (EPT: born at less than 28 weeks gestation) and very preterm (VPT: born between 28–31 weeks gestation), the rates are higher and estimated to be 52% and 24%, respectively, in an international cohort .

It is important to note that challenges exist in interpreting the existing data regarding neurodevelopmental outcomes due to a variation in the individual center approaches to high-risk infants , varying definitions of impairment in the literature, changes in testing models, and a limited predictability of early-stage testing to predict school age outcomes . There is a relative paucity of data on neurodevelopmental outcomes up to school age with some concern that early estimates of cognitive and motor impairment may underestimate issues identifiable at later ages. In addition, the post discharge care environment may have a profound impact on the developmental trajectories, particularly for the highest risk infants.

Specific neurodevelopmental challenges among former preterm children include abnormalities of motor, cognitive, and sensory capabilities. A composite of these three factors, often a combination of Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) cognitive and motor scores and sensory impairment data, is commonly used as a primary outcome in neonatal research but misses other important challenges faced by preterm born children. Social, attentional, executive function, and communication skills may be undermeasured, either due to a test construct or the age of administration, but may represent more important functional and life-impacting issues to children and families. Attention has been brought by former NICU families on the need to include factors valued by the family, or those themselves who were born preterm, in the delineation of research outcomes.

Motor disturbances were among the earliest described and may encompass both cerebral palsy (CP), and movement disorders. The rates of CP have fallen in recent years with an estimate of 6.8% in preterm born children, down from previous estimates of ~11% in more historical cohorts. Higher rates of CP are found in EPT-born children but have similarly fallen from estimates of ~14% to 10%. The rates of overall motor delay are higher than of CP, being up to 44% of EPT children and 16% of VPT children with moderate to severe delays in 11% and 6%, respectively. Although movement disorders may be ameliorated by therapies, some may have a significant impact on daily living activities and are associated with an increased risk of reading and attention issues, speech and language impairment, and social-emotional problems.

Sensory impairments, including profound hearing and vision impairment, are less frequent than cognitive and motor delays but may have important long-term consequences for the preterm infant. Bilateral hearing impairment requiring intervention occurs in 1–9% of preterm infants. As auditory input is important for language development, a failure to recognize and mitigate the deficits may have a significant impact on functional abilities and academic performance. Visual impairments, including acuity, convergence, and strabismus issues, are also more common in preterm infants and may lead to academic challenges .

Cognitive disabilities represent the most common neurodevelopmental impairment and may include difficulties in executive function, language processing, and working memory. The rates of cognitive neurodevelopmental impairment are more common in EPT children with a pooled prevalence of 29% in recent studies, and 10.9% being moderate or severe. VPT children in this same review had a 14% rate of cognitive impairment with 5.8% being moderate or severe. Language skills are often commonly affected with VPT children who are eight times more likely to exhibit a poorer language trajectory during development. IQ scores are 12–13 points lower than term infants in VPT born children [38] and up to 25 points lower for children born less than 26 weeks gestation.

Intelligence tests may fail to detect other issues that are important to cognitive function, including executive function, and a collection of abilities related to goal-direction and adaptive behavior. The included domains are working memory, impulse control, cognitive flexibility, planning, and organization. EPT children have higher rates of executive dysfunction at school age, particularly in working memory, planning, and organization. Working memory, in particular, is a strong, independent predictor of academic achievement, even after accounting for IQ. Attention disorders are more common among preterm infants and may significantly impact academic performance. VPT children have shown higher levels of attention problems, social impairment, and compromised communication skills than their term born counterparts .

3. Speech and Language Delays

Children born preterm demonstrate an increased risk for poor outcomes in language development. Early difficulties with language have been documented across all degrees of prematurity, including among children born extremely preterm, moderately and late preterm, late preterm, and preterm or at a low birthweight. Children born preterm display difficulties on the measures of receptive language , expressive language, receptive and expressive language considered together , and articulation. While an extensive literature documents the challenges that children born preterm experience with the acquisition of language skills, there is a paucity of research that has investigated how to mitigate the risk of prematurity on language development during the earliest opportunity to intervene—in the NICU environment. More research is needed on NICU-based language interventions to provide children born preterm with a robust foundation from which to build language competence.

4. Infant Mental Health Outcomes

Children born preterm demonstrate a heightened risk for a wide range of mental health and neurodevelopmental conditions. A variety of psychobiological factors have been implicated in the development and maintenance of these conditions. An appreciation of both the risk for and complexity of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental concerns can support the delivery of effective, tailored care to children born preterm.

4.1. Internalizing and Externalizing Disorders

Children born preterm may display behavioral difficulties as they progress through childhood, however, research findings in the literature are mixed. Several unique behavioral profiles have been detected. Some children born preterm may show the highest levels of behavioral problems in the period between two and three years of age. However, Bosch and colleagues found limited behavioral challenges among two-year-olds with a history of preterm birth. Some children born preterm may show few externalizing and internalizing behaviors, with relatively more internalizing behaviors as they age.

Variables that account for the outcomes in behavioral concerns include gestational age, skin-breaking procedures and morphine administration in the NICU, maternal depression, parenting stress, caregiver hostility, parental view of child vulnerability, and socioeconomic status. The emerging research has focused on investigating the neural correlates of behavioral difficulties of the children born preterm. Results from Gilchrist and colleagues have revealed that decreased neural network integration is linked to greater internalizing challenges when children are seven years of age.

