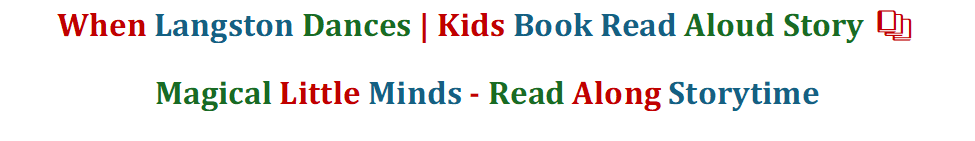

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast. It is part of the Southern Cone region of South America. Uruguay covers an area of approximately 176,215 square kilometers (68,037 sq mi). It has a population of almost 3.5 million people, of whom nearly 2 million live in the metropolitan area of its capital and largest city, Montevideo.

Uruguay is highly ranked in international measurements of democracy, government transparency, economic freedom, social progress, income equality, per capita income, innovation, and infrastructure. It is classified as a high-income economy and has fully legalized cannabis—the first country in the world to do so—as well as same-sex marriage, abortion and euthanasia. Uruguay is also a founding member of the United Nations, the OAS, and Mercosur.

The current Uruguayan healthcare system is the State Health Services Administration (ASSE) created in 1987. The National Healthcare Fund (FONASA) is the financial entity responsible for collecting, managing and distributing the money that the state has destined for health in the country. It was created in 2007 to entitle all employees and pensioners to health care outside of the public health system. Latest government figures state that there are 2.5 million people registered with Fonasa – out of a total population of just over 3 million. This would mean that 500,000 Uruguayans are left choosing between the public system or having to pay the full amount for private health care.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uruguay

- GLOBAL PRETERM BIRTH RATES – URUGUAY

- Estimated # of preterm births: 8 per 100 live births

- (Global Average: 10.6)

- Source- WHO Preterm Birth Rate (Per 100 Live Births)

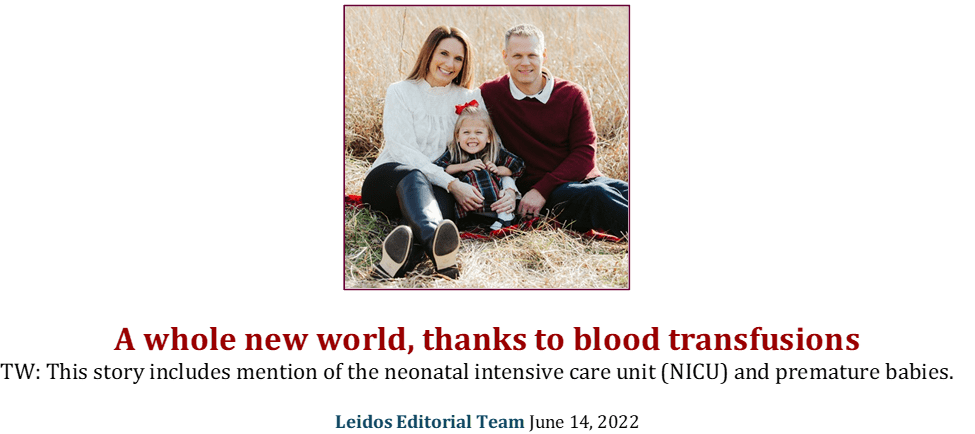

COMMUNITY

Much has been written about medical errors that reach patients. Almost without exception, these accounts focus on tragic outcomes, cases in which patients suffer harm or die as a result of mistakes in diagnosis, treatment, or communication. Entire fields of research, safety initiatives, reporting systems, and regulatory frameworks have been developed in response. By framing medical error as a systems problem rather than an individual failing, health care has sought to encourage transparency, promote reporting, and ultimately reduce preventable harm. This approach is necessary, ethical, and long overdue.

Nevertheless, another category of medical error receives little attention in the literature or in public discourse. It is an uncomfortable and largely unspoken phenomenon: errors that reach patients and, paradoxically, improve their clinical course.

These events are rarely documented, formally reported, or analyzed. They tend to live in the realm of anecdote, shared quietly in hallways or over coffee, often accompanied by discomfort or nervous humor. A test ordered on the wrong patient reveals a life-threatening condition that would otherwise have gone undetected. An unintended medication change exposes a diagnosis sooner than expected. A deviation from standard practice uncovers a better therapeutic pathway. There is no research into these “random” improvements. These occurrences are typically dismissed as luck, coincidence, or, for some, providence.

Occasionally, they are more than that. Medical history itself is replete with discoveries born of accident. Penicillin was not discovered through a carefully designed protocol but through contamination. Countless diagnostic insights have emerged from unexpected findings. While these events do not excuse error, they complicate the narrative that all deviations from protocol are uniformly harmful.

This raises an unsettling question: Is all medical error inherently detrimental to patient care?

From the standpoint of risk management and patient safety, the answer must be yes. No health care institution would, or should, endorse error as a tool for discovery. Indeed, no clinician has ever been sued for failing to make a mistake, although many have been sued for making one. The legal, ethical, and professional imperatives are clear. Errors must be minimized, reported, and prevented.

