JORDAN

PRETERM BIRTH RATES – JORDAN

Rank: 16 –Rate: 14.4% Estimated # of preterm births per 100 live births

(USA – 12 %, Global Average: 11.1%)

Jordan: officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is an Arab country in the Levant region of Western Asia, on the East Bank of the Jordan River. Jordan is bordered by Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Israel and Palestine (West Bank). The Dead Sea is located along its western borders and the country has a 26-kilometre (16 mi) coastline on the Red Sea in its extreme south-west. Jordan is strategically located at the crossroads of Asia, Africa and Europe. The capital, Amman, is Jordan’s most populous city as well as the country’s economic, political and cultural centre.

Jordan is classified as a country of “high human development” with an “upper middle income” economy. The Jordanian economy, one of the smallest economies in the region, is attractive to foreign investors based upon a skilled workforce. The country is a major tourist destination, also attracting medical tourism due to its well developed health sector. Nonetheless, a lack of natural resources, large flow of refugees and regional turmoil have hampered economic growth.

Health:

Life expectancy in Jordan was around 74.8 years in 2017. The leading cause of death is cardiovascular diseases, followed by cancer. Childhood immunization rates have increased steadily over the past 15 years; by 2002 immunisations and vaccines reached more than 95% of children under five. In 1950, water and sanitation was available to only 10% of the population; in 2015 it reached 98% of Jordanians.

Jordan prides itself on its health services, some of the best in the region. Qualified medics, a favourable investment climate and Jordan’s stability has contributed to the success of this sector. The country’s health care system is divided between public and private institutions. On 1 June 2007, Jordan Hospital (as the biggest private hospital) was the first general specialty hospital to gain the international accreditation JCAHO. The King Hussein Cancer Center is a leading cancer treatment centre. 66% of Jordanians have medical insurance.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jordan

Please join us in a Musical Moment….

Adham Nabulsi – Han AlAn (Official Music Video)

| أدهم نابلسي – حان الآن

Nov 20, 2020 Adham Nabulsi

COMMUNITY

Kat is a surviving twin, born at 24 weeks gestation. Her brother, my son, Cruz died at or shortly after birth. I was very surprised to learn that the tiny baby making a very big sound was a girl. Research related to neonatal outcomes for preemie twins is interesting. Further research into this fascinating subject will provide a foundation for both prevention and treatments supporting preemie survival and wellness.

Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm twins by sex pairing: an international cohort study

Original research (11/12/20) January 2021 – Volume 106 – 1

Abstract

Objective Infant boys have worse outcomes than girls. In twins, the ‘male disadvantage’ has been reported to extend to female co-twins via a ‘masculinising’ effect. We studied the association between sex pairing and neonatal outcomes in extremely preterm twins.

Design Retrospective cohort study

Setting Eleven countries participating in the International Network for Evaluating Outcomes of Neonates.

Patients Liveborn twins admitted at 23–29 weeks’ gestation in 2007–2015.

Main outcome measures We examined in-hospital mortality, grades 3/4 intraventricular haemorrhage or cystic periventricular leukomalacia (IVH/PVL), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment and a composite outcome (mortality or any of the outcomes above).

Results Among 20 924 twins, 38% were from male-male pairs, 32% were from female-female pairs and 30% were sex discordant. We had no information on chorionicity. Girls with a male co-twin had lower odds of mortality, IVH/PVL and the composite outcome than girl-girl pairs (reference group): adjusted OR (aOR) (95% CI) 0.79 (0.68 to 0.92), 0.83 (0.72 to 0.96) and 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98), respectively. Boys with a female co-twin also had lower odds of mortality: aOR 0.86 (0.74 to 0.99). Boys from male-male pairs had highest odds of BPD and composite outcome: aOR 1.38 (1.24 to 1.52) and 1.27 (1.16 to 1.39), respectively.

Conclusions Sex-related disparities in outcomes exist in extremely preterm twins, with girls having lower risks than boys and opposite-sex pairs having lower risks than same-sex pairs. Our results may help clinicians in assessing risk in this large segment of extremely preterm infants.

Source: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-318832

Where Life Begins: Reducing Risky Births in a Refugee Camp

March 6, 2019 By Elizabeth Wang

Zaatari camp, the largest Syrian refugee camp in the world, sits less than 12 kilometers away from the border between Syria and northern Jordan. Rows of houses disappear into the desert, making it hard to tell where the camp begins and ends. Metal containers pieced together like patchwork are home to around 80,000 refugees. The remnants of tattered UNHCR tents cover holes in the walls. Almost seven years after the camp opened, this dusty sea of tin roofs has evolved into a permanent settlement.

When I entered Zaatari camp to begin my internship with the Women and Girls Comprehensive Center, I saw signs of resilience and humanity everywhere—colorful murals of smiling children, barefoot boys playing soccer, a wedding dress shop. Perhaps the greatest proof that life goes on can be found in the camp’s maternity wards, which see an average of 80 births per week, along with 14,000 consultations per week for expecting mothers. About 1 in 4 of the Syrian refugees living in Zaatari are women of reproductive age. According to UNFPA, 2,300 women and girls in Zaatari are pregnant at any one time. The extremely high fertility rate demonstrates how vital it is to facilitate access to quality reproductive and maternal health services during complex emergencies.