Heightened risk for psychiatric disorders has been reported in the literature, although findings have been inconsistent. Among three- to six-year-olds, late preterm birth has been shown to relate to elevated odds of developing an anxiety disorder. Late preterm birth has also been linked to elevated teacher reports of attention and internalizing concerns at six years. Individuals born preterm display 1.5–2.9 times greater odds of developing depression, 2.7–7.4 times greater odds of developing bipolar disorder, and 1.6–2.5 times greater odds of developing psychosis. The findings from Upadhyaya et al. similarly demonstrate heightened risk for depression between the ages of 5 and 25 years in individuals born preterm. A history of preterm birth has also been found to relate to elevated odds of psychiatric hospitalization later in life. Lower gestational age has been found to be linked to higher odds of psychiatric hospitalization. However, in a report from Burnett and colleagues on adolescents, mood and anxiety disorders were present at comparable levels between subjects who had been born preterm and subjects who served as controls.

4.2. Social Relationships and Autism

The extant literature has demonstrated a link between a history of preterm birth and social functioning. At seven to nine months of age, children born preterm demonstrate lowered social attentional preference relative to children born full term, although this difference is no longer present at five years. Preterm birth is also related to an elevated risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). One report indicates a prevalence rate of ASD of 28–40% in a local sample of adolescents with a history of preterm birth. Research from Chang and colleagues has demonstrated that earlier gestational age is linked with an elevated risk for ASD. Among the children with ASD, the children born preterm show poorer nonverbal behaviors but better socioemotional reciprocity and peer relationships relative to the children born full term. The candidate etiological pathways for the onset of ASD in children born preterm are underlying inflammatory and genetic processes.

4.3. Somatization

Given that children born preterm undergo a multitude of painful procedures over the course of a NICU admission, it is critical to understand the degree to which early, concentrated experiences of pain are related to later pain processing and management. Grunau and colleagues have found that young children with a history of extremely low birth weight and preterm birth demonstrate clinically elevated levels of somatization. Variables that have been found to relate to somatization in the children born preterm include family relations, maternal sensitivity, and NICU admission history.

4.4. Quality of Life

Quality of life is an important consideration when caring for infants born preterm who have a greater likelihood of enduring the painful and extensive medical interventions from the earliest moments of life. An examination of the quality of life of individuals born preterm has resulted in mixed findings, depending in part on the source of data and the age of the subjects. The parents of children born preterm have indicated a lower quality of life for their children at 10 years of age as compared to the parents of children born full-term. Subject- and caregiver assessment of quality of life has demonstrated a less favorable quality of life relative to the controls at 13 and 26 years. On the other hand, Roberts and colleagues reported that adolescents with a history of extremely preterm or extremely low birth weight have quality of life ratings that are comparable to control peers. Similarly, adults with a history of moderately preterm birth demonstrate a quality of life that is similar to their peers with a history of full-term birth.

The early life experiences of children born preterm, and their families may contribute to cascading consequences in the areas of mental health and neurodevelopment. It is important to recognize that the etiology of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental conditions is often multifactorial, encompassing factors across the social and biological realms. A keen understanding of the key factors and processes that contribute to the differences in development can facilitate the development of interventions that ameliorate the impact of preterm birth and promote child and family well-being. Parental and child health are inextricably linked. In order to support the development of children, clinical attention should also address the needs of parents.

5. Parental Mental Health Outcomes

When considering mental health issues related to preterm birth, it is important to take into account the impact on parents. For many parents, an infant’s admission to the NICU can evoke feelings of shock, guilt, fear, sadness, and helplessness. In summarizing the NICU parent experience, Miles categorized stressors for NICU parents into four categories: (1) the infant’s appearance and behaviors, (2) the sights and sounds in the NICU, (3) parental relationship and communication with staff, and (4) parental role alteration. NICU parents are faced with seeing their sick infant exposed to intensive medical intervention in an unfamiliar environment, while simultaneously learning how to effectively communicate with staff, and to trust in one’s own abilities as a parent. If unaddressed, the mental health sequelae of these stressors can disrupt a parent’s ability to be present and engaged in their infant’s care, potentially causing a negative impact on both the short-term and long-term child-parent relationship, child developmental outcomes, and overall parent mental health.

5.1. Grief and Loss

Experiences of grief and loss are also commonly reported by NICU parents. For NICU parents, the time around the end of their infant’s life can be especially challenging due to issues related to decision making, saying goodbye to their infant, and making preparations for after the death. In addition, NICU parents have reported experiencing anticipatory grief, or the psychological challenges associated with hoping for the infant’s survival while simultaneously preparing for their death. Ambiguous loss is also commonly reported by NICU parents, including feelings of loss related to important milestones or experiences such as the imagined pregnancy or birth, having a baby shower, or being able to hold one’s baby immediately after birth. Additionally, the developmental trajectories of infants in the NICU related to prematurity or other complex medical needs can often be very different than what a parent imagined for their child, themselves, and their family.

5.2. Depression

Despite what can often be a very vulnerable time for all new parents, stressors unique to the NICU experience likely contribute to the higher reported rates of depression among NICU parents when compared to the general population. For example, when compared to the parents of full-term infants, the parents of very premature infants reported much higher rates of depression shortly after birth. Moreover, while approximately one in seven mothers and one in 10 fathers in the general population experience postpartum depression, this number may be as high as four in 10 mothers of preterm infants. With reported feelings of inadequacy, helplessness, and guilt, depressive symptoms have been found in as many as 38% of all NICU parents, often with depressive symptoms decreasing over time.

5.3. Anxiety and Traumatic Stress

In addition to symptoms of depression, parental stressors associated with an infant’s NICU admission have been reported to lead to increased rates of parental anxiety and traumatic stress. Malouf and colleagues found that among NICU parents, 41.9% reported experiencing anxiety, and 39.9% experienced post-traumatic stress. Critical medical diagnoses such as prematurity, traumatic birth experiences, and witnessing infants receive intensive medical intervention can lead to higher rates of anxiety and traumatic stress that may meet criteria for acute stress disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Commonly reported traumatic stress symptoms include symptoms of arousal and intrusion, as well as either a difficulty leaving the infant’s bedside or an avoidance of the NICU. Despite remaining higher than the general population of parents, NICU parent reports of anxiety and traumatic stress have also been found to decrease over time. Lefkowitz and colleagues found that while 35% of mothers and 24% of fathers met the criteria for acute stress disorder a few days after their infant’s NICU admission, when screened 30 days later, 15% of mothers and 8% of fathers went on to meet the criteria for PTSD.