However, the practice of medicine is not merely the execution of flawless protocols. It is a human endeavor, characterized by uncertainty, variation, and judgment, which some would call the “practice” of medicine. If medical care were delivered without any deviation, without experimentation, adaptation, or learning from the unexpected, would we consider that the “perfection” of medicine, or its stagnation?

Consider the randomized clinical trial, the “gold” standard of medical evidence. By design, half of the participants receive a therapy that ultimately proves inferior. When the superior arm emerges, we do not label the inferior treatment a medical error, nor do we report it to risk management. Instead, we publish the findings, celebrate the advance, and change practice accordingly. Progress is achieved precisely because uncertainty was permitted within ethical boundaries.

Honestly, though, the best path may not be through completing the trial but through interim analysis or using alternative research strategies such as “play the winner.” In seeking strategies that optimize good science rather than patient outcomes, we may find ourselves stuck promulgating only treatment modalities that have been completed and accepted for publication. Moreover, negative studies are usually not accepted for publication. In this context, error and expertise begin to blur. What is considered a mistake today may, in retrospect, be recognized as the first step toward tomorrow’s innovation. This does not absolve clinicians or systems of responsibility, nor does it diminish the real harm caused by preventable errors. (1, 2) Instead, it challenges us to acknowledge that medicine advances not only through precision but also through humility, recognizing that our current standards are provisional and that learning often emerges from imperfection.

The task, then, is not to romanticize error, but to understand it more honestly. Error, like medical expertise, may ultimately lie in the eye of the beholder. What is labeled a mistake in one era may later be understood as the necessary precursor to discovery, refinement, or progress. This reality does not weaken the moral obligation to protect patients from harm, nor does it excuse preventable failures in care. Instead, it underscores the complexity of practicing medicine in a world of uncertainty, evolving evidence, and imperfect knowledge.

The challenge for modern medicine is to uphold the highest standards of safety and accountability while preserving the intellectual flexibility that allows clinicians and scientists to question assumptions, recognize unexpected patterns, and learn from outcomes that diverge from expectations. Only by balancing vigilance with curiosity can the field continue to evolve in ways that serve both current patients and future generations.

Source: https://www.neonatologytoday.net/newsletters/nt-dec25.pdf

Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of an mHealth neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) parent support smartphone application to improve psychosocial well-being, specifically reduced stress and anxiety, increased parenting competence, and improved social support among a diverse group of parents with infants born preterm in 3 Chicago-area NICUs.

Study design

A time-lapsed, quasiexperimental design in which control participants were enrolled and then intervention participants enrolled. Data collection occurred at 3 timepoints: NICU admission (AD), discharge (DC), and 30 days post-DC (DC+30). Validated outcome measures included parenting sense of competence, stress, anxiety, and social support.

Results

Intention-to-treat analyses included 400 participants (156 intervention; 244 control). After covariate adjustment, a significant increase in parenting sense of competence (AD–DC, DC+30), decrease in stress (AD–DC+30), decrease in anxiety (AD–DC, DC+30), and increase in social support (AD–DC) were noted but did not differ by study arm. However, secondary analysis of parents with infants born at <32 weeks of gestational age (156 participants) showed decrease in stress (AD–DC+30) that was greater in intervention vs control group (P = .03). Among intervention participants who were Black, a significant increase in social support (AD–DC) total score (P = .01), and 2 subscales of emotional/informational support (P = .02) and positive social interaction (P = .02) were found.

Conclusions

This novel mHealth intervention shows evidence of reduced stress and anxiety while increasing social support among some subsets of parents at high risk of negative psychosocial experiences in the NICU, potentially enhancing outcomes for infants born preterm by ensuring that parents are less stressed and better supported.

Source:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39880156/

Background: The need for paternal support is rarely addressed in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Neonatal nurses often primarily focus on the needs of the mother and infant and may not be trained in support of fathers.

Purpose: To investigate nurses’ self-efficacy (SE) in guiding and supporting fathers after implementing a father-friendly NICU.

Methods: Nurses from the intervention NICU and 13 control NICUs were included in a before-and-after intervention study. Questionnaires measuring nurses’ SE regarding support of fathers and mothers were obtained when starting the development process, before and 18 months after the implementation. The primary outcome was the difference between nurses’ SE scores for father and mother questions in the intervention group compared with the control group.

Results: In total, 294, 330, and 288 nurses responded to the first, second, and third questionnaires, respectively. From the first to third questionnaires, the intervention group showed a significantly higher increase in SE scores for father questions compared with the control group (0.53 vs 0.20, P = .005) and a nonsignificantly higher increase for mother questions (0.30 vs 0.09, P = .13). In the third questionnaire, the intervention group showed a higher SE score for father questions compared with the control group (9.02 vs 8.45, P = .002) and the first questionnaire (9.02 vs 8.49, P = .02).

Implications for practice and research: By implementing a father-friendly NICU, nurses’ SE for providing support to fathers increased significantly. Training in a father-friendly approach increases nurses’ ability to support both parents. Copyright © 2023 The Authors. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses.

Source: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37463518/

Every situation is different, every mother and every family are different, and what ‘works’ for some parents may not work for others. Don’t pre-judge or assume. No one can be prescriptive about what to say or do, but here were some phrases and behaviors we heard about that were typically either helpful or not helpful.