At the Women and Girls Comprehensive Center in Zaatari camp, which is run by the Jordan Health Aid Society and supported by UNFPA, refugee women of all ages receive services such as family planning, pre- and post-natal care, vaccinations, gynecological check-ups, and culturally sensitive information sessions. Every day, the clinic delivers five to seven babies. As of September 27, 2018, the clinic has had 10,089 safe deliveries and zero maternal mortalities, a stunning achievement that remains posted on a scoreboard outside the clinic’s gates.

Risky Pregnancies, Dangerous Deliveries

Despite this success, giving birth in Zaatari is not without dangers. The high prevalence of non-communicable diseases (such as anemia, diabetes, and hypertension) among Syrian refugees—and especially the inadequate management of these chronic conditions when they are fleeing conflict—increase health risks during and after pregnancy. Domestic and gender-based violence, which spike during complex emergencies, also cause extreme harm to women and girls.

One of the greatest challenges facing the Women and Girls Comprehensive Center involves caring for pregnant adolescent girls and young women under 20 years old. Due to instability, displacement, and poverty, the rate of child marriage among Syrian refugees is more than four times what it was in pre-crisis Syria. For Syrian refugees in Jordan specifically, the rate has doubled in the last four years. Consequently, many of these girls have multiple children before they even reach adulthood.

Seeing girls 16 years old and younger, in pain and alone in the delivery room, was one of the most difficult experiences of my time in Zaatari. As adolescents, they are much more likely to experience risky pregnancies, as well as premature birth and children with low birth weight, than women over the age of 20. Most of these girls are not aware of the risks of early marriage and pregnancy, and often do not feel safe during delivery.

At the center, refugees can access various forms of family planning, including birth control pills or IUDs. The midwives and doctors also host informational sessions on reproductive health topics, such as healthy prenatal behaviors and the risks of child marriage. The center’s oldest midwife, who everyone fondly refers to as “Mama,” makes home visits around the camp to discuss family planning and women’s health with families.

Despite the clinic’s efforts to encourage postponing and spacing pregnancies, the family planning services offered are not always used. Some women and girls are pressured by their husbands and families to avoid contraceptives and continue producing children without adequate time for recovery in between births. One patient I met at the clinic was famous in Zaatari, the midwife told me in a hushed voice, for having 12 children, all by cesarean section, over the course of 12 years. Women and girls who had IUDs placed often came back soon after to get them removed, per their husbands’ demands. Many Syrians feel obligated to have a lot of children to compensate for the family and friends killed in the war or to increase the likelihood that their children will survive.

Cultural Sensitivity Saves Lives

To save lives, we need to not only offer reproductive health services, but ensure they are culturally sensitive as well. Unlike other host countries, Jordan does not face large language or cultural barriers when providing care to Syrian refugees. Jordanians and Syrians speak similar Arabic and come from predominantly Muslim societies with shared values. This is an advantage for healthcare providers in Zaatari because they already have a good understanding of their patient population, which facilitates patient-provider trust and overall better quality care.

For example, when treating a woman who insisted on fasting for the religious holiday of Ramadan while pregnant, the Jordanian midwives were the best people for the job. As Muslim women themselves, they had a deep understanding of the woman’s motivations and could explain the serious health consequences of her decisions while still respecting the significance of the religious practice. By practicing empathy and non-judgment, they were able to help this woman find a balance between health and faith without alienating the patient and discouraging her from seeking care in the future.

New Beginnings

Early in my internship, we transported a woman in premature labor to a bigger hospital in Mafraq, the next closest city. As we all tried to maintain our balance in the back of the bumpy ambulance, the baby’s head began crowning. We pulled over to the side of the road and safely delivered her baby right there.

This is where life begins in Zaatari: in the back of dusty ambulances with missing windows, in delivery rooms with flies buzzing, in clinics where Jordanians and Syrians work together to protect women and children. Despite the enormous challenges facing these refugees and the healthcare workers seeking to help them, every day is the first day for another new life.

Elizabeth Wang is an intern with the Maternal Health Initiative. In 2018, she spent six months in Jordan studying humanitarian action, during which she interned at the Jordan Health Aid Society in both Amman and Zaatari camp.

Sources: Al Jazeera, Conflict and Health, European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, National Public Radio, PRI, Save the Children, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, World Health Organization.

Countries prepared for the climate emergency have had fewer COVID deaths

Countries where individuals look after each other and the environment are better able to cope with climate and public health emergencies, research by King’s Business School has found.

The paper published in World Development explores the role of climate risk, preparedness and culture in explaining the cross-country variation in the Covid-19 mortality rates. The research highlights the crucial need for investment in both climate action and public health infrastructure as key lessons from the Covid-19 crisis, so countries can be better prepared for similar disasters in future.

The researchers used data from 110 countries empirically linking the Covid-19 mortality rates and a set of country-specific factors, consisting of pre-Covid-19 characteristics and a set of social, economic and health responses to the outbreak of the virus. Key findings include:

- Individualistic societies fared significantly worse than collectivist ones in coping with Covid-19, resulting in much higher mortality rates. In the context of Covid-19, individualistic societies are known to be less engaged with social distancing and other measures as they are likely to be less concerned about the favourable impacts of such actions on others.

- The greater the climate risk and the lower the readiness to climate change, the higher the risk of mortality from Covid-19.

- Countries that were better prepared for the climate emergency were also better placed to fight the pandemic. The data showed that these had consistently lower fatality rates.

- Public health capacity in terms of both health expenditures and number of hospital beds; the share of the elderly population; and economic resilience are important factors in fighting a pandemic

Gulcin Ozkan, Vice Dean (Staffing) and Professor of Finance at King’s Business School who is one of the authors of the research said: “Scientists have long established links between climate change and pandemics. Climate change is known to drive wild-life closer to people, which in turn, paves the way for viruses that are harmless in wild animals to be transmitted to humans with deadly consequences.

