Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia,is a country in Mainland Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline along the Gulf of Thailand in the southwest. It spans an area of 181,035 square kilometres (69,898 square miles), dominated by a low-lying plain and the confluence of the Mekong river and Tonlé Sap, Southeast Asia‘s largest lake. It is dominated by a tropical climate. Cambodia has a population of about 17 million people, the majority of which are ethnically Khmer. Its capital and most populous city is Phnom Penh, followed by Siem Reap and Battambang.

The quality of health in Cambodia is rising along with its growing economy. The public health care system has a high priority from the Cambodian government and with international help and assistance, Cambodia has seen some major and continuous improvements in the health profile of its population since the 1980s, with a steadily rising life expectancy.

A health reform of Cambodia in the 1990s, successfully improved the health of the population in Cambodia, placing Cambodia on a track to achieve the Millennium Development Goal targets set forth by the United Nations. One such example is the Cambodian Health Equity Fund, largely financed by the country itself, created in 2000 to increase access to free health care to around 3 million poor people. The Fund, which pays for traveling expense and even daily allowance for anyone accompanying a patient, has resulted in increasing health care seeking among Cambodians who otherwise could not afford any kind of medical care. As a result of the reform, mortality rates significantly dropped. Similarly, life expectancy at birth in 2010 was 62.5 years, a 1.6 folds increase from 1980.

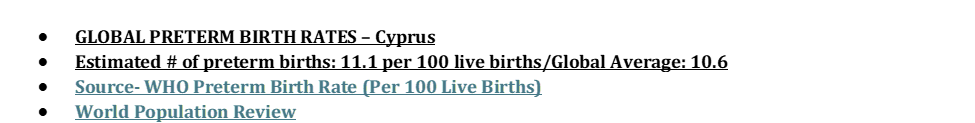

- GLOBAL PRETERM BIRTH RATES – Cambodia

- Estimated # of preterm births: 10.5 per 100 live births

- (Global Average: 10.6)

- Source- WHO Preterm Birth Rate (Per 100 Live Births)

COMMUNITY

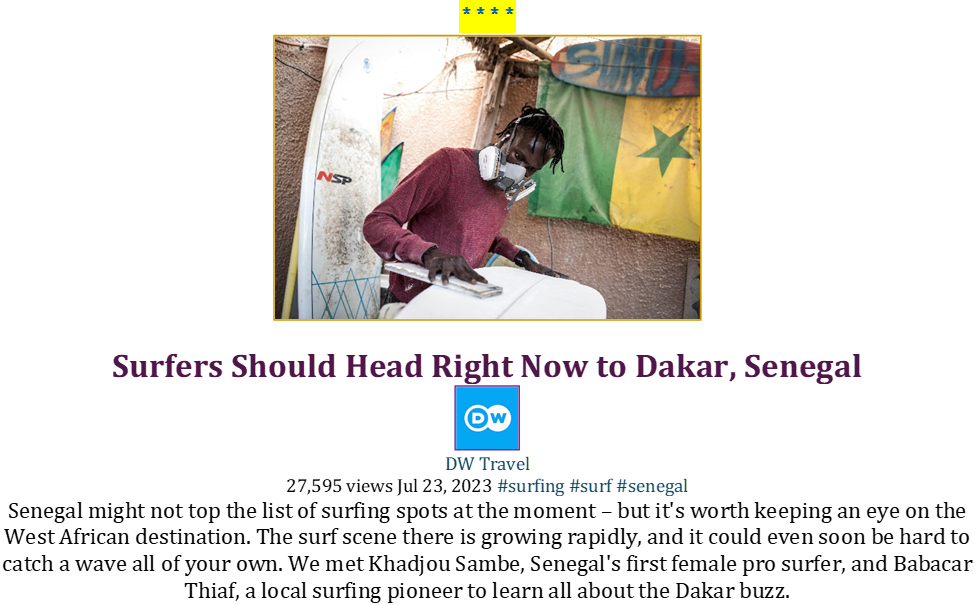

Cambodia’s sustained progress in improving maternal, newborn and child health

20 February 2025

At the beginning of the 2000’s, Cambodia faced alarming maternal, newborn and child health indicators. The maternal mortality ratio stood at 437 per 100 000 live births, while newborn and child mortality rate accounted for 37 and 124 per 1000 live births respectively. Limited infrastructure, a shortage of skilled birth attendants and financial constraints hindered progress. To tackle these challenges, the Cambodian government, with support from WHO and key partners, embarked on a transformative journey to strengthen maternal and newborn health services and ensure equitable access to quality care.

Today, skilled birth attendance is near universal, with 98.7% of births attended by trained health professionals and 97.5% of women giving birth in a health facility. Between 2014 and 2021-2022, neonatal and under-five mortality rates declined by 54%, from 18 to 8 and from 35 to 16 per 1000 live births respectively, far exceeding the global average reduction of 14% during 2015-2022. Cambodia achieved its Sustainable Development Goal targets for reducing neonatal and under-five mortality eight years ahead of schedule.

Strengthening health systems

Cambodia’s investments in health systems and workforce capacity have been instrumental in driving progress. Midwifery training programmes have equipped health workers with essential skills to provide safe, high-quality care, including routine antenatal care, essential intrapartum care, postnatal care, and management of childbirth complications. Deployment strategies have ensured that even remote health centres are staffed with skilled birth attendants.

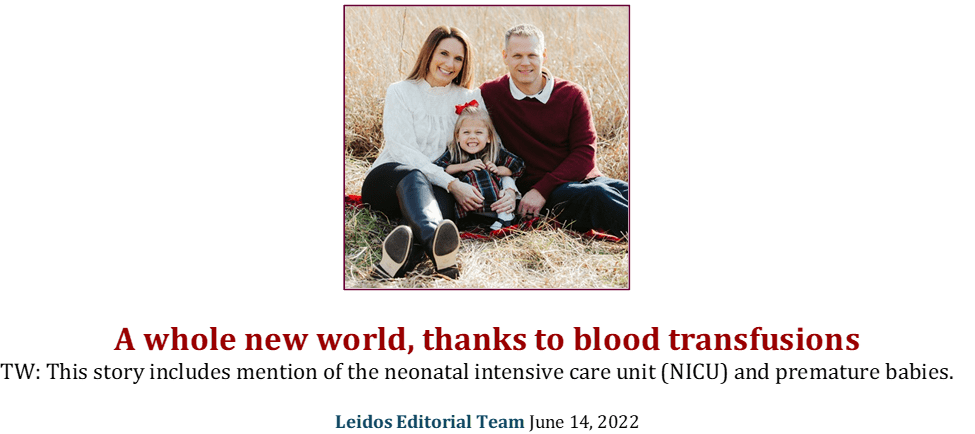

To incentivize facility-based deliveries, the government introduced a delivery incentive programme for health teams in 2007 and launched cash transfer programmes for pregnant women and infants from poor families in 2019, targeting the critical first 1000 days of life. These initiatives encourage families to seek comprehensive antenatal and postnatal care, ensuring access to a full package of essential health services. Financial mechanisms such as health equity funds, cash transfers and fee exemptions have alleviated economic barriers, making institutional care more accessible to vulnerable populations.