5.4. Substance Use

In the United States, every 25 min a baby is born who will experience symptoms of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) due to the discontinuance of in-utero exposure to substances. Parents of these children are often forced to find ways to cope with their infant’s prolonged NICU admission, as well as with managing their own psychological adjustment and substance use. While little is known about the link between traumatic stress and substance use in NICU parents specifically, the literature suggests that the prevalence of PTSD among those with substance use disorders can range from 25.3% to 49%. In addition to potentially suffering from the biopsychosocial consequences of addiction, a newborn’s withdrawal symptoms and need for intensive and sensitive care can cause a parent distress, guilt, and create challenges for a parent’s ability to bond and connect with their baby.

5.5. Relationship Strain

Parenting a child with a serious or chronic illness increases the risk for breakups or divorce. The relationship strain experienced by NICU parents can be especially challenging because the infant has never left the hospital and parents have yet to experience their baby on their own and may be excluded from care. The differences in coping styles, gender roles and expectations, and communication styles can add additional stress for parents. For example, some fathers are forced to return to work while also feeling responsible for caring for the mother, the newborn baby, and older children. In addition, many NICU hospitalizations can last for months at a time, placing increased strain on the parents to make arrangements for other children and to navigate a return to work, potentially causing parents to be separated from each other for long periods of time. The social and emotional strain placed on NICU parents can persist after discharge and have lasting effects on family relations, including the critical parent-infant relationship and attachment.

6. Parent-Infant Relationship and Attachment

The quality of caregiving relationships during infancy and early childhood has significant and lasting psychological and biological impacts on the developing child. The parent-infant relationship is one of the infant’s most proximal environmental exposures, and preterm infants are considered to be neurologically and biologically more vulnerable to their environmental exposures, hence, it is critical to understand the barriers and challenges in developing optimal relationships in the NICU parents and infants. Prematurity, particularly when leading to a NICU admission, can cause a disruption in the normal process of parent-infant bonding. Preterm infants are less interactive, less alert and, and more easily dysregulated, and as a result their parents can have a harder time reading their cues. NICU admission leads to parent-infant separation and makes it challenging, and at times impossible, for parents to hold their infant and to help soothe or regulate them when in distress. The parents of preterm infants also experience higher rates of psychiatric distress and can experience lower parental self-efficacy (parent’s self confidence in being able to carry out their parental role) which can add to their difficulties in bonding with their infant.

The parent-infant relationship is complex and multidimensional. Maternal sensitivity (defined as the mother’s ability to detect, interpret, and respond to their infant’s emotional and physical needs ), the quality of the parent-infant interactions, and the patterns of attachment are among the main dimensions studied in both the general and the preterm parent-infant population. Sensitive parenting and high-quality parent-infant interactions are associated with better neurocognitive, socioemotional, and language development, and higher academic achievement later in childhood in preterm infants. Inversely, less sensitive parenting has been associated with an increase in externalizing behaviors in early childhood, and in particular, in those preterm infants who experience higher levels of distress in infancy. Drawing on this literature and our general understanding of the effects of the parent-infant relationship in full-term infants, higher levels of parental sensitivity and higher quality of parent-infant interactions are thought to be protective factors in the face of the increased developmental risks that preterm infants face.

Given the importance of high-quality parent-infant relationships in the NICU population and the many challenges these infants and parents face in establishing an optimal bond in the beginning, many researchers have looked at the various aspects of the parent-infant relationship in this population to discern if there are any differences when compared to the general population. The results are heterogenous and difficult to interpret. The heterogeneity in the results is likely due to several factors: (1) as mentioned above, the parent-infant relationship is complex and multidimensional and therefore, different studies have looked at different aspects of this relationship, and even those that have looked at the same dimension, at times, have used different assessment tools and methods, (2) among preterm infants there is a significant diversity in terms of the degree of prematurity, medical comorbidities, and the length of stay in the NICU, all of which can affect the quality of the parent-infant relationship, (3) NICUs and the supportive/therapeutic services they offer (family based developmental care practices, mental health services, psychosocial support services, etc.) differ widely, (4) factors such as race, ethnicity, and psychosocial adversity play an important role in the quality of the care patients receive and in their outcomes, and (5) differences in the study designs in terms of the timeline of assessments, and whether the study is longitudinal vs. cross sectional, and if longitudinal the follow up timelines can all create a heterogeneity in the findings. Here, we summarize some of the findings on the three core dimensions of the preterm parent-infant relationship.

6.1. Preterm Parent-Child Interactions

The majority of the studies that look at the preterm infant behavior have found preterm infants to be less interactive, less responsive, and to demonstrate less positive affect. However, some studies found no differences between the preterm and full-term infant behaviors and a small number of studies found mixed results, or more favorable infant behavior among the preterm infants. It is important to note that the degree of prematurity, other medical comorbidities, pain and distress, or sedation can all impact the degree of a preterm infant’s responsiveness and engagement in dyadic interactions. A larger number of studies have looked at the maternal interactive patterns in the mothers of preterm infants. The findings here are more heterogeneous and therefore, it is not easy to draw any universal conclusions based on these studies. About half the studies have shown less favorable maternal interactive patterns such as lower sensitivity, more controlling and intrusive behavior, and lower responsiveness. There are, however, studies that show higher levels of attunement and maternal sensitivity, and responsiveness in the mothers of preterm infants, and a fair number of studies that have found no statistically significant differences between these mothers and the mothers of full-term infants. Finally, a smaller subset of studies has looked at the quality of the dyadic interaction in the preterm population. About half of these studies have found a lower quality of dyadic interactions in these mothers and infants. These studies have found less dyadic coregulation, less cooperation, synchrony, and positive affect in the preterm mothers and infants. Others have found no statistically significant differences, although the majority of the studies that found no differences were performed when infants were six months or older.