“In addition, the role of both extreme hot and cold weather in increasing mortality and of warmer climates in spreading diseases have been widely recognised. Given such significant role of climate change in health outcomes, and particularly in mortality, our research clearly establishes this link between climate risk, culture and the Covid-19 mortality rate.

“It’s time more countries take the climate emergency seriously and governments should invest in the infrastructure that could have prevented further deaths”.

Complications of premature birth decline in California

June 17, 2020

More of the youngest and smallest California preemies are going home from the hospital without any major complications, a Stanford study has found.

California’s most vulnerable premature babies are now healthier on average when they go home from the hospital, according to a new study led by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine and the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative.

Between 2008 and 2017, the proportion of the smallest and most premature California infants who survived until hospital discharge without major complications of their early birth increased from roughly 62% to 67%, and those with major complications had fewer of them.

The study was published online June 18 in Pediatrics.

“When a family takes their baby home from the hospital, we want them to have an infant that’s as healthy as possible,” said the study’s lead author, Henry Lee, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at Stanford. “Survival without major complications is one way we take into account that survival alone isn’t our only goal.”

The senior author is Jeffrey Gould, MD, professor of pediatrics and the Robert L Hess Endowed Professor.

About 1 in 12 California babies are born prematurely, arriving at least three weeks early, and about 1 in 100 are born 10 or more weeks before their due date. In the last 50 years, survival rates for very premature babies have greatly improved, Lee said, but some preemies continue to experience severe complications after birth, such as lung problems, infections, digestive disease, brain injury, brain hemorrhage and vision loss. Although prior studies had examined changes in the rates of individual complications of prematurity, none had addressed whether complications as a whole were declining among a large population of preemies in California.

Hospitals working together

California hospitals have been working together since 2007 to help neonatal intensive care units improve outcomes for babies. To promote this goal, they formed the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative. Headquartered at Stanford, the collaborative has conducted many projects to improve preemies’ health, such as studying best practices for resuscitating preemies in the delivery room and figuring out how to support breast-milk expression for mothers who deliver prematurely.

The new study focused on the smallest and most premature babies, those born 11 to 18 weeks early or who weighed 0.88 to 3.3 pounds at birth. It included 49,333 infants who were in the NICUs of 143 California hospitals between 2008 and 2017. The study did not include infants who died at birth or who had severe congenital abnormalities.

The researchers analyzed the infants’ medical records to look for the presence of major complications of premature birth. Between 2008 and 2017, the percentage of very premature or very small infants in California who survived without major complications improved from 62.2% to 66.9%. There was a significant decline in mortality of these infants over the same period. The complications whose incidence decreased most were necrotizing enterocolitis, a disease in which intestinal tissue dies, which declined 45.6%; and infections, which declined 44.7%.

Fewer complications per infant

Among preemies who did have complications, they had fewer of them. The number of infants in the study with four or more separate complications declined 40.2% between 2008 and 2017, the number with three complications declined 40.0% and the number with two complications declined 18.7%.

“It was really encouraging to me that we found that babies were less likely to have multiple morbidities,” Lee said, adding that this means care is improving across the board, even for the sickest preemies.

The performance of California’s neonatal intensive care units became more uniform for most complications of prematurity, with less variation between hospitals. However, there is still room for improvement; the study estimates that if all hospitals matched the performance of the top 25% of the state’s NICUs, an additional 621 California preemies would go home from the hospital without major complications each year.

The California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative is helping health care providers at all NICUs learn from each other, Lee said. “We’ve started trying to see which hospitals are having very good outcomes, or have perhaps improved significantly over the last few years, so that we can disseminate the knowledge they have gained from their experience,” he said.

For families of premature babies, the new findings have a hopeful message. “It’s a hard situation when a family suddenly faces premature birth,” Lee said. “But we can tell them that we have taken care of many babies born at this age, and we’ve gotten better. That would hopefully be something of a reassurance.”

Other Stanford co-authors on the study are biostatistician Jessica Liu, PhD; Jochen Profit, MD, associate professor of pediatrics; and Susan Hintz, MD, professor of pediatrics and the Robert L. Hess Family Professor. Lee, Profit, Hintz and Gould are members of the Stanford Maternal & Child Health Research Institute. Lee is a member of Stanford Bio-X.

The study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R01 HD087425).

HEALTH CARE PARTNERS

Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Nurse Burnout in the US

Megha K. Shah, MD, MSc1; Nikhila Gandrakota, MBBS, MPH1; Jeannie P. Cimiotti, PhD, RN2; et alNeena Ghose, MD, MS1; Miranda Moore, PhD1; Mohammed K. Ali, MBChB, MSc, MBA3

Author Affiliations Article Information February 4, 2021

JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036469. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469

Key Points

Question What were the most recent US national estimates of nurse burnout and associated factors that may put nurses at risk for burnout?

Findings This secondary analysis of cross-sectional survey data from more than 3.9 million US registered nurses found that among nurses who reported leaving their current employment (9.5% of sample), 31.5% reported leaving because of burnout in 2018. The hospital setting and working more than 20 hours per week were associated with greater odds of burnout.

Meaning With increasing demands placed on frontline nurses during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, these findings suggest an urgent need for solutions to address burnout among nurses.