Improvements in water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructure have also contributed significantly to better health outcomes. An integrated routine primary health care delivery system has been established across provinces and districts, ensuring that essential services effectively reach communities. Health promotion and behaviour change campaigns have played a vital role in encouraging exclusive breastfeeding and antenatal care-seeking behaviours.

Strong leadership and strategic framework

A key milestone in Cambodia’s progress has been the strong leadership of the Ministry of Health, which has provided clear strategies for advancing maternal and newborn health. Two main coordination platforms — the Sub-Technical Working Group for Maternal and Child Health and the Early Essential Newborn Care (EENC) Coordination Committee — were established and have convened regularly to align efforts within the Ministry and with health partners.

With technical support from WHO and funding from the Korea Foundation for International Healthcare (KOFIH), the EENC Coordination Committee plays a crucial role in harmonizing national and sub-national efforts, monitoring progress through regular reviews, mobilizing resources to scale up EENC practices, and ensuring consistency in care delivery while addressing service gaps.

Recognizing the need for a strategic and systematic approach to newborn care, the committee led the development and adoption of the Five-Year Action Plan for Newborn Care (2016–2020). The plan emphasizes scaling up EENC and institutionalizing evidence-based practices, integrating key life-saving and cost-effective interventions — such as routine immediate care for all newborns under “The First Embrace” approach, as well as measures to prevent and care for small or sick newborns.

By 2023, EENC coaching was implemented in 89.4% of health facilities (1187 out of 1328), surpassing the 80% target. Kangaroo Mother Care for preterm and low birthweight infants has been scaled up to two national hospitals and ten provincial and district referral hospitals, while a national protocol for EENC in Caesarean sections, introduced in 2019, has standardized care nationwide.

“Maternal, newborn and child health are essential components of investing in human capital. Providing quality care for mothers and newborns brings immense benefits — not just for families, but for entire communities and economies. Cambodia’s coordinated approach to maternal and child health serves as an inspiring model for the region and globally. It demonstrates what can be achieved with strong national leadership, dedicated health workers and sustained partnerships,”stated Dr Marianna Trias, WHO Representative to Cambodia.

Remaining challenges

Despite significant achievements and high coverage of antenatal care and facility-based deliveries by trained health personnel, challenges persist. While maternal mortality has declined, it remains high at 154 deaths per 100 000 live births, primarily due to haemorrhage and pregnancy-induced hypertension — both preventable causes. Greater efforts are needed to get on track to achieve the 2030 target of 70 deaths per 100 000 live births. Similarly, child malnutrition continues to impact long-term productivity, with 22% of children under five stunted and 10% wasted for over a decade.

Disparities between urban and rural areas and gaps in facility capacity to provide quality essential services require targeted attention. Addressing unmet family planning needs and expanding adolescent-friendly services are crucial, particularly as rural adolescent girls aged 15–19 experience significantly higher birth rates than their urban peers.

The way forward

Moving forward, further reducing maternal and neonatal mortality requires a stronger focus on enhancing the quality of care. Building on significant improvements in coverage, efforts should prioritize improving the quality of basic routine care during antenatal and intrapartum periods, including emergency obstetric care, alongside establishing robust referral systems for cases requiring higher-level care. Achieving this will require both the strengthening of quality improvement mechanisms with enhanced monitoring and the implementation of targeted improvement actions.

The Fast-Track Initiative Roadmap for the Reduction of Maternal and Newborn Mortality (2025–2030) aims to accelerate progress by scaling up interventions, sustaining quality care and addressing service delivery gaps. To support its implementation, WHO will assist in developing a comprehensive country action plan and support the Coordination Committee for Strengthening Quality of Care and Wellbeing of Women, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health to ensure effective coordination and execution.

Bringing clean water to where life begins: a neonatologist’s story from Ukraine

12 June 2025

These are the words of Galina Dmytrova, a neonatologist at Chuhuiv Central Hospital in the Kharkiv region of Ukraine. To her patients, the support Galina and her colleagues provide make a difference between life and death.

“They are already under enormous stress because of the war and now we are facing water shortages again. Before the war, you’d turn on the tap and not think twice. But now, under daily shelling, the electricity goes out, and with it, the water too,” says Galina.

5 water stations set up across Kharkiv city and the wider region in Ukraine continue to allow hospitals to provide essential care despite the war. Among them is Chuhuiv Central Hospital. The stations were installed in 2025 by WHO with funding from the European Union and in partnership with Ukraine’s Ministry of Health.

For communities regularly affected by attacks that disrupt electricity and water supply, this support ensures access to clean, safe water for both patients and health workers, which is critical in maternity wards, where hygiene and continuity of care are vital.

“In our hospital, thanks to WHO and the European Commission, we now have a water treatment system. I’m deeply grateful. It’s hard to explain the importance – especially for mothers and their babies. Many people actually can’t believe women are still giving birth under such harsh conditions. But they are, and I truly admire them,” Galina adds.

Those are our babies

In 2024, some 179 children were born in the Chuhuiv Central Hospital in the Kharkiv region. This year, the birth rate is similar; in the first 3 months of 2025, hospital staff oversaw more than 45 births.

“That’s our maternity ward, our babies, around 15 every month – even while the war goes on,” Galina tells us.

The certainty and assurance that care is available, that there is a hospital nearby, gives people hope. A functioning hospital is a reminder that life goes on. The opposite is also true; when health facilities are damaged or attacked in conflict, it not only deprives communities of access to health care. It also deprives them of hope.

“When the war started, I was new to Chuhuiv. I didn’t know the area that well. One night, a woman in labour came very late and explained they’d been looking for a boat. The bridge to her village had been destroyed – so, to get here, they had to cross the river. But they did it, because they knew here was a hospital that could help,” says Galina.