Looking at the findings of the research on preterm parent-infant interaction highlights the fact that preterm mothers and infants constitute a heterogeneous population. There are differences in the infants’ medical condition and birth weight, parents bring their own varying psychosocial and personal backgrounds and histories of trauma or adversity, and the NICUs differ significantly in terms of the resources (including early screening, psychological support, and interventions) that they provide. The timing of assessment can significantly affect the findings: while preterm infants are less interactive and neurologically premature, in many cases they eventually catch up with their full-term counterparts. Similarly, during the early postpartum period and the NICU admission, many parents experience higher degrees of psychological distress and uncertainty about their infant’s developmental and medical outcomes. Therefore, depending on the population studied and considering the variations in methodological designs discussed earlier, it is not surprising to see the heterogeneity in the findings.

Nevertheless, a number of points can be more definitely concluded based on these studies: (1) preterm infants, in particular very preterm and extremely preterm infants and those with medical complications, contribute substantially less to the dyadic interactive flow and use different ways of communicating their needs and distress. This in turn, can affect parental interactive patterns with these infants, (2) there are subsets of vulnerable groups among parents of the preterm infants when it comes to parental sensitivity and interactive style. Some of the factors leading to vulnerability are better known, however, we need to better understand which parental and infant factors can lead to an increased vulnerability in developing optimal parent-infant interactions in the preterm population, and (3) preterm infants and their parents may undergo periods during which the quality of their interactions are more challenged (including during the NICU stay, the immediate period post-discharge, and the times when there are medical crises or complications). These periods of increased vulnerability need to be better studied and understood.

6.2. Preterm Parent-Infant Attachment

Another important framework to assess the parent-infant relationship is through attachment classification. Attachment theory and science describe the role that parents play for their infants in making them feel safe, secure, and protected. Children who consistently receive sensitive, loving, and responsive parenting are able to use their parents as a safe haven when feeling in danger and a secure base from which to explore their environment. These children develop what is classified as a secure attachment. Unlike children who develop secure attachment, those who develop insecure attachment often are faced with inconsistent or distant, insensitive, or unresponsive caregiving. Broadly, the insecurely attached children are divided into the anxious-ambivalent group (children who have received an inconsistent quality of responsiveness and sensitivity and therefore act in ambivalent ways toward their caregivers) and the anxious-avoidant group (children who have received an insensitive, unresponsive, and absent caregiving who are unable to use their caregiver as a safe haven or a secure base). A fourth category of disorganized attachment was later added to this classification. Children who have disorganized attachment style often have caregivers who are at times frightening or frightened due to their own significant history of unresolved trauma. These children do not have an identifiable pattern of relating to their caregivers at times of separation, reunion, or distress. Even though a disorganized attachment is the only category that is directly associated with later psychopathology, insecure attachment styles are also associated with problematic patterns of emotional regulation, interpersonal, and academic skills. The gold standard for the assessment of attachment style is the Strange Situation Protocol (SSP) which is often used when the infant is nine to 18 months old.

Many of the studies that have looked at the preterm infant’s attachment styles have reported higher rates of insecure attachment in this group compared to the full-term infants. Studies have also found higher rates of disorganized attachment. However, these findings are not consistent, and some research has not demonstrated any statistically significant difference in the rates of the various categories of attachment styles between the preterm and full-term infants and their caregivers. Looking more closely at some studies, there are again subpopulations of preterm infants who might be at a higher risk of developing insecure or disorganized attachment styles: VLBW infants, infants with respiratory illness, those with longer lengths of hospitalization, and children with more significant developmental delays. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the infant, parental, and environmental factors that can impede or promote the child’s attachment to their caregiver. Identifying the infants and parents who are biologically, medically, developmentally, or psychologically at risk of developing insecure or disorganized attachment styles can help us tailor interventions and support systems specific to their needs.

7. Impact on Parenting

In addition to the impact of preterm birth on the attachment and parent-child interactions, it is important to consider how these early life experiences for both parent and child affect parenting behaviors. Parents have a critical impact on an infant’s learning and development through parenting interactions. Parental emotional trauma during a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission often has a significant impact on the parents’ mental health and distorted parental perceptions of their child’s vulnerability (PPCV). This impacts their parenting styles and can result in a style of overprotective parenting. NICU parents are at a high risk for developing increased PPCV. Parents of preterm infants had significantly higher PPCV for their healthy children at age 36–42 months old compared to healthy term infants. Sixty four percent of the mothers of ex-premature infants viewed their children as vulnerable in one study. Additionally, about 83% of mothers who experienced significant emotional trauma during the NICU stay also say they have distorted vulnerability views of their infants. It has been found that the medical complexity of the infants does not correspond with the PPCV ratings, and that NICU parents have high ratings of PPCV compared to healthy term infants.

The effects of increased PPCV on the parents and child can persist after the infant’s discharge from the NICU, such as compromises in optimal parenting skills and stunted learning and developmental outcomes for the child. This is described in the concept of Vulnerable Child Syndrome (VCS). Green et al. first described the theory that VCS affected parents with children whose ages and diagnoses varied, but that a fear for the child’s survival persisted even after the resolution of a traumatic health event. This fear led to increased PPCV and then overprotective parenting skills. The final common point was associated poor outcomes for the child’s behavior, social skills, over somatization of bodily symptoms, school problems, health care utilization, and psychological problems. In 2015, Horwitz et al. developed a theoretical model specifically for VCS in NICU children and showed that the maternal responses and sequelae to traumatic events, maternal dysfunctional coping methods to trauma, and the levels of family support were most influential in the development of VCS, per a multi-regression analysis model. Hoge et al. have further explored the concept of utilizing trauma-informed cognitive behavioral therapy models to predict the risk and progression of the development of VCS.