Phrases that were un-helpful

- At least you still have one

- You can try again (for another pregnancy)

- It wasn’t meant to be

- Maybe you weren’t ready; maybe [twin’s name] wasn’t ready

- Why don’t you stop thinking about or forget about [twin’s name] and just focus on the other twin?

- You’ll get over it

- You’ll soon get over it

- I know what you going through (unless of course, you have been in a very similar situation)

- You need to talk about it (this is very different to saying ‘would you like to talk about it’ or ‘do you want to tell me when it would help to talk’)

Behaviors that weren’t helpful

- Not talking about the twin because you are worried about upsetting the parents

- Not calling the twin by their name (if they had one) or forgetting their name

- Not recognizing the twin identity (trying to behave as if it was a singleton pregnancy)

- Staying away, not ringing or messaging, because you felt uncomfortable (any discomfort you feel is insignificant compared to the parents’ grief)

- Trying to focus on, or just talk about, the surviving baby or babies

- Where a triplet dies, suggesting that the two surviving babies are ‘only twins’ (although some parents told us they wanted to think of the surviving babies as twins, typically where the triplet loss was quite early in pregnancy). If you are not sure, ask the parents.

- Not saying anything because you don’t know what to say (sometimes saying ‘I am really sorry, I don’t know what to say’ is enough)

- Discarding any mementos from the baby who died – photos, cot cards, name tags, blankets & clothes (however dirty, do NOT wash them without asking parents), items bought for the baby before they were born e.g. clothes

Phrases that were often helpful

- I’m really sorry, do you want to talk about it?

- I’m sorry

- Do you want to tell me when it would help you to talk about her or him? (even better to use the baby’s name)

- Is there anything I can do to help?

Behaviors that were often helpful

- Talking about the twin by name

- Asking if you can say hello and goodbye to the baby who died

- Helping make memories, collect mementos

- Taking and keeping photos (with parents permission)

- Offering to help with ‘household’ chores – parents of babies on NICU struggle to do routine tasks – walk the dog, go shopping etc. However, be careful not to ‘smother’ families or remove their family identity/role

- Offering to help with other siblings

- Offering to tell other family members or friends what has happened. However, always ask parents first what they would like.

The grief and sadness that parents feel will stay with them for months and years, often their whole life. Offering to talk months or years later about their grief, or talking about the baby who died by name is appreciated by most parents. If they are a close friend, or family, and you do not know what they would like, ask them!

Source: https://www.neonatalbutterflyproject.org/resources/

HEALTHCARE PARTNERS

My name is Marília Rêgo, and I’m an occupational therapist working in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of a public hospital in Recife, Brazil. Every day, I have the privilege—and the responsibility—of accompanying premature babies and their families through some of the most fragile and formative moments of their lives.

Among all the babies I’ve cared for, there is one who left a lasting mark on me. She was born with a rare syndrome, incredibly delicate, and spent two months in the NICU. During that time, our bond was built not through dramatic interventions, but through the quiet power of presence. I would often go to her bedside just to change her diaper slowly, calmly—so that she could have a positive experience of touch and human connection, even in the middle of so many wires and monitors.

There were days when there was no specific therapeutic plan for her. And still, I showed up. Because sometimes the most powerful thing we can offer is our presence, our gentleness, our intention.

And then, one day, she passed away.

Even though she had received every professional care possible—medical support, therapies, loving attention—that loss hurt deeply. But it also revealed something profound to me: that our work in neonatal care is not only about helping babies recover or thrive. It’s also about loving them fully, even when there are no guarantees. It’s about being a bridge, even when the road is short.

Her story changed me. It reminded me that care isn’t measured only in days of life, but in the love and intention that fill those days. That sometimes, a baby’s mission is brief—but never meaningless. And that if there is love, there is purpose.

I’m sharing this not to romanticize pain, but to honor the truth that sometimes, it teaches us the most. If you are a parent, a caregiver, or a healthcare professional reading this—what you do matters. Even when it feels small. Even when it ends sooner than you hoped.

Your presence matters. And that, in itself, is a form of healing.–Marília Rêgo

THE BASICS

Key points

- Brief interactions in the NICU can have an impact on caregivers’ self-efficacy and bonding with their newborn.

- It’s important to train healthcare professionals to actively listen, use nonverbal gestures, and empathize.

- Comforting and compassionate patient-provider interactions may be the most healing interventions for family.

For parents and family caregivers, navigating a child’s medical condition can be the most stressful of life experiences. When a child begins their life in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), caregivers are often catapulted into feelings of uncertainty, fear, and powerlessness. No one anticipates that having a new baby will involve being in a hospital indefinitely relying on physicians and nurses for lifesaving care. Sensitive and compassionate parent-provider interactions are critical for parents to develop feelings of safety, trust, and hope during this overwhelming period.

Even brief interactions at the NICU bedside may make or break a caregiver’s sense of self-efficacy and confidence in caring for their babies (Labrie et al., 2021). A 2021 meta-analysis by Labrie and colleagues revealed that these frequent moments with providers have far-reaching impacts on parents’ coping ability, their understanding of their baby’s condition, their participation and satisfaction with care, and their ability to attach to and bond with their newborn. Most importantly, these effects were often related to routine bedside interactions – not solely to structured conversations at family conferences.