Fortifying our commitment to pediatric academic medicine during turbulent times

Academic Medicine, with its tripartite mission to advance medical science, cultivate the next generation of healthcare professionals, and provide exceptional clinical care, offers unparalleled opportunities to shape the future of evidence-based healthcare delivery and inform health policy. Biomedical innovation developed through collaboration between academic medicine and public health can improve health at the individual and population health levels including mapping disease trends and improving treatment outcomes. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) economic impact report published in 2022, every one dollar spent by the AAMC member medical schools and teaching hospitals contributes $1.62 to the United States economy. Unfortunately, medical schools and teaching hospitals continue to face reductions in government funding for research and education support and have faced decades of under-reimbursement for publicly insured care, often delivered in these systems which also serve as safety net health care systems across the country.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) revealed that the nation’s supply of physicians engaging in research continues to decline, with increased competition for decreasing available federal funding. Pediatric research is disproportionately impacted by gaps in funding, directly impacting the scientific innovation aimed at improving child health outcomes. As advanced technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) balanced with rapidly evolving scientific discoveries offer novel and dynamic clinical approaches to care, these persistent funding gaps often lead to pediatric care falling behind adult care delivery. With an estimated 646,000 researchers supported by federal grants, 48% of whom are students and trainees, the cross-cutting dependence and impact of federal funding on research and education is undeniable. Therefore, to mitigate further impact in pediatric academic medicine, continued promotion of NIH-funded pediatric research must leverage the understanding that return on the investment continues over the lifespan of the growing child to adult.

In the article by Arnaez and colleagues, Dr. Garcia-Alix is celebrated for his longitudinal contributions and global reach in academic medicine, specifically in field of Neonatal Neurology. By understanding that at least 30% of neonates admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs) present with neurological pathology or other conditions impacting brain development, he recognized the importance of studying neuroprotective factors that impact these children’s morbidity. For Dr. Garcia-Alix, this area of interest sparked a career long passion. His dedication was evident, while advancing and supporting academic education and mentorship of his learners, generously investing time and role modeling for further generations. With the appreciation of the life-course model for his neuro-neonatal patients, Dr. Garcia-Alix, translated the overarching goal of improvement of functional outcomes by creating Brain-Aware Care, a family-centered, multidisciplinary approach targeting protecting an infant’s developing brain at the earliest stages. He recognized and appreciated that neuro-neonatal care delivery differs requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, family-centered approach tracking continuity of care as a baby grows, as is the continued research to understand how to develop appropriate care guidelines and protocols for developing, growing and thriving children. Dr. Garcia-Alix dedication and contributions as a physician scientist and educator with global impact on generations of patients in the field Neonatal Neurology is a testament of the longitudinal investment and support required to achieve the return on investment in child health outcomes in pediatric academic medicine.

Fiscal pressure on the future of pediatric academic medicine

The goal of pediatric academic medicine is to continue to develop and support clinician scientists like Dr. Garcia-Alix throughout their careers, who are committed to innovation, clinical care, and education. However, the fiscal pressure on pediatric academic medicine for the past several years, balancing under-reimbursed Medicaid clinical activity, rising labor costs, inadequate availability of pediatric extramural funding, and insufficient graduate medical education funding, is leaving teaching hospitals and partnered medical schools to find novel ways to advance this pediatric academic mission. Institutional-level investment in clinician scientists (e.g., 3 year contracts where early career faculty have time to successfully compete for a career development grant) are less feasible as financial pressure mount from funds flow models in Children’s Hospitals. Similarly, competition for institutional (e.g., KL2) and external (e.g., K23) grants are increasing as paylines are decreasing. With recent changes in administration policy, opportunities for first-generation scientists and those underrepresented in biomedical research (e.g., diversity supplements, MOSAIC award) are now unavailable. Protecting NIH funding, particularly money appropriated to child health research, is essential to promote the mission of pediatric academic medicine. Moreover, given diminishing availability of federal extramural funding, reviewing alternative, non-traditional academic sources of funding mechanisms for research including private industry, venture capital or foundation funding will be necessary to explore to uphold the tripartite mission of our pediatric academic mission.

In addition to research challenges, pediatric residency training programs are in jeopardy. Since the annual budget for graduate medical education is supported through the Congressional appropriations processes, strategic consideration of alternative platforms of support for retention, learner mentorship, and workforce pipelines are critical to ensure continued access to care for our pediatric population. Mentors can be instrumental at different stages of learners, from guiding students in explicit academic knowledge, to implicit knowledge of professionalism, ethics and the art of medicine.9 Retention of faculty is critical during times of economic stressors in academic medicine and leaning on mentorship and sponsorship as a key strategy, especially given pay inequity between pediatric and adult academic clinicians. Finally, evaluation of the economics of health professions education (HPE), is critical with ongoing cost-constrained academic medicine environments, especially with graduate medical education funding at risk.

Call to action for the health of our nation’s children

We need to reinforce and double-down on our commitment to the pediatric academic medicine mission-centered goal in improving the health and well-being our children and youth through investments in advancing science, cultivating our next generation of pediatric learners and improving clinical care for our pediatric patients. With several decades of Medicaid under-reimbursement, challenging degradation of federal pediatric extramural funding compared with adult funding, and even greater disparities in pediatric workforce shortages, families are facing a stark reality in worsening access to pediatric healthcare which will only grow in the upcoming years due to Medicaid cuts. We must continue to educate legislators and government officials that children require the same level of extramural funding (if not greater), in efforts to evolve even greater investment on return investment over the life-course trajectory. We must advocate for reimbursement parity greater than Medicare, especially understanding the discrepancy between Medicaid enrollment and Medicaid expenditure on children, being roughly 50% and 20%, respectively. Finally, we must educate that pediatric academic medicine, with its medical schools and teaching hospitals, contribute to the economy and health of the United States.

Call to action

- Support the Bipartisan Legislation H.R. 3890 (Sewell, Fitpatrick)- Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2025- Educate your local legislators on the importance of Pediatric Education workforce pipeline and its’ impact on access to care, especially in rural communities

- Continuing to unequivocally advocate for Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education (CHGME), and budget appropriation within the annual Labor Health and Human Services Appropriations Process for the House and Senate Committees

- Support NIH funding increases for Pediatric Research funding, which will increase and parity (and increase) for pediatric extramural funding for research to improve the evidence-based decision-making, and uphold trust with patients, families and society

- Continue to educate our legislators about the life-course model in child health, and the return on investment, with the reality that for every $1 investing in early intervention, there is a return on investment from $1.26 to $17.07 for every child invested in the United States.