The reported incidence of VCS in the general pediatrics literature has been around 10–21%; however, the incidence in the NICU families is unknown. Given that the risk factors of anxiety, depression, trauma, and distorted views of vulnerability are high in this population, more so than the general population, it could be assumed that the incidence is at least as high as in the general population, and likely higher. Thus, it is important to support the NICU parents during the infant’s hospital stay by finding ways to ameliorate their ability to effectively cope with the emotional trauma during, and after a NICU admission, and help them have realistic and healthy perceptions of their child for the future.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) could be an effective mode of treatment to prevent VCS in the NICU population. Manualized CBT has been shown to be feasible to address concepts of PPCV and VCS in the NICU parents of premature infants with very high parental satisfaction. These parents have expressed stories of utilizing the techniques and improving situations once discharged from the NICU. Ongoing analysis is underway to assess the effects on PPCV scores and long-term outcomes of the children.

8. Discussion

With increased rates of survival of preterm infants, attention is now being focused on the long-term issues affecting both infants and their caregivers. These include not only chronic medical complications and neurodevelopmental delays, but also the parenting and mental health issues that have been referenced above. For many parents, the trauma of a preterm birth may have a lifelong impact, not only on styles of attachment and parenting approaches, but also on their own mental health and well-being.

Interest in these issues has led to the growth of new specialties, including neonatal mental health and developmental care. While still a relatively young field, it is fortunate that researchers are starting to develop a number of effective and evidence-based interventions that have the potential to improve both the infant and parent outcomes. These include: (1) developmental care interventions involving measures to reduce infant pain and stress, sensory interventions to stimulate development, and educational interventions that teach parents how to recognize their infant’s developmental needs and foster healthy parenting skills, (2) interventions that include parent-infant psychotherapy that address the relationship and interactions between the parent and infant with the goal of fostering parental sensitivity and engagement, and (3) interventions directed specifically at the parents to address parental stress and trauma.

Although these interventions have proven efficacy and long-term benefits, access to psychological and developmental care services is not uniform across the NICUs. Even in those hospitals that fund psychological services, there are often gaps and disparities in their implementation and utilization based on cultural and systemic variables. In part, these gaps exist due to the absence of robust mental health screening for parents. Although many obstetrical programs now offer screening for depression, it is rare for the NICUs to routinely screen parents of preterm infants, in particular, the non-birth parents who may be equally impacted by the birth trauma. In addition, access to follow-up mental health care after the infants are discharged is often variable and, in many cases, completely absent. Similarly, preventative mental health care in the prenatal period is generally not available even in well-funded academic programs.

Looking forward, there is a strong need for research and program development in the areas of neonatal mental health and developmental care. Although there is some data that has shown shorter lengths of stay and decreased health care costs, there has been no systematic evaluation of the risks associated with not offering early intervention or the potential benefits of providing these services. Patterns of overprotective parenting and symptoms of VCS, for example, as described above, have been linked with the overutilization of healthcare services in pediatric care, as well as increased rates of somatization, which also burden the healthcare system. However, without robust evidence to demonstrate the financial benefits of early childhood and parent interventions, it will be difficult to convince both hospital programs and insurance companies to provide adequate mental health care and parent support. Future research would do well to demonstrate the benefits of mental health and developmental care interventions for the well-being of infants, families, and the health care systems that serve them.

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/10/9/1565

Gravens By Design: “Hands-Off” and “Hands-On” Care in the NICU: Can They Coexist and be Mutually Reinforcing in the NICU of the Future?

Robert White, MD

In this decade, we have witnessed the steady growth of both “hands-off” and “hands-on” care in the NICU. While at first glance, these would seem to be competing concepts—and indeed, they have been in many respects in the early part of this decade. Experience with both concepts has grown, and now a new factor has emerged—artificial intelligence (AI), which may help us find a way to realize the benefits of both strategies while avoiding most of their downsides.

I will define “hands-off” care as the intent to avoid stress in high risk newborns whenever possible by limiting any “unnecessary” (a concept mostly in the eye of the beholder since there is a paucity of data available to define this) sensory input, to include not only touch but also visual and auditory stimuli. This concept was born out of an era in the early days of NICU care when infants were subjected to excessive stimuli of all sorts—except for human contact, which was extremely restricted.

I will define “hands-on” care as the effort to keep babies in the arms of a parent or surrogate as much as possible, even very soon after birth and even if receiving intensive care in the form of endotracheal intubation, umbilical vessel catheterization, and other similar invasive measures. This, too, can be seen as a reaction to the minimal access given to parents in the early days of NICU care but obviously with a much different philosophy to the “hands-off” approach. Both strategies are intended to minimize the stress on the newborn so they can thrive, but through entirely different methods.

Both “hands-off” and “hands-on” care have advocates who have produced strong scientific evidence that their approach has led to better outcomes than in previous eras. Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) prevention protocols embrace a number of “hands-off” practices and, when bundled together, have been shown to reduce the incidence of IVH. (1) However, there is little evidence that any individual component of the bundle (such as minimal touch or continuous dim lighting) is essential to the success of the bundle. In many NICUs, most components of these bundles are continued well beyond the time frame used in the studies to show benefits for IVH prevention; in particular, infants on ventilatory assistance are often kept on “minimal stress” precautions for weeks or months. Notably, one characteristic of these protocols, formal or informal, depending on the NICU, is that parents are given limited opportunities to hold their babies while they are on ventilatory assistance.