Personal experiences

The authors are both psychologists who have worked in medically complex settings with patients across the lifespan. The perspectives and tips are based on working with patients experiencing unexpected medical adversity as well as personal experience.

Joanna: Six years ago, my son spent the first month of his life in the NICU following an unexpected birth trauma, leading to a sudden loss of blood and oxygen. Waiting for medical updates felt unbearable. It was as though the MRI machine and medical team held the key to our family’s future. Emotions fluctuated like a rollercoaster from shock and numbness, to anxiety, anger, grief, and – eventually – hope.

Occasionally, in an effort to manage our expectations, health care team members reminded my husband and me of how “medically fragile” our son was at birth. These “warnings” tended to overshadow positive news and made me question my gut sense that our baby would get well. I preferred updates on even the smallest steps our son made: hearing that he moved his tongue slightly when given a drop of breastmilk felt uplifting.

Simple, previously taken-for-granted events were deeply felt on a visceral level. When the elevator was out of order and the physician walked me up the stairs from the NICU to my own hospital floor, his support and kindness deepened the level of trust in the entire treatment team. My obstetrician standing patiently and quietly beside me at our son’s NICU crib provided immense comfort. Oftentimes, silence, presence, and accompaniment are the most healing interventions.

No matter how much time has passed, these patient-provider verbal and nonverbal communications remain imprinted in the memories of NICU parents and caregivers.

Bedside manner

“Bedside manner” has long been held as an important virtue of effective medical care. Ancient Greek writing urged providers to be “sober, not a winebibber” and to act “not with head thrown back (arrogantly).”

Teachings have evolved over time and have been incorporated into medical school education. Despite this development, issues of time, financial pressures, and the complexity and urgency of medical needs due to advances in technology may interfere with effective patient-provider communication.

Current healthcare education highlights the importance of listening to the entire message or question from the patient or family caregiver without interruption, showing genuine interest through nonverbal gestures including tone of voice, using understandable, non-jargon language, providing comfort, and putting oneself in the patient’s shoes to cultivate empathy (Deepak, 2024).

Examples of unhelpful vs. helpful communication

Unhelpful

- Opening with, “I have some bad news,” which can lead to catastrophic thinking

- Using jargon such as “We need to do a needle stick,” which can evoke an upsetting image

- Describing the situation as “very severe,” even if true

Helpful

If appropriate, starting with, “Your baby is okay, but I wanted to share that…”

Using accurate language such as “We need to draw some blood.”

Using specifics like, “The blood transfusion is helping your baby with the blood loss,” provides a degree of hope, even in dire times

Tips for fostering effective communication in the NICU

These tips apply to communication with mothers, fathers, other caregivers, and integral supports. Including all caregivers in communications can help ensure the whole family feels seen and acknowledged as important to the baby’s care.

Medical professionals can optimize communication and bedside manner by:

- Validating that what caregivers are experiencing is scary and difficult.

- Using comforting nonverbal communication: sitting down, giving full attention and listening deeply to the family’s concerns and questions, and using a calming, reassuring touch when appropriate.

- Letting family members know that providers are available and how to reach them.

- Acknowledging that uncertainty exists while also expressing specific efforts to make things better.

Family and friends can further enhance a sense of support by:

- Listening without offering advice. It is natural to want to lighten the mood or “fix” a problem. However, active listening and acknowledging how things are may be what the caregiver needs.

- Checking in after the baby leaves the hospital. Support may be strong at the beginning but tends to taper. However, parents may struggle with the adjustment to life after the NICU.

Psychology providers working with caregivers in the NICU can help by:

- Collaborating to make a list of questions or script in advance of medical appointments to ensure that concerns are addressed.

In navigating these challenging encounters with the medical team, caregivers can utilize the following communication strategies:

- Taking initiative in asking specific questions to convey self-efficacy and active hope.

- Making time to interact with their partner or other supports outside the hospital setting. Separation from the NICU and having conversations about other topics is a healthy way to cope.

Lessons learned

Just as parents/caregivers need to be highly attuned to subtle cues to develop secure attachments to their babies, the suggested communication tips highlight the importance of nonverbal communication. Voice tone, posture, eye contact, deep listening, and presence foster feelings of security and agency in the receiver.

As a psychologist who ended up on the receiving end of care, my own patients’ stories now resonate more deeply. Beyond what I could possibly learn in graduate school, the personal experience has informed the clinical wisdom of sitting calmly, presently, holding space for patients to discover their unformulated feelings, and being human to whatever emerges. I choose my words carefully – for they may never be forgotten.