- Finally, ensure that with the rapid advancing in technology, including artificial intelligence (AI), gaps do not arise regarding access to therapeutic tools between pediatric and adult populations in healthcare.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-025-04621-w

Abstract

Background: Perinatal loss is a profoundly complex form of grief, often linked to heightened risk of prolonged bereavement and adverse mental health outcomes. Perinatal grief rooms-private, supportive spaces within healthcare settings-aim to help families process their loss, spend time with their baby, and create meaningful memories in a respectful environment. While bereavement care has received growing attention, the role of the physical environment in supporting grief remains underexplored.

Objective: To synthesize current evidence on how dedicated physical spaces can support individuals and families after perinatal loss, and to identify priorities for research, design standards, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Literature searches were performed across PubMed, PsycINFO, Medline (OVID), Embase, ScienceDirect, SCOPUS, SciELO, and Google Scholar using terms, such as “perinatal grief rooms”, “bereavement rooms”, “angel suites”, “butterfly suites”, “snowdrop suites”, “cloud rooms”, “designated units for perinatal loss”, and “birthing + bereavement suites”. The review examined (1) the current role of physical spaces in the perinatal loss experience, and (2) how their availability and design may influence grief outcomes.

Results: Of the 17 articles meeting inclusion criteria, only 4 (24%) referenced bereavement rooms, and just 3 (18%) noted the need for formal protocols-without offering concrete examples. No studies evaluated implementation, design standards, or measurable impact on grief, mental health, or family well-being. This lack of empirical evidence and standardized guidance underscores a critical gap that limits integration of therapeutic environments into perinatal bereavement care.

Conclusion: Despite increasing recognition of the importance of bereavement care, dedicated grief rooms remain under-researched and inconsistently implemented. Advancing this field will require rigorously designed studies, development of design standards, and collaborative partnerships among healthcare providers, researchers, policymakers, and design experts to ensure equitable access to therapeutic spaces for grieving families.

Source: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40986076/

HEALTHCARE PARTNERS

Why it matters:

Harnessing the power of a multidisciplinary team carries vast potential for effectiveness and problem-solving—while achieving high-performance with diversely skilled stakeholders requires adroit management.

The Center for Innovative Leadership (CIL) exists to support and accelerate the production of new research on leadership in today’s dynamic, complex organizations and bring research to life through engaging student experiences and powerful industry partnerships.

Summary: In healthcare it is common practice for multidisciplinary teams to be involved in efforts to improve the quality and safety of patient care. The perioperative period, which encompasses the time before, during, and after a surgical operation, is a prime target for multidisciplinary improvement efforts because of the diversity of professional roles and care delivery settings involved. Failure to achieve improvement targets in this context is often attributed to lack of resources or resistance to change.

A recent study counters this view, suggesting failure is more likely to be due to the way the multidisciplinary improvement team is led and how well it collaborates. Successful improvement projects depend on effective leadership—from designing the team, communicating a shared vision, planning the project, through to creating a collaborative approach to getting work done, and a structured training and feedback process.

A new study distils existing literature and gathers expert opinions on leadership and high-performing teams to offer practical guidance on those factors and behaviors relevant to the delivery of perioperative improvement projects, but also to leading multidisciplinary teams outside of healthcare.

High-performing healthcare services continually seek to improve patient experience and outcomes. One key area of focus for improved performance has been the perioperative period—the time leading up to, during, and after surgery. Unfortunately, perioperative improvement teams often fail to achieve their goals and when this happens the blame is often ascribed to resistance to change or lack of resources.

A recent study highlights that another important – yet overlooked – reason why t improvement projects fail is because of the way multidisciplinary improvement teams are designed, how they are led, and how the multidisciplinary teamwork is managed.

The study, from Christina Yuan and Michael Rosen, Faculty Affiliates at the Center for Innovative Leadership at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, in collaboration with Tasnuva Liu, Benjamin Eidman, Della M. Lin, and Elizabeth Wick, contends that taking time to pre-plan and continually reflect on how team leadership behaviors are enacted is the best way to ensure team success—yet this is often overlooked.

The researchers surveyed a range of thought leaders and team leaders with deep-rooted experience in perioperative work to discover the leadership behaviors and practices considered to be most relevant to planning and implementing perioperative improvement initiatives.

Based on their findings the researchers recommend the following six key areas leaders should consider when designing and leading teams to deliver perioperative improvement projects—recommendations that carry implications for the management of multidisciplinary and cross-functional teams in a wider context too:

Design and Define

It is important to clearly define the aims of the mission, and to choose a team that includes all stakeholders and the right mix of skills and roles—allowing flexibility and ensuring that roles are not too rigidly defined. It is also wise to include those who are skeptical about improvements, as well as those who are more receptive, so as to understand the scope of the challenge ahead and ideally to bring skeptics on board.

Manage

Leaders should create an environment where collaboration is prioritized and fine-tuned. Through discussion, establish effective processes for getting work done and delegating tasks. With agreement leaders should identify challenging but realistic goals for the team. They should monitor and report on progress and help the team recover from any small set-backs.

Sustain

An environment of psychological safety should be created, where team members feel they have a voice and their opinions are acknowledged. Leaders should communicate regularly to everyone to show how the project is progressing and to build a collective understanding of what is being achieved and what more might be done. This should be framed as a positive way to learn from successes and failures as opposed to seeking compliance.

Train and Feedback

Listening, asking good questions, and soliciting feedback are essential leadership behaviors. In a multidisciplinary team it is important everyone participates and is heard, including less vocal team members. This interaction can be the basis for providing skills training and promoting continuous learning—appreciating that failures can be opportunities for learning.

Manage Team Boundaries

It is a leader’s role to clarify the boundaries between the core project team and other groups and departments, as well as to be a liaison with these entities. It is vital to obtain senior leadership buy-in at the outset of the project and to maintain this throughout with regular reporting on progress, successes, and any potential barriers. Messages should be brief and individualized to address each senior leader’s particular concerns.

Manage Organizational Context

Aligning the team’s efforts with organizational needs is key. Here an important factor is for senior leaders to ensure access to data the team needs to make decisions and do their work. Removing barriers to data sources and providing the team with opportunities to ask senior leaders questions and get information as needed is also the leader’s responsibility.

In a busy healthcare setting, where the delivery of a perioperative improvement project will be one of many priorities for the members of the assigned multidisciplinary team, above all team leadership must be clear and precise. It must ensure all members of the team understand their roles, feel free to participate fully, and are empowered to achieve to the best of their abilities. There are innumerable management theories and practices that might be suggested to accomplish this.

The value of Yuan and Rosen’s study is that it helps to distil the essence of what is really required for effective team leadership in this context.