On the other hand, proponents of “zero separation” have shown that even the highest-risk infants can be safely held by their parents and exposed to various auditory and visual stimuli in the first days of life, with outcomes comparable to the most cautious NICU protocols. (2) A third trend has emerged, that of AI, although it has yet to have practical applications in the NICU with respect to these challenges. Can we project how each of these well-intentioned strategies might play out in the coming two or three decades (the typical lifespan of a NICU), so that someone currently planning a new NICU will create an environment of care that gives its babies, families, and caregivers the maximal benefit of all of these trends? Let us start with basic goals, which I suggest can be identified as follows:

• Support infant homeostasis to the greatest degree possible in order to optimize growth, development, and healing.

• Optimize parent-infant interaction to the greatest degree possible.

• Provide caregivers with as much information as possible to guide their care, packaged and processed, to maximize the accuracy and thoroughness of medical decision-making.

In today’s NICU, “hands-off” and hands-on” strategies are intended to support homeostasis, thereby minimizing stress and its related complications, although they seek to achieve that goal through very different methods. Could AI help here? Perhaps so— one of AI’s most obvious uses would be detecting imperceptible changes and trends in a patient’s status and either alerting a caregiver or implementing a change in clinical support according to the given directions. Consider, for example, our current method of adjusting ventilatory support for a very preterm infant in the first days of life. In the first era of neonatology, we adjusted oxygen input based on visual assessment of color and frequent arterial blood gases; we adjusted ventilator settings based on those same blood gases and ancillary tests such as chest X-rays. With the advent of transcutaneous O2 saturation and pCO2 monitors, we obtained real-time continuous data, occasionally confirmed with much less frequent blood gases, but usually could make adjustments in oxygen concentration and ventilator settings based on the transcutaneous information. It is only a matter of time before AI can receive that same information as well as data from the ventilator itself and, based on parameters determined by the clinician, make adjustments in ventilator settings continuously, still with intermittent adjustments in either actual settings or the parameters being used by AI by clinicians as they see fit.

One can imagine a similar strategy being employed to manage continuous drips to support blood pressure or blood glucose. It is perhaps a little more of a stretch to imagine how sensory input could also be managed with the help of AI. However, let us agree that the goal should be to minimize noxious stimuli and maximize nurturing stimuli. We must only identify how we judge an infant’s response to a given environmental input to determine whether it should be limited or encouraged. It is very likely that we already have access to continuous data, such as heart rate, cerebral oxygenation, and brain wave activity, which can be used for this purpose once we learn how to train an AI helper properly.

If AI could provide directed, automatic intervention as well as alert clinicians to times when an infant needed more direct attention, it should be possible to put an infant in the arms of his/her parents with the assurance that homeostasis would be maintained or the clinician alerted when that was not possible within the parameters selected. In this future, but perhaps not too distant scenario, babies could be safely in the arms of a parent or surrogate most of the time.

What impact would this next era of care have on NICU design? First —and we are probably already there—NICUs will not need to be constructed with “line of sight” considerations in which nurses would have direct visibility of their baby’s bed. All the information once gained by this design consideration is now available through the interlinking of monitors, cameras, and personal communication devices. This does not mean that nurses will not have direct contact with their patients; their bedside duties will remain, but when they are away from the bedside, they will still receive all the information they need about their patient’s status electronically. Second, it is likely that we can customize each infant’s immediate environment—lighting, auditory, temperature, humidity, etc.—to their specific need, rather than using a “one size fits all” approach that we have been forced to use until now. Third, if we can safely provide care to babies while they are being held for extended periods, we can design our NICUs in a way that fully supports a parent or parents who want to essentially live with their baby during the NICU stay, and therefore create patient rooms and support spaces that welcome families as an integral part of our care team, rather than as visitors.

It will be a brave new world, but babies will get even better care while minimizing stressors for caregivers and families. The NICUs that do this best will be designed with these changes in mind.

https://neonatologytoday.net/newsletters/nt-jan24.pdf

PREEMIE FAMILY PARTNERS

Perspectives on Parenting in the NICU Advocacy, Support, and Partnership

Barnes, Jessica MSN, RN, RNC-NIC, NPD-BC; Vance, Ashlee J. PhD, MA, RN, RNC-NIC

Advances in Neonatal Care 24(1):p 1-3, February 024. | DOI: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000001144

Supporting parenting in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is one of the most challenging but rewarding aspects of patient care in neonatal nursing. As nurses, we are uniquely positioned to offer support, advice, and guidance in the transition to parenthood. Yet, sometimes parents perceive us as “gatekeepers” to their newborn rather than facilitators of access. As the neonatal nursing community works to improve care for all patients, parenting in the NICU is one element of care that needs to remain at the forefront. Consider the following experience of a parent, who has been on “both sides” of the incubator as a NICU nurse and then a NICU parent.

OUR STORY

After 12 years working in high-risk perinatal care and level III NICUs, I found myself on the other side of the bed, watching my child received the same care I had provided countless times to other babies and their families. Instead of guiding a parent through one of the most challenging and difficult experiences of their lives, I was the one now in need of support and guidance. My daughter, Aurelia, was born in August 2022 at 27 weeks 5 days of gestation, after a placental abruption, which began at home. On the night Aurelia was born, I woke up to a significant amount of blood that quickly increased. I immediately sensed what was happening. As my husband was speeding to the hospital through overnight construction traffic, I was acutely aware of what laid before us. If we both survived, our whole family was facing months of uncertainty, anxiety, and separation. I wept for my baby, myself, my husband, and my 2 other children at home. How were we going to do this?

I delivered Aurelia at the hospital where I worked for 10 years—with much of that time spent in their large, high-acuity level III NICU. Although I was no longer working in that unit, I called the NICU charge nurse from the L&D waiting room and explained our situation. Even though she did not know who I was, I told her to prepare for a STAT 27-weeker and I needed to know which provider was on call. She cautiously gave me details about the delivery team and assured me they were getting a space ready for my baby.