Abstract

Importance Clinician burnout is a major risk to the health of the US. Nurses make up most of the health care workforce, and estimating nursing burnout and associated factors is vital for addressing the causes of burnout.

Objective To measure rates of nurse burnout and examine factors associated with leaving or considering leaving employment owing to burnout.

Design, Setting, and Participants This secondary analysis used cross-sectional survey data collected from April 30 to October 12, 2018, in the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses in the US. All nurses who responded were included (N = 3 957 661). Data were analyzed from June 5 to October 1, 2020.

Exposures Age, sex, race and ethnicity categorized by self-reported survey question, household income, and geographic region. Data were stratified by workplace setting, hours worked, and dominant function (direct patient care, other function, no dominant function) at work.

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcomes were the likelihood of leaving employment in the last year owing to burnout or considering leaving employment owing to burnout.

Results The 3 957 661 responding nurses were predominantly female (90.4%) and White (80.7%); the mean (weighted SD) age was 48.7 (0.04) years. Among nurses who reported leaving their job in 2017 (n = 418 769), 31.5% reported burnout as a reason, with lower proportions of nurses reporting burnout in the West (16.6%) and higher proportions in the Southeast (30.0%). Compared with working less than 20 h/wk, nurses who worked more than 40 h/wk had a higher likelihood identifying burnout as a reason they left their job (odds ratio, 3.28; 95% CI, 1.61-6.67). Respondents who reported leaving or considering leaving their job owing to burnout reported a stressful work environment (68.6% and 59.5%, respectively) and inadequate staffing (63.0% and 60.9%, respectively).

Conclusions and Relevance These findings suggest that burnout is a significant problem among US nurses who leave their job or consider leaving their job. Health systems should focus on implementing known strategies to alleviate burnout, including adequate nurse staffing and limiting the number of hours worked per shift.

Introduction

Clinician burnout is a threat to US health and health care. At more than 6 million in 2019,2 nurses are the largest segment of our health care workforce, making up nearly 30% of hospital employment nationwide.3 Nurses are a critical group of clinicians with diverse skills, such as health promotion, disease prevention, and direct treatment. As the workloads on health care systems and clinicians have grown, so have the demands placed on nurses, negatively affecting the nursing work environment. When combined with the ever-growing stress associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, this situation could leave the US with an unstable nurse workforce for years to come. Given their far-ranging skill set, importance in the care team, and proportion of the health care workforce, it is imperative that we better understand job-related outcomes and the factors that contribute to burnout in nurses nationwide.

Demanding workloads and aspects of the work environment, such as poor staffing ratios, lack of communication between physicians and nurses, and lack of organizational leadership within working environments for nurses, are known to be associated with burnout in nurses. However, few, if any, recent national estimates of nurse burnout and contributing factors exist. We used the most recent nationally representative nurse survey data to characterize burnout in the nurse workforce before COVID-19. Specifically, we examined to what extent aspects of the work environment resulted in nurses leaving the workforce and the factors associated with nurses’ intention to leave their jobs and the nursing profession.

Methods

Data Source

We used data from the 2018 US Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Service Administration National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN), a nationally representative anonymous sample of registered nurses in the US. The weighted response rate for the 2018 NNRSN is estimated at 49.0%.6 Details on sampling frame, selection, and noninterview adjustments are described elsewhere.7 Weighted estimates generalize to state and national nursing populations.6 The American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3 method was used to calculate the NSSRN response rate.6 This study of deidentified publicly available data was determined to be exempt from approval and informed consent by the institutional review board of Emory University. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies

Variables and Definitions

Data were collected from April 30 to October 12, 2018. We generated demographic characteristics from questions about years worked in the profession, primary and secondary nursing positions, and work environment. We included the work environment variables of primary employment setting and full-time or part-time status. We grouped responses to a question on dominant nursing tasks as direct patient care, other, and no dominant task. We included 3 categories of educational attainment (diploma/ADN, BSN, or MSN/PhD/DNP degrees) and whether the respondent was internationally educated. Other variables included change in employment setting in the last year, hours worked per week, and reasons for employment change.

We categorized employment setting as (1) hospital (not mental health), (2) other inpatient setting, (3) clinic or ambulatory care, and (4) other types of setting. Workforce stability was defined as the percentage of nurses with less than 5 years of experience in the nursing profession.

We used 2 questions to assess burnout and other reasons for leaving or planning to leave a nursing position. Nurses who had left the position they held on December 31, 2017, were asked to identify the reasons contributing to their decision to leave their prior position. Nurses who were still employed in the position they held on December 31, 2017, and answered yes to the question “Have you ever considered leaving the primary nursing position you held on December 31, 2017?” were asked “Which of the following reasons would contribute to your decision to leave your primary nursing position?”

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from June 5 to October 1, 2020. We used descriptive statistics to characterize nurse survey responses. For continuous variables, we reported means and SDs and for categorical variables, frequencies (number [percentage]). Further, we examined the overlap of the proportions who reported leaving or considered leaving their job owing to burnout and other factors. We then fit 2 separate logistic regression models to estimate the odds that aspects of the work environment, hours, and tasks were associated with the following outcomes related to burnout: (1) left job owing to burnout and (2) considered leaving their job owing to burnout. We controlled for nurse demographic characteristics of age, sex, race, household income, and geographic region and reported odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Two separate sensitivity analyses were performed: (1) we used a broader theme of burnout defined as a response of burnout, inadequate staffing, or stressful work environment for the regression models; and (2) we stratified the regression models by respondents younger than 45 years and 45 years or older to examine difference by age.