Abstract:

The environment in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is often unpredictable and loud, leading to overstimulation and stress. A variety of negative auditory input, including alarms, respiratory support machines, speech, and other environmental sounds, occurs daily. When sound policies are implemented, they may help mitigate infants’ negative auditory experiences. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the auditory development of the fetus and NICU infant and the role that music might play in ameliorating the adverse effects of life outside of the protective womb. Of particular importance is the family’s role in using music to provide developmental care that supports auditory development while still meeting the infant’s medical needs, such as physiological parameters, weight gain, and reduced hospitalization length. Utilizing the mother’s singing has positive ramifications as an ideal source of auditory input, given the continuity and predictability of music’s acoustic properties, along with careful consideration of the infant’s auditory development across gestational age and the medical and developmental needs at that moment. In addition, when mothers sing to their infants in the NICU, it can have a significant impact on maternal mental health. Music therapy researchers have examined the use of the maternal voice for preterm and term infants; music therapists taught mothers to sing and use their voices to support their infants, resulting in increased singing at home and improved mother-infant bonding. This paper will discuss recommendations for auditory stimulation, based on years of music therapy research in the neonatal intensive care unit, to promote healthy neurologic development.

Introduction to Music Therapy:

Before discussing fetal and infant auditory development and the role of music and sound for preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), we would like to provide an overview of music therapy. While it might be considered a new field, the profession has existed as an organized entity in the United States since the 1950s. Music therapy is a healthcare profession in which evidence-based music interventions are used to address non-musical goals within a therapeutic relationship. Entry into the profession requires a Bachelor’s degree or completion of an Equivalency Program in music therapy. Eligibility to sit for the board exam depends on completing academic coursework and 1200 clinical training hours. Credentialed professionals use the term music therapist-board certified, “MT-BC,” which is provided through the Certification Board for Music Therapists (www.cbmt. org); music therapists must recertify every 5 years, and some states have licensure. The current professional organization is the American Music Therapy Association (www.musictherapy. org), which oversees student training .

Music therapists are trained to use music to address sensory, physical, cognitive, communication, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. We address these needs through evidence based interventions, often involving live, client-preferred music across multiple settings. Music therapists commonly work within the following settings:

• Medical hospitals/outpatient clinics

• Neurorehabilitation facilities

• Hospice/palliative care

• Psychiatric hospitals/community mental health centers

*Early intervention and day care treatment centers

• Public school systems

• Correctional facilities

• Private practice

This paper is based on the approach of the Institute for Infant & Child Medical Music Therapy. created by Dr. Jayne Standley at Florida State University in 2003. Standley established this approach by drawing on medical and developmental models, endorsing and teaching music therapy based on empirical evidence. There are other models of music therapy in the NICU, such as psychodynamic approaches, but we prefer to use this model since it closely aligns with the medical profession and developmental care of the preterm infant.

Auditory Development of the Fetus/Infant and Impact on Neurological Development

The NICU environment can increase preterm infants’ risk of long-term hearing impairment; however, it is essential first to understand how auditory development occurs in the womb. This is a highly intricate process that begins early within fetal development. At 23–25 gestational weeks, all major structures of the ear, including the cochlea, are in place, allowing the fetus to hear and process sounds in utero, with a consistent response to sound by 29 weeks of gestation. Beginning at 25 weeks, thousands of fine hair cells known as sensory receptors in the cochlea begin to respond to specific frequencies of sound. These hair cells are arranged tonotopically throughout the cochlea. As the fetus develops, it becomes finely tuned to various sound frequencies transmitted through amniotic fluid and skull bone vibrations. Starting at 28 weeks and throughout the third trimester of pregnancy, the auditory system is maturing as myelination of the auditory nerve enables auditory responses and processing between the cochlea and the brainstem . As the walls of the uterus thin towards the end of pregnancy, sounds of higher frequency (>500 Hz) gradually pass through the womb (13), preparing the fetus for language development after birth. During fetal development, the womb acts as a low-pass filter, promoting the healthy development of the cochlea by limiting exposure to higher-frequency sounds . Fetuses can safely process low-frequency sounds (250–500 Hz) between 25–27 weeks and high-frequency sounds (1000–3000 Hz) by 29–31 weeks . However, most sounds in the NICU environment exceed 3000 Hz or exceed the recommended maximum sound level of 45 decibels (dB) set by the American Academy of Pediatrics, making it difficult for proper cochlear development to occur and creating an acoustic gap between the NICU and the womb. Exposure to high-frequency sounds in the NICU can not only cause stress but also lead to apnea, hypoxemia, and inadequate oxygen saturation levels that can affect growth, neurodevelopment, and hearing impairment . To better support auditory and overall sensory development, there is currently a need to identify developmental care interventions, based on gestational age and medical status, that are embedded in a family-centered care model and support optimal neural network development. The clinical use of music in the NICU can reflect the predictable, rhythmic, and organized environment of the womb, supporting positive auditory development while yielding consistent, positive outcomes such as stabilization of physiologic parameters, increased weight gain, and shortened length of stay as well as a decrease in maternal stress, making it an optimal developmental intervention throughout an infant’s stay until discharge.

Clinical Use of Music by Gestational Age:

25–28 Weeks: The cochlea and auditory cortex begin to process sound at 25 weeks and are critical to the development of the auditory system; however, they are easily affected by sounds and care practices in the NICU environment . Starting at 26 weeks, the process of tonotopic tuning begins, in which hair cells in the cochlea are finetuned to specific frequencies of sound, which are then processed into electrical signals sent to the brainstem and auditory cortex . As stated earlier, infants between 25–27 weeks can efficiently process sounds between 250–500 Hz ; however, frequencies above 1000 Hz can adversely affect autonomic functions. A stimulus considered critical, especially for infants in the NICU, is the maternal voice, which typically resonates between 200– 300 Hz, making it optimal for auditory processing and early language development.