Source: https://carey.jhu.edu/articles/leadership-lessons-multidisciplinary-teams-healthcare

PREEMIE FAMILY PARTNERS

New insights into brain and behavior development:

Recent research provides new insights into significant brain and behavioral changes in the baby’s first six months after birth, laying a foundation for later physical, cognitive, and social development. Preparation in utero leads to infant behavioral responses that ensure survival, and the caregiving environment provides safety and protection during these early months. Brain development accelerates, and regulation of biophysiology is demonstrated in respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems, as well as in behavior.

Newborns and young infants often exhibit behaviors that signal caregivers to provide protective and nurturing responses. Caregivers, usually the baby’s parents, typically respond to the baby’s signaling. Mutual reinforcement of behavior leads to the dyad becoming adapted and regulated in early infancy. Mismatches in the baby’s explicit behavioral signaling and/or challenges in the caregiver’s reading and/or responding to the baby’s behavior in these early formative months can affect later social, emotional, and cognitive development.

Signaling behavior:

Signaling behaviors such as crying, vocalizations, alertness, and face scanning prompt interaction with others. Crying signals distress and is likely to promote immediate caregiver response. Facial expressions, such as smiling, brow knitting, and pouting, often elicit an emotional response from the baby’s caregiver. The resulting dyadic exchanges promote ongoing social interaction. As brain development proceeds at a rapid pace, the transition from reflexive to volitional behaviors typically occurs around 2-4 months. These more intentional behaviors lead to more sophisticated behavioral repertoires and social bids.

The responsive caregiving environment and mutual interaction between caregivers and their baby during this time contribute to the development of increasingly regulated behavior. Caregivers of newborn and very young infants need support to understand babies’ available signaling behaviors, as these behaviors have a significant impact not only on early caregiving relationships but also on brain development.

Signaling behavior of hospitalized babies:

Early-born or sick newborns are at a disadvantage in the development of signaling behavior. Their experience as a fetus and during delivery can interfere with the development of or overwhelm effective behavioral communication. Early-born babies have not had experiences during the last weeks of their fetal life that contribute to more organized behavioral responses. Their reflexes may be weak or hard to elicit, arousal and visual regard may be limited, and physiologic instability may affect responsiveness. Necessary medical support may also overwhelm their meager energy and/or fail to recognize their efforts to signal.

In addition to early birth and/or medical concerns, the caregiving environment in intensive care is vastly different from the “expected” one for a more typically developing baby and can thus affect foundational brain and behavioral development. It is well known that long-term effects on brain development, social/emotional, and cognitive development in babies hospitalized at birth are recognized as less than optimal. Early birth, medical issues, and hospitalization can interfere not only with a baby’s ability to provide clear signals but also with caregivers’ ability to interpret them.

Intensive care professionals are typically trained in medical assessment and intervention, which until recently have not included behavioral assessment. Berry Brazelton was a pediatrician who took the lead in understanding the behavioral repertoire of newborn babies. Heidelise Als, one of his protégés, extended that understanding to babies born early. She developed the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) and emphasized observing and interpreting babies’ behavior. Based on those assessments, caregiving recommendations are developed to help the baby achieve regulated behavior and thus achieve their own developmental goals. Since her early work, most NICUs now incorporate identification of at least some behavioral signals and implement strategies to support babies’ development.

IFCDC standards provide a foundation for supporting signaling behavior:

At the center of the IFCDC standards concept model is an emphasis on the baby as an interactor in their relationship with their primary caregiver, typically the mother. Woven into each of the other principles is the understanding that the baby influences how they are cared for both by family members and by intensive care professionals. The model implies that the baby’s individualized interaction with the environment of care influences their physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development.

Each of the six evidence-based areas of developmental care emphasizes the importance of understanding the baby’s behavioral communication to fashion an individualized approach to their caregiving experience. Additionally, each of the six areas includes an emphasis on supporting the baby’s primary caregivers, typically the parents, to observe, interpret, and respond to the baby’s behavioral signals. Early-born and medically fragile babies’ signals can be challenging to interpret. Professional staff must have a thorough understanding of the baby’s signaling behavior to provide individualized caregiving and support parents in knowing how best to care for their baby.

The continuum after discharge:

The continuum after discharge: Leaving intensive care marks a transition into early infancy and involves a multitude of brain and behavioral changes. During these foundational months, rapid brain development is reflected in significant behavioral changes. As noted above, reflexes become modified into volitional events, and signaling behaviors become dependent on the baby’s environment of care. As the medically fragile or early-born baby becomes more physiologically and behaviorally regulated, their signaling becomes more socially responsive.

The primary caregiver, on the other hand, may still be affected by the intensive care experience and be hesitant to interact with their previously fragile baby vigorously. It is postulated that as the baby becomes clearer in their communication, more intentional, and ready to interact, the parent can be less responsive to their bids.

Although targeted interventions for caregivers in their early relationships with their baby begin in the NICU, they must be continued after discharge, as behavioral changes in the first months are rapid, and it is often difficult to understand how best to respond.

Caregivers’ understanding of their baby’s signaling behavior as it changes over time must be supported and reinforced by knowledgeable professionals for at least the first six months of the baby’s corrected age, and sometimes longer, depending on the baby’s adaptation during this period. As brain and behavior, as well as parenting skills, are still developing, individualized dyadic care should be provided early and frequently after discharge and should continue for at least six months.

Conclusion:

The continuum of brain and behavior development from the fetal to the newborn to the early infancy period evolves in the context of the baby’s environment of care. The behavior the baby uses to signal their need for caregiving changes dramatically over the first six months, and caregiving responses that regulate the baby’s behavior lay the foundation for later physical, cognitive, and social emotional development. Babies born preterm or medically fragile are typically less effective in their signaling behavior. Due to the altered environment in which they develop and the myriad factors that influence their parents’ responsiveness to their behavior, they and their parents need supportive measures to assess, interpret, and provide support for early development. The current IFCDC standards incorporate supportive strategies into both the concept model and the evidence-based practice areas. Because brain and behavior are particularly vulnerable during the first six months, there is a need not only to understand and respond to their behavior in intensive care but also to continue this understanding and response after discharge for at least the first six months.