We used SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), with statistical significance set at 2-sided α = .05. We used sample weights to account for the differential selection probabilities and nonresponse bias.

Results

The 3 957 661 nurse respondents in 2018 were mostly female (90.4%) and White (80.7%). The mean (weighted SD) age of nurse respondents was 48.7 (0.04) years, and 95.3% were US graduates. The percentage of nurses with a BSN degree was 45.8%; with an MSN, PhD, or DNP degree, 16.3%; and 49.5% of nurses reported that they worked in a hospital. The mean (weighted SD) age of nurses who left their job due to burnout was 42.0 (0.6) years; for those considering leaving their job due to burnout, 43.7 (0.3) years (Table 1).

Of the total sample of nurses (N = 3 957 661), 9.5% reported leaving their most recent position (n = 418 769), and of those, 31.5% reported burnout as a reason contributing to their decision to leave their job (3.3% of the total sample) (eTable in the Supplement). For nurses who had considered leaving their position (n = 676 122), 43.4% identified burnout as a reason that would contribute to their decision to leave their current job. Additional factors in these decisions were a stressful work environment (34.4% as the reason for leaving and 41.6% as the reason for considering leaving), inadequate staffing (30.0% as the reason for leaving and 42.6% as the reason for considering leaving), lack of good management or leadership (33.9% as the reason for leaving and 39.6% as the reason for considering leaving), and better pay and/or benefits (26.5% as the reason for leaving and 50.4% as the reason for considering leaving). By geographic regions of the US, lower proportions of nurses reported burnout in the West (16.6%), and higher proportions reported burnout in the Southeast (30.0%) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the overlap between leaving or considering leaving their position owing to burnout and other reasons. For both outcomes, the highest overlap response with burnout was for stressful work environment (68.6% of those who left their job and 63.0% of those who considered leaving their job due to burnout).

The adjusted regression models estimating the odds of nurses indicating burnout as a reason for leaving their positions or considering leaving their position revealed statistically significant associations between workplace settings and hours worked per week, but not for tasks performed, and burnout (Table 2). For nurses who had left their jobs, compared with nurses working in a clinic setting, nurses working in a hospital setting had more than twice higher odds of identifying burnout as a reason for leaving their position (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.41-3.13); nurses working in other inpatient settings had an OR of 2.26 (95% CI, 1.39-3.68). Compared with working less than 20 h/wk, nurses who worked more than 40 h/wk had an OR of 3.28 (95% CI, 1.61-6.67) for identifying burnout as a reason they left their position.

For nurses who reported ever considering leaving their job, working in a hospital setting was associated with 80% higher odds of burnout as the reason than for nurses working in a clinic setting (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.55-2.08), whereas among nurses who worked in other inpatient settings, burnout was associated with a 35% higher odds that nurses intended to leave their job (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.05-1.73). Compared with working less than 20 h/wk, the odds of identifying burnout as a reason for considering leaving their position increased with working 20 to 30 h/wk (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.85-3.55), 31 to 40 h/wk, (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.24-3.98), and more than 40 h/wk, (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 2.73-4.85).

The sensitivity analysis results in which a broader classification of burnout was used showed a similar relationship between odds of burnout and working more than 40 h/wk (OR, 3.86; 95% CI, 2.27-6.59) for those who left their job (OR, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.13-3.31). Stratification by those younger than 45 years and 45 years or older did not significantly change the findings. Figure 3 shows the overlap in nurses who reported burnout and other reasons for leaving their current position or considering leaving their current positions. The greatest overlap occurred in responses of burnout and stressful work environment (68.6% of those who reported leaving and 59.5% of those who considered leaving) and inadequate staffing (63.0% of those who reported leaving and 60.9% of those who considered leaving).

Discussion

Our findings from the 2018 NSSRN show that among those nurses who reported leaving their jobs in 2017, high proportions of US nurses reported leaving owing to burnout. Hospital setting was associated with greater odds of identifying burnout in decisions to leave or to consider leaving a nursing position, and there was no difference by dominant work function.

Health care professionals are generally considered to be in one of the highest-risk groups for experience of burnout, given the emotional strain and stressful work environment of providing care to sick or dying patients.8,9 Previous studies demonstrate that 35% to 54% of clinicians in the US experience burnout symptoms.10–13 The recent National Academy of Medicine report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being,” recommended health care organizations routinely measure and monitor clinician burnout and hold leaders accountable for the health of their organization’s work environment in an effort to reduce burnout and promote well-being.1

Moreover, it appears the numbers have increased over time. Data from the 2008 NSSRN showed that approximately 17% of nurses who left their position in 2007 cited burnout as the reason for leaving, and our data show that 31.5% of nurses cited burnout as the reason for leaving their job in the last year (2017-2018). Despite this evidence, little has changed in health care delivery and the role of registered nurses. The COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated matters; for example, understaffing of nurses in New York and Illinois was associated with increased odds of burnout amidst high patient volumes and pandemic-related anxiety.

Our findings show that among nurses who reported leaving their job owning to burnout, a high proportion reported a stressful work environment. Substantial evidence documents that aspects of the work environment are associated with nurse burnout. Increased workloads, lack of support from leadership, and lack of collaboration among nurses and physicians have been cited as factors that contribute to nurse burnout. Magnet hospitals and other hospitals with a reputation for high-quality nursing care have shown that transforming features of the work environment, including support for education, positive physician-nurse relationships, nurse autonomy, and nurse manager support, outside of increasing the number of nurses, can lead to improvements in job satisfaction and lower burnout among nurses. The qualities of Magnet hospitals not only attract and retain nurses and result in better nurse outcomes, based on features of the work environment, but also improvements in the overall quality of patient care.