The nurse in labor and delivery triage kept telling me everything was going to be okay while trying to find Aurelia’s heart tones. After the third time, I asked her to stop saying it was okay. I knew this was a preterm abruption and nothing about this situation was okay. I needed to hear my baby’s heartbeat and get to the OR as quickly as possible. I needed to know she was still alive, and we both needed to be saved. I thought of my 2 boys at home and wanted so badly to be able to see them again. I wanted my baby to survive despite all the potential challenges ahead of her.

OUR PRIVILEGE

I want to pause here and take a moment to acknowledge the immense privilege I carried with me into our NICU stay. Not only did I have experience and knowledge of the NICU environment and the medical care necessary for my baby’s survival, but my positionality as a White woman with adequate employment and good insurance. We had a good support network providing childcare so that my husband and I could be in the NICU daily. Additionally, I had already established care with a therapist, who was also a NICU parent, as we embarked on our own NICU journey. I had so many moments sitting at Aurelia’s bedside thinking about my struggles and wondering if I was struggling this much, despite my privilege, how much more challenging it must be for other families. If it’s this hard for me, I can’t imagine how other families did it.

During the first few days of our hospitalization, I tried to be “easy” parent. Because of my experience, I knew we had a long stay ahead of us, and I didn’t want to develop a reputation. I accommodated the nurses, thought of their tasks and schedules before my own, and felt the constant tension of wanting to interject when it wasn’t the way I would have done it. This all changed for me after Aurelia’s first bath.

I coordinated with the nurse to be present for Aurelia’s first bath at 3 am on her fourth day of life while I was still inpatient. That night, I fell deep asleep for the first time since she was born, and I woke up in a panic at 03:09, knowing immediately that I might have missed my window. I rushed to the NICU as quickly as I possibly could, considering my postpartum, postoperative recovery. I arrived at her bed at 03:14 to her nurse putting away the plastic bath basin. She turned to me and said, “We said three o’clock.” Those 4 words completely shattered me, and I felt an intense wave of grief flood me. I sat down at her bedside and cried the hardest I had ever cried in my life. It was in this moment that I realized being the “good parent” or “easy parent” was not meeting my needs nor my daughter’s. Aurelia may have been taken out of my body, but here in the NICU, I felt like she was not mine. I was at the mercy of the nurses, doctors, respiratory therapists, and countless other people overseeing her care. I was outnumbered and terrified; all my previous experience did not prepare me for this moment.

IMPORTANCE OF PRESENCE

Missing Aurelia’s first bath put everything into perspective for me. I was/am her mother; that’s who she needed me to be, her advocate. I would do whatever it took to be heard and supported. One of the most frustrating experiences during her NICU stay was the constant reminder to “just be her mom right now.” When I heard comments like this, what I understood the team to be saying was, “Don’t ask too many questions. Just sit quietly. I’ll let you know when you can interact with her.”

The irony is that while they were telling me to be her mother, there were more moments when the opportunity to be her mother was not possible or taken from me. It is a mother’s job to bathe, hold, feed, and care for her infant, but in the NICU, those activities often require permission: to be given permission from the “gatekeepers.” The conflict between my personal and professional understanding of the situation further complicated my traumatic experiences. I knew as a professional that there were legitimate reasons for some of the responses I was given, but as a mother, there was nothing any of the nurses could say that I would find acceptable. I was trying to be her mother, yet it was so hard! There were so many competing interests: how do I integrate my knowledge as a mother and my experience as a nurse?

So, I decided to be myself and lean into the duality of my role as Aurelia’s mom and as a NICU professional. I was authentic and honest with the team. I started with transparent communication despite it being perceived as negative. Some offered a sympathetic ear and a shoulder to cry on, others seemed to take it personally and tried to appeal to my sense of “knowing better.” When offered unsolicited advice, I would remind them that my experience was unique and valid. The times that I felt the most supported as her mother were when I was able to express my authentic emotions about what was happening—the everchanging mixture of pride, fear, love, anger, and gratitude I felt at any given moment. A few colleagues were consistent sources of support. They provided meals, acknowledged the disappointment, stress, and grief we were experiencing while also celebrating every weight gain, skin-to-skin session, and successful eating experience. I will forever be grateful for their kindness and support.

IMPORTANCE OF PARENTING AND PRESENCE

Parental–infant separation is inherently traumatic. Human beings are social beings that need human connection to thrive and so the effect of being separated from and not able to hold your baby after birth is a common source of trauma reported by former NICU parents, which also increases their risk for developing posttraumatic stress disorder. When an emergency and the need for life-saving care disrupts the bonding process, the sequela of events that follow can negatively impact parents and infants. Postpartum Support International lists NICU admission as an example of trauma and risk for developing postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder (P-PTSD). Symptoms include “intrusive re-experiencing of a past traumatic event… flashbacks or nightmares, avoidance of stimuli associated with the event … persistent increased arousal (irritability, difficulty sleeping, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response), anxiety and panic attacks, feeling a sense of unreality and detachment.” The American Psychiatric Association estimates 17% of parents experience P-PTSD or birth-related trauma—a number that only includes those who meet clinical criteria for diagnosis as many more parents experience P-PTSD symptoms.4 But what many former NICU parents will tell you, is that even after leaving the NICU, the NICU never really leaves you. NICU parents remain at risk for developing P-PTSD up to a year after their infant’s discharge. Every noticeable difference from your baby gets mentally tagged and then the worry sets in wondering if it was connected to their birth. Is this her normal or is it because she was born early or in the NICU? These lingering questions make it even harder to process the trauma exposure from the NICU. I have always been a strong advocate of trauma-informed care (TIC) and have integrated TIC principles into every class I teach as a neonatal clinical nurse educator. I remember telling my therapist during one of our virtual sessions, as I sat in my car in between care times, that I felt like I was disassociating—like I was watching a movie about the NICU as if it was happening to some other family. Again, all my professional experience and training couldn’t have possibly prepared me for this traumatic experience, even though I knew what to expect from the environment. Even the most clinically benign NICU admission can be traumatic, and processing that trauma takes time.