According to the literature, the maternal voice is the strongest acoustical signal for the developing fetus and has yielded positive effects not only on auditory system development but also on autonomic functioning and behavioral responses. Similar results have been reported for preterm infants born between 25 and 32 weeks of gestation: the maternal voice significantly decreased heart rate, suggesting possible improvements in autonomic stability and neurobehavioral development In addition, mothers of preterm infants often use “baby talk” when speaking to their infants, which has a regulatory effect on their behavior and lays the foundation for early language development.

The presence of meaningful sounds, such as the mother’s voice, is pertinent to the appropriate development of the auditory system, and music has been considered an impactful stimulus for infant development in the NICU when provided in a meaningful way. Lullabies have long been considered the most effective type of music for mitigating overstimulation in preterm infants, due to their simple, repetitive, and predictable structure. When using music for infants 25–28 gestation weeks, it is recommended to use live lullaby singing that includes a single female voice without additional instruments, slow tempo, little to no dynamic changes with limited pitch range, and repetitive play of each lullaby with a high degree of continuity among the lullaby music that is used. The recommended duration of music at this age is no more than 30 minutes based on infant response. Since the mother’s voice is preferred, live lullaby singing by the mother or caregiver is best to promote family-centered care. Maternal singing during kangaroo care is highly recommended and has a significant impact on both the infant and the mother, reducing infant distress and maternal anxiety. If recorded music is to be used, it is recommended to present it binaurally, following the same parameters as previously mentioned, while closely observing the infant to adjust the music/turning it off based on infant responses. If possible, a recording of the maternal voice is recommended. Classical music, nature sounds, musical toys, and white noise machines are not recommended, as they could be overstimulating due to their unpredictable or unorganized structure and do not provide the meaningful auditory input needed to support auditory development at this gestational age.

29–32 Weeks:

During this time period, tonotopic tuning of hair cells in the cochlea continues, and it is recommended that sounds/music remain between 250–500 Hz until 33 weeks, when the auditory system can safely process sounds at higher frequencies of 1000–3000 Hz . Lullaby music remains preferred for auditory development, and the aforementioned protocol should be used when providing either live lullaby singing or recorded lullaby music. The maternal voice is highly recommended at this time as it supports the auditory skills needed to process basic human speech sounds.

Preterm infants are considered to be at a high risk for developing language delays and impairments due to the lack of exposure to the maternal voice while in the NICU. Lullabies share characteristics with “baby talk” provided by the mother, such as simple prosodic contours, higher pitches, and short lyrical phrases that convey emotions necessary for promoting early language development and communication in preterm infants. Infants at this age can also discriminate between different phonemes, indicating the beginnings of language and speech development. Regarding music processing, it has been found that preterm infants at this age can detect differences in simple and complex beats/meters in auditory recordings, indicating early neural auditory discrimination .

33–36 Weeks: From 33 to 37 weeks, the fetus changes to process complex sounds, with differences apparent in the older fetus: a gradual increase in heart rate that did not change with sound levels. The authors stated that the older fetus might attend to the music. In contrast, the younger fetus might respond to the acoustic properties of the sound, such as pitch, loudness/intensity, and timbre. At this time, infants process higher frequencies of 1000– 3000 Hz.

Based on this information, it is crucial to continue to provide positive auditory input to infants in the NICU, including singing, reading, and speaking. If the infant is medically stable and responds positively to simple songs over several days, it is appropriate to progress to more complex songs. Thus, shifting from songs that have a simple melody, such as “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” which consists of 4 notes within a narrow range of a perfect fifth and contains two chords if an accompaniment is provided, to more complex songs, such as “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” consists of 6 notes within a range of a major sixth interval and has three chords if an accompaniment is provided. After an infant shows positive responses to music, such as cooing, smiling, turning towards the sound source, and maintaining heart rate and oxygen saturation within baseline levels before music listening, it may be appropriate to gradually introduce more complex and new songs into the routine.

Eventually, more complex songs might be beneficial, including songs with three chords and eventually four chords, longer song duration, and a chorus and verse. The overall goal is to provide auditory input to the infant systematically to prepare them for the home environment, including the car ride home from the NICU, during which the radio might be playing. It is important to start with simple, repetitive songs first to determine how the infant is handling sensory input, since what is appropriate one day might not be another due to new experiences (a first bath) or medical procedures (an eye exam). Also, infants who were born extremely low birthweight (ELBW) and/or have experienced significant amounts of respiratory assistance across time as well as those with major complex medical needs might not be ready for complex presentation of music at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA), while an infant born at 32 weeks might be ready for more complex songs at 35 weeks PMA. The presentation of music must be carefully considered by the families and medical team. The IRainbow

provides guidelines for the use of music and auditory input based on the infant’s medical stability and physiological maturity.

By 35 weeks, the fetus’s learning includes memory formation Thus, caretakers will want to continue to utilize songs and rhythmic books that have already been presented to the infant at an earlier age, but it is important to integrate new information through new songs. Infants habituate to repeated presentations of the same information, and auditory stimuli become less relevant; hence, musical mobiles and sound devices that loop the same song are still not advised for the NICU or even the home environment. Parents need to be involved in their infant’s care, including providing auditory input. Having lists of songs appropriate to musical complexity and medical and developmental needs (abilities) might be one way to involve parents in providing their infant with appropriate auditory experiences. Providing song lyrics will also help parents to remember and recall songs.