Self-reported regional variation in burnout deserves attention. The lower reported rates of nurse burnout in California and Massachusetts could be attributed to legislation in these states regulating nurse staffing ratios; California has the most extensive nurse staffing legislation in the US.20 The high rates of reported burnout in the Southeast and the overlap of burnout and inadequate staffing in our findings could be driven by shortages of nurses in the states in this area, particularly South Carolina and Georgia. Geographic distribution, nurse staffing, and its association with self-reported burnout warrant further exploration.

Our data show that the number of hours worked per week by nurses, but not the dominant function at work, was positively associated with identifying burnout as a reason for leaving their position or considering leaving their position. Research suggests nurses who work longer shifts and who experience sleep deprivation are likely to develop burnout. Others have reported a strong correlation between sleep deprivation and errors in the delivery of patient care.22,24 Emotional exhaustion has been identified as a major component of burnout; such exhaustion is likely exacerbated by excessive work hours and inadequate sleep.

The nurse workforce represents most current frontline workers providing care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature from past epidemics (eg, H1N1 influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome, Ebola) suggest that nurses experience significant stress, anxiety, and physical effects related to their work.27 These factors will most certainly be amplified during the current pandemic, placing the nurse workforce at risk of increased strain. Recent reports suggest that nurses are leaving the bedside owing to COVID-19 at a time when multiple states are reporting a severe nursing shortage.28–31 Furthermore, given that the nurse workforce is predominantly female and married, the child rearing and domestic responsibilities of current lockdowns and quarantines can only increase their burden and risk of burnout. Our results demonstrate that the mean age at which nurses who have left or considered leaving their current jobs is younger than 45 years. In the present context, our results forewarn of major effects to the frontline nurse workforce. Further studies are needed to elucidate the effect of the current pandemic on the nurse workforce, particularly among younger nurses of color, who are underrepresented in these data. Policy makers and health systems should also focus on aspects of the work environment known to improve job satisfaction, including staffing ratios, continued nursing education, and support for interdisciplinary teamwork.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, our findings are from cross-sectional data and limit causal inference; however, these data represent the most recent and, to our knowledge, the only national survey with data on nurse burnout. Second, our burnout measure is crude, and more extensive measures of burnout are needed. Third, 4 states did not have enough respondents to release data (Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota). However, these data were weighted, and they represent the most comprehensive data available on the registered nurse workforce. Fourth, nonresponse analyses of these data reveal underestimation of certain races/ethnicities, specifically Hispanic nurses, and small sample sizes limited analyses of burnout by race/ethnicity. Fifth, the public use file of the NSSRN does not disaggregate the MSN, PhD, and DNP degrees in nursing practice categories. Given that these job tasks can vary, we addressed this limitation by examining dominant function at work. Last, the response rate was modest at 49.0% (weighted). Despite these limitations, this analysis is most likely the first to provide an updated overview of registered nurse burnout across the US.

Conclusions

Burnout continues to be reported by registered nurses across a variety of practice settings nationwide. How the COVID-19 pandemic will affect burnout rates owing to unprecedented demands on the workforce is yet to be determined. Legislation that supports adequate staffing ratios is a key part of a multitiered solution. Solutions must come through system-level efforts in which we reimagine and innovate workflow, human resources, and workplace wellness to reduce or eliminate burnout among frontline nurses and work toward healthier clinicians, better health, better care, and lower costs.

Source:https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2775923

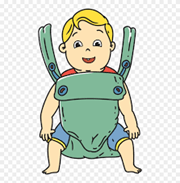

Babywearing” in the NICU

An Intervention for Infants With Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

Williams, Lela Rankin PhD; Gebler-Wolfe, Molly LMSW; Grisham, Lisa M. NNP-BC; Bader, M. Y. MD

Editor(s): Cleveland, Lisa M. PhD, Section Editor Author Information Advances in Neonatal Care: December 2020 – Volume 20 – Issue 6 – p 440-449

Abstract

Background:

The US opioid epidemic has resulted in an increase of infants at risk for developing neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Traditionally, treatment has consisted of pharmacological interventions to reduce symptoms of withdrawal. However, nonpharmacological interventions (eg, skin-to-skin contact, holding) can also be effective in managing the distress associated with NAS.

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to examine whether infant carrying or “babywearing” (ie, holding an infant on one’s body using cloth) can reduce distress associated with NAS among infants and caregivers.

Methods:

Heart rate was measured in infants and adults (parents vs other adults) in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) pre- (no touching), mid- (20 minutes into being worn in a carrier), and post-babywearing (5 minutes later).

Results:

Using a 3-level hierarchical linear model at 3 time points (pre, mid, and post), we found that babywearing decreased infant and caregiver heart rates. Across a 30-minute period, heart rates of infants worn by parents decreased by 15 beats per minute (bpm) compared with 5.5 bpm for infants worn by an unfamiliar adult, and those of adults decreased by 7 bpm (parents) and nearly 3 bpm (unfamiliar adult).

Implications for Practice:

Results from this study suggest that babywearing is a noninvasive and accessible intervention that can provide comfort for infants diagnosed with NAS. Babywearing can be inexpensive, support parenting, and be done by nonparent caregivers (eg, nurses, volunteers).