Source: https://neonatologytoday.net/newsletters/nt-jan26.pdf

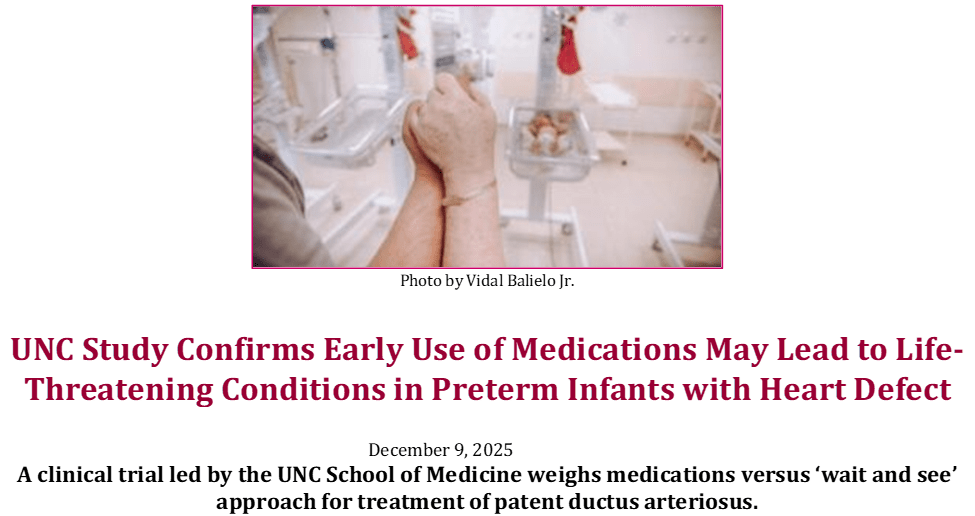

Breastfeeding a premature baby requires special care, patience, and close monitoring—especially during the transition from tube or bottle feeding to the breast. In this hospital-based guide, a healthcare professional demonstrates how to safely breastfeed a growing preterm infant while ensuring adequate milk intake.

This video explains how pre- and post-feeding weight checks are used to accurately measure how much milk a premature baby consumes. You’ll learn correct breastfeeding positions, how to maintain proper body alignment, and how to achieve a deep, effective latch. The guide also helps parents distinguish between nutritive sucking and comfort sucking, recognize early signs of fatigue or stress, and follow essential safety protocols such as monitoring breathing patterns and proper burping techniques.

Ideal for parents of premature babies and NICU families, this video supports confident, safe breastfeeding during a critical stage of infant development.

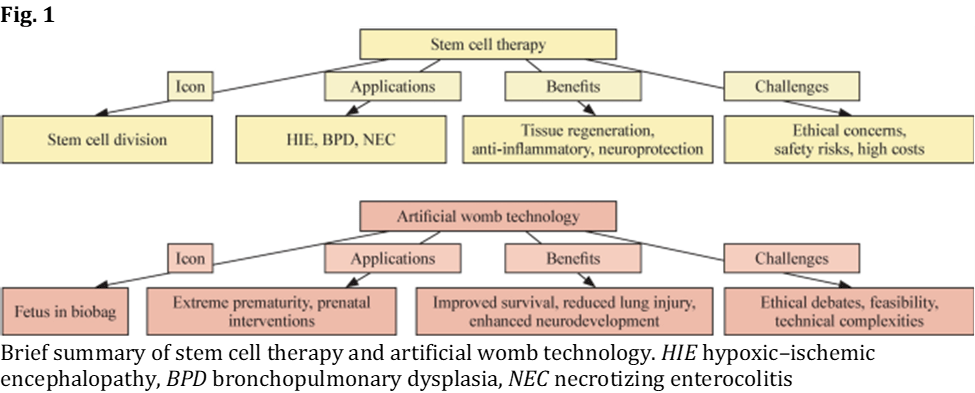

INNOVATIONS

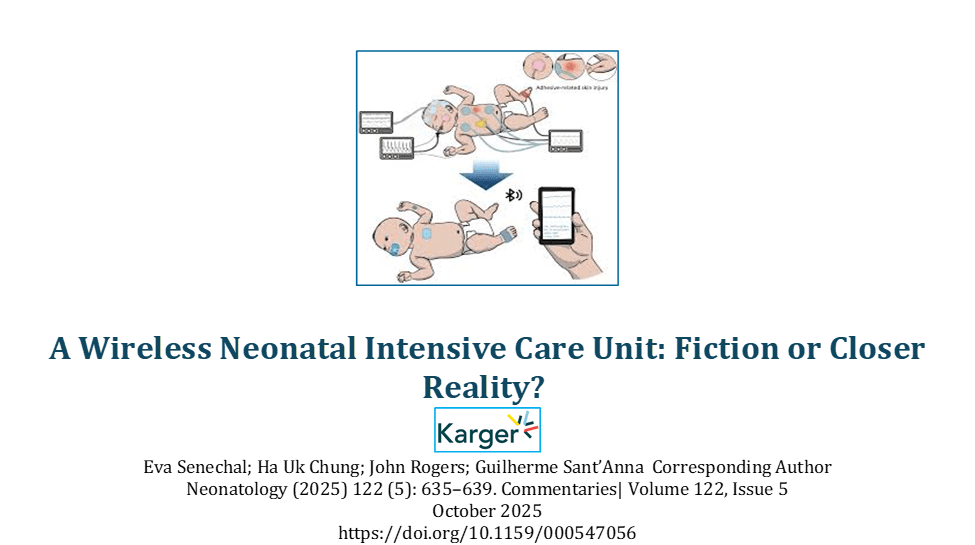

“In the 1960s, when the first NICUs opened, premature infants had a 95% chance of dying. Today, they have a 95% chance of survival” – Dr. Rahul K. Parikh, a pediatrician from California, published in August 2012 in the New York Times . This incredible shift in survival can be considered a great example of the conquest of modern neonatal medicine. Among many technological advancements, the ability to continuously monitor vital signs such as heart rate and respiratory rate, was followed by closed loop body temperature (T) control, blood pressure assessment, and finally by continuous and non-invasive monitoring of oxygen saturation. Monitoring of these vital signs was paramount for the assessment of well-being and detection of pathophysiological states in tiny patients, allowing for adjustments or initiation of treatments or interventions that are lifesaving.

There is no question that neonatal technology has advanced tremendously over the last 60 years and parents have become very approving of this. In the book From Surviving to Thriving, Fabiana Bacchini, the mother of a twin baby boy born at 27 weeks, wrote: “I was able to watch in happiness and gratitude, all the technology that exists to keep these tiny beings alive.” Later, it also became clear that, despite the important role of technology, it can also cause fear and anxiety for parents. Fabiana mentioned that the first time she entered the NICU “I did not see a baby, I saw wires, monitors and a breathing machine” .