During our NICU journey, I experienced the effects of toxic positivity, which I had not recognized before. Toxic positivity is defined as “dismissing negative emotions and responding to distress with false reassurances rather than empathy.”6 When people are uncomfortable or are unsure of what to say, they often rely on vague or empty statements. The team kept telling me over and over to “be grateful,” “this will all be over soon,” or “at least she’s growing/doing well/not requiring a lot of respiratory support.” My reaction to these comments highlighted how dismissive they were and reminded me of all the times I said similar things to other parents. For example, during her first and only septic workup, I was told “Hey! It’s her first one. It’s not a NICU stay without a workup or two. I’m surprised it hasn’t happened already” and while I understood this sentiment as a professional, as a parent, it shattered my emotional composure. It was one of our worst days in the NICU, and these comments did nothing to validate or acknowledge the worry and fear we were feeling.

In short, I learned language matters. If nothing else changes in your clinical practice after reading this or other articles, other than removing the phrase “at least” in your communication with parents, then that will be a win for me. Even though I was deeply grateful that this was only her first workup and that she was getting the right care at the right time, I was still upset about the pain my daughter was feeling and concerned about implications of the results. Multiple things can be true at once: parents can be grateful, disappointed, scared, and angry at the same time. Statements that are dismissive of parents’ emotions and concerns can further exacerbate their traumatic experience and distrust of providers. Given the focus of individualizing care for infants, we must also acknowledge and individualize the emotional support provided to parents and not be dismissive of their experience.

VALIDATION AND EMOTIONAL SUPPORT

In healthcare, we often focus on the short-term outcomes. Nowhere is that truer than the NICU. We celebrate every discharge and pat ourselves on the back for a job well done of getting a baby home. We reminisce about former patients and enjoy seeing holiday cards and getting updates at return visits or reunions, but so much more could be done to connect us with the lived experiences of our patients and their families as they navigate the transition to parenthood in an unfamiliar environment. The care we provide today potentially impacts every one of their tomorrows. Why wouldn’t we want to support their family’s transition to home in the best way possible? In sum, Aurelia’s 75-day stay in the NICU was clinically uneventful. I owe that in part to the high-quality care she received, but I also believe our consistent presence in the NICU as her parents played a protective role in her outcomes. Validation fosters resilience and resilience mitigates the impact of trauma. My hope in sharing my experience is to empower more NICU professionals to choose to foster resilience in our patients and their families.

We hope that this special series, Parenting in the NICU, offers new insights, challenges conventional practices in the NICU, and sparks a desire to promote care that values and validates the parent’s role in the care of their child during a NICU hospitalization. Let’s meet parents where they are at, knowing the lasting impacts our choices have on their transition to parenthood.

2024 NCH NICU Reunion

NCH·Feb 1, 2024

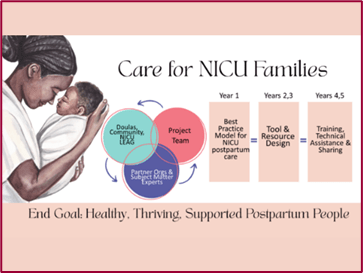

New Funding Supports “Care for NICU Families” Research and Program

October 26, 2023

Interdisciplinary Collaborative Receives $4 Million Cooperative Agreement from the CDC to Improve Postpartum Care In and Beyond the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Chapel Hill, NC, October 2023 – The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Department of Pediatrics and Collaborative for Maternal and Infant Health, along with Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere, the University of California San Francisco’s School of Nursing and subject matter collaborative partners, have received a $4 million Cooperative Agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to Advance Best Practices to Improve Postpartum Care In and Beyond the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (“Care for NICU Families”).

Collaborative partners include Mighty Little Giants, Breast Friends Lactation and Support Services, the 4th Trimester Project, Bellamy Management Consultants, Narrative Nation, the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality, the National Perinatal Association, Postpartum Support International, the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, Sabia Wade, and Heather Burris.

Care for NICU Families

The team will build a national partnership guided by community and diverse lived experience voices to develop a set of Best Practices for Postpartum NICU Care along with co-created tools and strategies to support model care. They will share what they learn across NICUs, professional and community networks nationwide, and provide technical assistance to groups who are ready to make change. This will lead to increased awareness and use of effective data-informed clinical care and public health resources and interventions, as well as increased capacity to implement clinical and public health approaches to improve outcomes for postpartum people.

Co-Principal Investigator (Co-PI) Dr. Ifeyinwa Asiodu highlights that “The long-term goal of this important project is to eliminate perinatal health disparities and improve postpartum health and wellbeing during NICU stays through the transition to home. Continuity of care, including addressing the physical and mental health needs of the postpartum person and family, is critical to improving care for NICU families.“

The United States has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality and morbidity among wealthy countries (32.9 deaths per 100,000 birth) with unacceptable inequities due to historic and structural racism: Black birthing people experience a rate of maternal mortality 2.6 times higher than those who are White. “We know from previous research that mothers with infants in a NICU are more likely to have experienced a birth-related trauma, have depression/anxiety, lack access to basic care, have a chronic health condition, experienced a cesarean birth, and/or a blood transfusion, than mothers whose infants do not have a NICU stay,” Co-PI Dr. Sarah Verbiest underscored. Dr. Verbiest also directs the Jordan Institute for Families at the UNC School of Social Work which focuses on building economic and social supports for families with young children.