Implications for Research:

Close physical contact, by way of babywearing, may improve outcomes in infants with NAS in NICUs and possibly reduce the need for pharmacological treatment.

***** See the video abstract BELOW for a digital summary of the study.

ROP: EARLY DIAGNOSIS TO AVOID BLINDNESS FOR BABIES

Dec 27, 2017 Ivanhoe Web

It’s a blinding eye disorder that affects as many as 16,000 preemies in the United States every year. See how a doctor in Oregon is pioneering ways to keep these babies from going blind.

***UPDATE: Michael F. Chiang, M.D., is now the Director of the National Eye Institute at the National Institutes of Health. A Very Interesting Interview can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8AqvQae3sJY

Evaluation of the Neonatal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment and Mortality Risk in Preterm Infants With Late-Onset Infection

Noa Fleiss, MD1; Sarah A. Coggins, MD2; Angela N. Lewis, MD3; et alAngela Zeigler, MD4; Krista E. Cooksey, BA3; L. Anne Walker, BA5; Ameena N. Husain, DO3; Brenda S. de Jong, BSc6; Aaron Wallman-Stokes, MD1; Mhd Wael Alrifai, MD5; Douwe H. Visser, MD, PhD6; Misty Good, MD3; Brynne Sullivan, MD4; Richard A. Polin, MD1; Camilia R. Martin, MD7; James L. Wynn, MD8 Author Affiliations Article Information Original Investigation Pediatrics February 4, 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036518. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36518

Key Points

Question How useful is the neonatal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment for identification of preterm infants at high risk for late-onset, infection-associated mortality?

Findings In this multicenter cohort study of 653 preterm infants with late-onset infection, the neonatal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was associated with infection-attributable mortality. Analyses stratified by sex or Gram stain of pathogen class or restricted to less than 25 weeks’ completed gestation did not reduce the association of the neonatal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score with infection-related mortality.

Meaning In a large, multicenter cohort, the single-center–validated neonatal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was associated with mortality risk with late-onset infection in preterm infants, implying generalizability.

Abstract

Importance Infection in neonates remains a substantial problem. Advances for this population are hindered by the absence of a consensus definition for sepsis. In adults, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) operationalizes mortality risk with infection and defines sepsis. The generalizability of the neonatal SOFA (nSOFA) for neonatal late-onset infection-related mortality remains unknown.

Objective To determine the generalizability of the nSOFA for neonatal late-onset infection-related mortality across multiple sites.

Design, Setting, and Participants A multicenter retrospective cohort study was conducted at 7 academic neonatal intensive care units between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019. Participants included 653 preterm (<33 weeks) very low-birth-weight infants.

Exposures Late-onset (>72 hours of life) infection including bacteremia, fungemia, or surgical peritonitis.

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcome was late-onset infection episode mortality. The nSOFA scores from survivors and nonsurvivors with confirmed late-onset infection were compared at 9 time points (T) preceding and following event onset.

Results In the 653 infants who met inclusion criteria, median gestational age was 25.5 weeks (interquartile range, 24-27 weeks) and median birth weight was 780 g (interquartile range, 638-960 g). A total of 366 infants (56%) were male. Late-onset infection episode mortality occurred in 97 infants (15%). Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves for mortality in the total cohort ranged across study centers from 0.71 to 0.95 (T0 hours), 0.77 to 0.96 (T6 hours), and 0.78 to 0.96 (T12 hours), with utility noted at all centers and in aggregate. Using the maximum nSOFA score at T0 or T6, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for mortality was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.84-0.91). Analyses stratified by sex or Gram-stain identification of pathogen class or restricted to infants born at less than 25 weeks’ completed gestation did not reduce the association of the nSOFA score with infection-related mortality.

Conclusions and Relevance The nSOFA score was associated with late-onset infection mortality in preterm infants at the time of evaluation both in aggregate and in each center. These findings suggest that the nSOFA may serve as the foundation for a consensus definition of sepsis in this population.

Source:https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2775925

PREEMIE FAMILY PARTNERS

Safe Rides Home for Smaller Babies

Special Interest Group Update

Heidi Heflin, MN RN CNS CPSTI Laura Siemion, RNC-NIC BSN CPST

Helping caregivers select and properly use an appropriate child safety seat should be a part of every neonatal program (Bull & Chappelow, 2014; O’Neil et al., 2019). Child safety seats are highly effective in reducing the likelihood of death and injury in motor vehicle crashes, and for children less than 1 year old, a child safety seat can reduce the risk of fatality by 71% (Hertz, 1996).

Unfortunately, many babies may be poorly protected during their first car rides. One research study showed 93% of newborns left a university hospital inadequately buckled up (Hoffman et al., 2014). Although some nurses may feel uncomfortable addressing car seat safety, an unpublished 2020 national survey from NANN found that 112 of 113 nurse respondents said they had “addressed child passenger safety (CPS) for parents/caregivers during newborn hospitalization” within the past 6 months (Chappelow et al., 2020).

When it comes to preterm and low-birth-weight infants, special consideration must be given to transportation safety. In particular, the physiologic immaturity and low weight of these infants must be considered when selecting an appropriate type and model of child safety seat.

Motor vehicle injuries are a leading cause of death among children in the United States (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, n.d.). Every day in 2018, three children were killed and an estimated 520 were injured in U.S. traffic crashes (National Center for Statistics and Analysis, 2020). Many deaths and injuries could be prevented with proper use of a child safety seat, which includes choosing a seat appropriate for the child.