Indeed, current technology for vital signs monitoring uses several skin sensors connected to the bedside monitors by wires and cables. In most patients, raw signals, average values and trends of heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation are continuously displayed. However, this system carries some challenges for patients, parents, and healthcare professionals (HCP) as the multiple wires can tangle around the infant body, restrict the patient’s movement, and cause discomfort or pressure sore. Hence, regular care involves frequent removal, reapplication, and readjustments of the sensors, which may harm the fragile neonatal skin, cause pain, and/or interrupt resting or sleeping. For parents, not much information is available on what are their perspectives on these vital signs monitoring systems. Some small surveys have reported that the presence of multiple wires and cables can cause intimidation and additional stress, acting as a barrier to skin-to-skin contact for fear of disconnecting the sensors or wires, or interfering with regular monitoring . This technology may also increase HCP’s workload as wires and cables may touch contaminated surfaces or become soiled with urine, blood or stools, increasing the risks of nosocomial infections. Consequently, nurses must constantly inspect, sanitize, reposition, or replace components of the system.

Is a Wireless NICU Possible?

Neonatal intensive care units manage a diversity of health problems with variable degrees of severity and patient maturation. To develop a wireless system that can be used during the first days of life in a 400 g extremely preterm infant born at 22–23 weeks of gestation and a 4-kilo term infant born with perinatal asphyxia is a real challenge. Furthermore, there are some more stable infants that are just feeding and growing, or infants with chronic problems that require prolonged hospitalizations. Noticeably, the needs of these populations are different, creating challenges for the development of new vital signs monitoring systems. As an example, an extremely preterm infant in the first days of life spends most of the time quiet, sleeping inside the incubator, and has very sensitive skin that can easily be damaged by skin adhesives and sensors. In these cases, non-contact technologies may play a very important role, at least for the monitoring of heart rate and respiratory rate. This is not the case with more stable and mature infants that are active, and where parents can constantly hold and promote kangaroo care (KC). Therefore, the adoption of new monitoring technologies needs to consider those different needs, be very familiar with the technology advantages and limitations, and develop protocols and proper training for all healthcare providers involved.

Is a Wireless NICU Desirable?

Although wired vital sign monitors are the standard, they are frequently cited as obstacles to key aspects of family-integrated care and routine clinical practice. Wireless vital sign monitoring technologies are increasingly being explored as a potential solution to these issues. However, there is limited research available which quantitatively or qualitatively examines how key NICU stakeholders such as parents and HCPs, perceive the current monitoring system and these wireless innovations.

The small number of existing studies have highlighted that the wires and sensors used in current systems interfere with skin-to-skin contact and KC, limit parents’ ability to hold or touch their infants, and contribute to a highly technical environment that many find overwhelming. Survey and interview studies consistently show that parents perceive the wires as intimidating and as contributing to their anxiety . HCPs also express widespread concerns with the current systems, especially regarding the physical clutter created by wires, challenges with positioning and handling of infants, risk of pressure sores from adhesives, and the frequency of false alarms .

These concerns have led to growing interest in wireless monitoring as a possible solution. While research on parent and HCP in this area is very limited, all existing studies show optimism toward the adoption of wireless technology. Parents have generally responded positively, citing benefits such as reduced anxiety, possible easier interaction with their infant, improved KC, and enhanced infant comfort. However, there are some apprehensions related to signal reliability, sensor size and appearance, battery duration, and potential risks such as radiation exposure . Similarly, HCPs have voiced strong support for wireless monitoring, highlighting its potential to reduce handling difficulties, decrease false alarms, and improve comfort for both infants and families . Importantly, they also emphasize areas of concern, including reliability, safety related to radiation, and costs . In particular, the absence of economic feasibility studies is a significant gap in the current literature.

Overall, the available evidence indicates that wireless monitoring is a promising advancement, with support from key stakeholder groups in the NICU. The shift away from wired systems could improve key aspects of neonatal care, particularly KC and parental engagement, while also addressing some of the frustrations voiced by HCPs. However, to address these challenges, and ensure new technologies will be adopted by NICU staff and parents, concerns around reliability, safety, and cost must be addressed through careful user-centered design, and rigorous research including clinical evaluation. Future research should prioritize that wireless systems not only meet regulatory and clinical standards but are also feasible and acceptable for daily use in the NICU.

What Wireless Technology for Neonatal Vital Signs Monitoring Is Available or Emerging?

Non-Contact

A large number of small studies have investigated the use of non-contact vital sign monitoring in the NICU. Most studies used a single-device system and monitored respiratory or heart rate using offline analysis. The following technologies have been tested: red, green, blue cameras, infrared cameras, monochrome cameras, depth cameras, and radar, primarily for respiratory rate and heart rate monitoring . Non-contact sensors are typically placed at the head or foot of the infant’s incubator or crib. In some cases, the sensor cannot collect data through the plexiglass and may require either an open incubator or a small opening to maintain a clear line of sight. Depending on the technology and algorithms used, a defined Region of Interest within the sensor’s visual field may be designated for vital sign extraction.

These studies generally featured small sample sizes and short recording durations of <1 h . Nearly all exclusively focused on accuracy by comparing novel non-contact methods to a reference measurement using the Bland-Altman method. Analyses of heart rate and respiratory rate using this method revealed low bias and moderately acceptable 95% limits of agreement. Feasibility outcomes were rarely explored and measured using metrics such as the amount of usable data or processing times. No studies explored outcomes related to safety, although this can be expected as these monitoring methods pose no threat to the fragile neonatal skin.

While these technologies show promising preliminary results, several concerns remain. First, feasibility concerns remain as most devices rely on an uninterrupted clear view of the infant. How it would perform in situations where the infant is moving, clothed, or receiving care needs to be better clarified. Additionally, a systematic review of non-contact technologies applied the QUADAS-2 assessment and revealed several areas of concerns regarding risk of bias and applicability due to lack of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria and small sample sizes . Furthermore, many studies lacked key basic descriptors of the population, such as age and weight, making it difficult to ensure a representative range of NICU patients such as those requiring respiratory support or in incubators were included in the research. Additionally, some studies provided incomplete descriptions of reference measurements, only naming them as “standard” or “routine” monitoring, limiting the ability to determine the risk of bias. Unfortunately, most non-contact studies lack a conflict-of interest statement.

Ultimately, non-contact technologies may represent an appealing monitoring solution for some of the most vulnerable infants in the NICU, such as extremely premature infants with extremely fragile skin. This research area is rapidly growing as non-contact studies often utilize commercially available cameras and present low research risks for patients. However, concerns regarding the ability to perform reliably for prolonged periods in a real NICU environment and across a range of patients require further exploration and validation.