Parents need to be involved in their infant’s care, including providing auditory input . Having lists of songs appropriate to musical complexity and medical and developmental needs (abilities) might be one way to involve parents in providing their infant with appropriate auditory experiences. Providing song lyrics will also help parents to remember and recall songs.

When parents cannot visit the NICU, it would be beneficial to record the mother’s voice reading and singing to her infant to be played at the bedside. If recorded music is used, only music that has a single accompanying instrument, such as a guitar or piano, should be used. Researchers have found positive effects of singing combined with guitar accompaniment on both male and female infants’ physiological outcomes and length of hospitalization . Regarding the duration of musical and auditory stimulation, a longer duration would yield greater benefits, but there is potential harm when providing auditory input without research supporting the protocol. Eight hours of music per day, 4 hours during the day shift and 4 hours during the night shift, resulted in infants being hospitalized longer than the control group; hence, recorded music or other auditory stimulation should not be played continuously. Protected sleep, especially REM sleep, is pertinent and necessary for learning . Meaningful auditory input is necessary for infant development; thus, providing live singing or recorded music might be best during clustered care when infants are awake or in quiet sleep. For example, when infants are awakened for diaper changes and vitals prior to feeding, the time frame before feeding might help the infant achieve an alert, awake state. Similarly, singing soothing lullabies after feeding might help infants fall asleep. Of particular importance is providing auditory stimulation in a quiet environment, as preterm and term infants cannot discern meaningful auditory input if the noise exceeds 60 decibels.

36 Weeks and Older:

Auditory processing skills continue to develop and refine from 36 weeks PMA through term. By term, the fetus adjusts to specific elements of music, such as sound intensity (loudness) and frequency (high versus low notes), among others. In an fMRI study, infants were aware of previously heard musical elements, such as tempo, which led to positive connections in the auditory cortex . Consequently, families should continue using past songs and books, and introduce new stimuli if the infant shows positive responses to auditory stimulation to decrease habituation. Mothers should use their voice and be encouraged to sing. Medical staff should continue to control the amount and quality of auditory stimulation in the NICU environment to reduce adverse developmental outcomes.

As infants evince positive responses to music and are medically stable and thriving, they might be ready for movement to music that involves midline orientation and hand-to-hand play (such as a modified “Patty Cake” or “Itsy Bitsy Spider”) (53). Since newborns discriminate between speech and other sounds, indicating a sensitivity to the frequencies and timbres of speech (49, 53), infants should be encouraged to engage in cooing and babbling. Songs such as “Little Green Frog” and “If All the Raindrops” involve distinct lip and tongue movements that might help prompt infants to respond with vocalizations or facial movements.

Summary:

Using music to support auditory development can be highly effective, particularly given the infant’s gestational age and medical stability. The above recommendations are based on evidence-based research and should be followed to reduce the risk of harm. Music can also be used in the NICU to encourage parent involvement in their infant’s care and development. Many neurosensory programs, such as SENSE and iRainbow©, advise parents to sing and/or talk to their infants to enhance auditory development. The above recommendations provide clear guidance on how best to use music within these programs and may increase parent involvement, as music is an easy way to bond with and care for an infant in the NICU. Clinical and developmental care staff should adhere to the above guidelines to best support auditory development while promoting family-centered care for preterm infants and their families.

Source:https://www.neonatologytoday.net/newsletters/nt-dec25.pdf

PREEMIE FAMILY PARTNERS

Spilling the Tea is an educational series for new preemie moms and dads brought to you by TEACUP Preemie Program®. These brief but in-depth videos will explore aspects of prematurity including emotional and mental effects, the NICU environment, breastfeeding & pumping, reclaiming attachment & bonding, and others. Preemie parents share their experiences through intimate video journals, and experts in infant development and prematurity offer guidance and information. In this second episode of Spilling the Tea, two preemie moms share about the effects of the premature birth on their own mental health. Licensed Mental Health Counselor Jenny Estrada offers insights and information about PPD, Anxiety, and PTSD to help preemie moms know when and how to find help.

INNOVATIONS

This review explores methodological considerations in estimating racial disparities in mortality among very preterm infants (VPIs). Significant methodological variations are evident across studies, potentially affecting the estimated mortality rates of VPIs across

racial groups and influencing the perceived direction and magnitude of racial disparities. Key methodological approaches include the birth-based approach versus the fetuses-at-risk approach, with each offering distinct insights depending on the specific research questions posed. Cohort selection and the decision for crude versus adjusted comparison are also critical elements that

shape the outcomes and interpretations of these studies. This review underscores the importance of careful methodological planning and highlights that no single approach is definitively superior; rather, each has its strengths and limitations depending on the research objectives. The findings suggest that adjusting the methodological approach to align with specific research questions

and contexts is essential for accurately assessing and addressing racial disparities in neonatal mortality

IMPACT:

● Elucidates the impact of methodological choices on perceived racial disparities in neonatal mortality.