Wireless Wearables

Studies focusing on wearable devices provide slightly more detailed information regarding participant selection criteria and larger sample sizes. Emerging classes of wireless sensors in the form of soft, flexible, skin-like (“epidermal”) platforms have the potential to redefine practices for monitoring in the NICU, with additional possibilities for use in the home. Recent work at Northwestern University shows that a pair of devices of this type, each of which gently and non-invasively adheres to the fragile skin of a premature neonate, is capable of capturing complete, clinical grade vital signs information without any wires or cables . These devices include distributed flexible electronic components with stretchable interconnects; all embedded in strategic layouts within medical-grade silicone encapsulating structures. The designs optimize for conformal interfaces to the skin at relevant anatomical locations. In pilot studies on patients in NICU settings, these technologies achieved high accuracy and fidelity similar to those of traditional wired monitors. Extensions enabled by additional sensors allow for precise measurements of body sounds, relevant to cardiac and respiratory monitoring, with additional capabilities in tracking gastrointestinal activity . Specifically, high-bandwidth microphones and accelerometers yield seismocardiograms, lung sounds, bowel motility, and even the spectral and temporal features of crying and other forms of vocalization. In this way, these advanced technologies can not only capture vital signs and physiological signals but also an array of important biophysical metrics of health status, beyond those addressed with conventional NICU hardware.

Commercial translation is also gaining momentum. As an example, Sibel Health (Sibel Health, USA) has secured successive FDA 510(k) clearances since 2021 for its ANNE® One sensor platform, a pair of chest and foot patches to continuously monitor heart rate, respiratory rate, skin and core temperatures, oxygen saturation and biomarkers. It is also noteworthy that ANNE One® is currently under investigation in NICU at Montreal Children’s Hospital with the aim of create a wireless NICU. Meanwhile, other emerging technologies, focusing on more specific modalities, include Bambi Belt (Bambi Medical, the Netherlands) and Boppli® (PyrAmes, USA) for monitoring ECG/EMG and blood pressure, respectively.

Collectively, efforts with wireless technologies signal a paradigm shift to transform neonatal care with fewer risks and burdens, and to improve clinical workflow and patient safety. With continued refinement and real-world validation, wireless multimodal sensors are poised to enhance monitoring precision, promote a patient-centric environment, and ultimately give our most vulnerable patients a gentler start to life . With that, a wireless NICU became a much closer to reality than just fiction.

Abstract

Vaginal cervical cerclage and progesterone are established treatments for prevention of pregnancy loss and prematurity. There is limited data to assess the effect of these treatments in combination. The objective of this study was to investigate the association between progesterone and no progesterone treatment on pregnancy outcomes in women at high risk of preterm birth who had received a vaginal cervical cerclage.

This is a secondary post-hoc analysis of women recruited to the C-STICH randomised controlled trial, which recruited in 75 obstetric units in the UK between 2015 and 2021. In the C-STICH trial, women with a singleton pregnancy, receiving a vaginal cervical cerclage due to a history of pregnancy loss or premature birth, or if indicated by ultrasound, were randomised to cerclage with braided or monofilament suture, with a primary outcome of pregnancy loss, defined as miscarriage, stillbirth, or neonatal death in the first week of life. In this secondary analysis, the primary outcome was pregnancy loss, defined as miscarriage and perinatal mortality, including any stillbirth or neonatal death in the first week of life. Secondary maternal outcomes included miscarriage and previable neonatal death; stillbirth; gestational age at delivery; preterm pre labour rupture of membranes, and sepsis. Secondary neonatal outcomes included early/late neonatal death and sepsis. For each outcome, regression models were fitted adjusting for prespecified prognostic variables.

From the 2,048 women recruited to C-STICH, 1943 (95%) women had a vaginal cerclage placed and available progesterone data. Of these, 834 (43%) women received progesterone and 1,109 (57%) did not receive progesterone. In women with primary outcome data available, in our predefined analysis pregnancy loss occurred in 49 (5.9%) of 832 women who received progesterone and 91 (8.3%) of 1,103 women who did not receive progesterone (adjusted* risk ratio 0.70 (95% confidence interval (CI) [0.50, 0.99]); adjusted risk difference −0.02 (95% CI [−0.04, −0.001], *adjusted for indication, obstetric history, surgical technique, and maternal age). Further exploratory analysis excluding women who had termination of pregnancy for foetal anomaly demonstrated a nonsignificant reduction in the risk of pregnancy loss. Key limitations of this study include a non-randomized trial design and unknown confounding relating to variation in progesterone use.

In women with a vaginal cervical cerclage and concomitant progesterone there appears to be an association with a reduced risk of pregnancy loss. This combination therapy may be an important opportunity to further reduce the risk of pregnancy loss in this high-risk cohort.

Source:https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004513

First Responders

Stronger Together: Building Friendship, Community, and Courage as Neonatal Womb Warriors

Building friendships is one of the most powerful ways we grow as Neonatal Womb Warriors. As preemie survivors, we begin life in a world of uncertainty, strength, and resilience that most people never experience. That journey can sometimes feel isolating—but it doesn’t have to be. When we build friendships with peers, colleagues, and our broader community, we create spaces where our stories are understood, our challenges are validated, and our victories are celebrated. These connections remind us that we are not alone—we are part of a network of survivors, supporters, and advocates who stand together.

Friendship also teaches us how to trust again—trust in others, and trust in ourselves. Many preemie survivors grow up navigating medical complexities, transitions, and moments of vulnerability. Through friendships, we learn how to communicate our needs, listen to others, and build mutual support systems. Whether it’s a colleague who understands the importance of flexibility, a friend who encourages us during a difficult moment, or a mentor who helps us see our potential, these relationships become pillars of strength. They help transform survival into thriving.

Stepping outside of our comfort zone is often where the most meaningful connections begin. It can feel intimidating to introduce yourself, to join a new group, or to share your story—but courage lives in those small steps. For Neonatal Womb Warriors, getting out of our comfort zone is not just about social growth; it’s about reclaiming our voice and our place in the world. Each time we reach out, collaborate, or say yes to a new opportunity, we expand what is possible for ourselves and for others who may be watching and learning from our example.

At its heart, friendship is teamwork. It is showing up for one another, lifting each other up, and building something stronger together than we could alone. As a community of preemie survivors, families, clinicians, and advocates, we are all part of a shared mission: to help every warrior survive, grow, and thrive. When we lean into friendship and community, we build not only support systems, but movements of compassion, advocacy, and hope. And that is the true strength of a Neonatal Womb Warrior.