● Offers a comprehensive comparison of birth-based vs. fetuses-at-risk approaches in the context of racial disparity research.

● Provides guidance on the cohort selection and adjustment criteria critical for interpreting studies on racial disparities in very preterm infant mortality.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-024-03485-w

ABSTRACT

Aim

Extremely preterm infants (born before 28 weeks of gestation) face substantial risks of mortality and severe morbidity. This study aimed to identify early clinical predictors of survival and major complications in this vulnerable population in order to guide individualized neonatal care strategies.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted on 102 infants born between 22+0 and 27+6 weeks of gestation and admitted to a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit from 2017 to 2020. Demographic, perinatal, and clinical variables were extracted from their medical records. Survival and morbidity outcomes were compared across gestational subgroups. Statistical analyses included chi-square, t-tests, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results

The overall survival rate was significantly influenced by gestational age, birth weight, and the type of respiratory support received. Infants born at 22-25 weeks exhibited lower survival rates and higher incidences of respiratory distress syndrome, invasive ventilation, and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Mortality was independently associated with lower birth weight (p<0.0001), invasive ventilation (p=0.0014), and the presence of hemodynamically significant PDA (p=0.0243). In contrast, longer durations of non-invasive ventilation correlated with improved survival (p<0.0001). ROC analysis demonstrated high predictive performance for birth weight [area under the curve (AUC)=0.82] and non-invasive ventilation duration (AUC=0.96).

Conclusion

Early postnatal respiratory parameters, birth weight, and cardiovascular status are critical determinants of survival in extremely preterm infants. Optimizing non-invasive ventilation strategies and timely PDA management may enhance outcomes. Notably, the rate of antenatal corticosteroid administration was markedly low in our cohort, which may have contributed to adverse respiratory and survival outcomes, underscoring the need for improved perinatal care strategies in extremely preterm births.

Babies born prematurely can have a number of complications at birth, simply because they are brought into the world before their organs are fully developed. One complication is called patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

PDA occurs when a small fetal blood vessel in the heart remains open after birth. Much like trying to drink through a straw with a hole in it, the condition can cause unnecessary stress on the heart and lungs, as they have to work harder to push blood throughout the body.

However, treatment for the condition remains controversial among neonatologists, cardiologists, and pediatricians alike. Results from a clinical trial published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA, brings physicians one step closer to an answer.

Led by neonatologist Matthew Laughon, MD, MPH, the study found that using medication to treat patent ductus arteriosus was associated with higher mortality compared with an expectant, or “watchful waiting,” approach.

“There is wide variation in treatment of PDA in preterm infants,” said Laughon, who is a professor of perinatal-neonatal medicine at the UNC School of Medicine and lead author on the paper. “Some clinicians always treat, and some clinicians never treat. We need to know which one is better for babies”

A total of 482 extremely pre-term infants (born between 22 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation) with PDAs were enrolled in the clinical trial. All of the infants were born within affiliated hospitals of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network, a collaborative network of neonatal intensive care units across the United States.

Participants were randomized into two treatment groups: those to receive pharmacologic treatments (either acetaminophen, indomethacin, or ibuprofen) and those to receive expectant management, or a “wait and see” approach.

Researchers wanted to know which intervention would decrease the risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a serious lung condition caused by life-saving efforts to ventilate and oxygenate into the lungs, by the time the infants reach 36 weeks adjusted age.

Through statistical analysis, researchers found that infants given expectant management had treatment had nearly double the chance of survival before 36 weeks.

“This trial showed no benefit of active treatment of the PDA in extremely preterm infants,” wrote Laughon. “In fact, it identified a higher chance of survival for expectant management, consistent with

emerging data on the effects of early (i.e., prior to one or two weeks after birth) pharmacologic PDA treatment.”

The medications themselves, which are all commonly used to treat the PDA, can also alter the immune system, reduce blood flow to the intestine, or cause gastrointestinal mucosal injury. These effects may lead to serious conditions like sepsis or the death of intestinal tissue, called necrotizing enterocolitis.

Results from this trial will help inform new treatment strategies for preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus, saving more lives and putting families on a path towards growth and healing.

This work was supported by The National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

The three Betos of Zumba—creator Alberto Perez and partners Alberto Aghion and Alberto Perlman—are not often fully recognized for the powerful global impact their vision has inspired. Zumba has become one of the most effective, joyful, and widely embraced exercise programs in the world, blending cardiovascular training, strength-building, and flexibility through energetic, Latin- and globally inspired music and dance. Workouts feel less like exercise and more like a celebration, leaving participants feeling uplifted, embraced, confident, and connected. Today, more than 15 million people take part in Zumba classes each week across roughly 200,000 locations in about 180 countries, a testament to its extraordinary reach and influence on global physical activity, community health, and engagement. This sense of unity comes alive each year at the international Zumba Convention, where instructors from around the world gather and the shared humanity of the global community is visible—our oneness acknowledged, individuality celebrated, and human creativity welcomed with open arms. Every Zumba class has the power to create a space of acceptance, belonging, and shared joy. A great Zumba class reminds us to celebrate the uniqueness and precious presence of ourselves and others. Zumba is, at its core, a love dance—and there is no power greater than love.