To understand how child safety seats help prevent death, one must understand crash dynamics. The National Child Passenger Safety Certification Training (2020) describes that every vehicle crash is really three “crashes”. The first crash involves sudden deceleration of the vehicle, including hard braking, evasive maneuvers, and/or colliding with an external object. The second occurs as the occupant strikes something in the vehicle (in this case, a child hits the car safety seat shell and/or harness). The third crash involves the child’s internal organs continuing to move until they strike other organs or bones. A child safety seat decreases the severity of the second and third collisions by directing much of the crash energy into the child safety seat and away from the child.

A child safety seat is designed to protect a child in a crash or sudden stop in more than one way. It spreads crash forces across the strongest parts of the child’s body. For infants and young children, that means the seat must be placed with the child rear-facing so that, in a frontal collision, the force is dispersed over a wide area of the child’s back. The unproportionally large head, immature neck, and spine are protected by being encased in the child safety seat shell and by a snug-fitting harness securing the child at the shoulders and hips. A child safety seat helps the child’s body slow down more gradually than ‘the sudden stop,’ and prevents ejection from the car. Even at 30 mph, crash forces are severe. For instance, an unrestrained 10-lb baby in a 30-mph crash is thrown with 300 lbs of force.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Policy Statement “Transporting Children with Special Health Care Needs” provides guidance for selecting child safety seats for infants with special healthcare needs and asserts that a conventional rear-facing child safety seat, which allows for proper positioning of the preterm infant, should be used if the infant can maintain healthy vital signs while seated in a semi-upright position (O’Neil et al. 2019).

Selecting the appropriate child safety seat can be daunting, especially since there are almost 350 models of child safety seats currently offered for sale in the United States (J. J. Stubbs, personal communication, October 1, 2020). Each offers slightly different features. An “appropriate” seat is one that properly fits the newborn, fits the vehicle, and is convenient to use on every ride (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2020). The newborn’s weight, length, maturation, and associated medical conditions should all be considered when selecting a seat (Bull et al., 2009; reaffirmed 2018).

All child safety seats legally sold in the United States must meet Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) No. 213, which establishes many child restraint system requirements, including those related to crash performance, flammability, and labeling. Child safety seat labeling can help determine if the seat is compliant and how to use it properly (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2020). Requirements include a label on the plastic shell stating that the seat meets federal standards and a label with the date of manufacture. Model/manufacturer/”birthdate” labels should be used as a reference for investigating recalls.

Because child safety seat manufacturers generally set a specified lifespan (from 6 to 11 years) for their products, most models indicate an expiration date on labels or in the owner’s manual. Expired child safety seats should be destroyed or recycled, not used to transport a child.

The 2018 revised AAP policy statement, “Child Passenger Safety,” recommends that children ride rear-facing as long as possible, limited by the maximum weight and length allowed for use by their child safety seat instructions (Durbin et al., 2018).

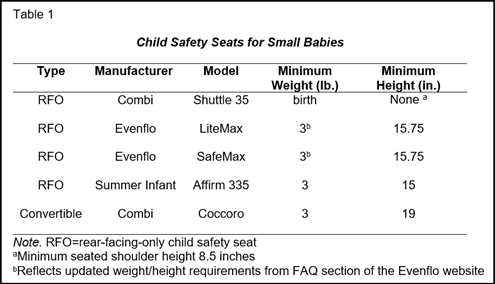

Determining which seat fits by weight is a good first step to narrow selection. Most rear-facing-only (RFO) safety seats allow use by infants beginning at 4 lbs. At the time this article was written, three RFO seats allow use beginning at 3 lbs, and one may be used “from birth.” Larger convertible or all-in-one seats typically allow rear-facing use starting at 5 lbs, though several are available that start at 4 lbs and one allows use beginning at 3 lbs. After disqualifying seats based on weight, minimum height requirements can be used to immediately narrow options. See Table 1 to learn more about child safety seats for small babies.

A close-to-comprehensive product list of all seats on the market, including their weight minimum and maximum, can be found on AAP’s Healthy Children website. The list is updated annually but is not revised between updates, so some new models may not be reflected. A current list of all child safety seats that are rated for infants under 4 lbs can be found in the free handout #173 Automobile Restraints for Children with Special Needs: Quick Reference List found on the SafetyBeltSafe U.S.A. website. This list is updated as products are introduced or discontinued.

When choosing between an RFO or convertible child safety seat, note that either can provide optimum comfort, fit, and positioning for the preterm or low-birth-weight infant (Bull et al., 2009; reaffirmed 2018) if carefully selected. RFO seats are lighter weight, have a handle for carrying, and usually can be snapped in and out of a base that remains installed in the vehicle. Convertible seats are larger, heavier, and meant to stay in the car. Despite their larger overall size, some convertible models may be an option for preterm infants if the harness system fits properly. Models that allow use by 4-lb children tend to be adjustable for use by very small infants. Convertible seats have a longer period of usefulness, allowing forward-facing use by children weighing up to 40–85 lbs, depending on the seat. They are often a good choice for lower-income families and hospital distribution programs.

However, child safety seat fit is more complicated than just considering the allowable weight and height requirements of a product. Several features contribute to how well a seat fits a tiny baby. One thing to consider is where the shoulder harness goes through the seat relative to the child’s shoulders. When any infant is riding rear-facing, the harness straps must go through slots that are at or below the infant’s shoulders. Therefore, for a preterm infant, a seat with very low shoulder strap slots (roughly 5–6 in. up from the seat cushion), is essential (Safe Ride News Publications, 2020).

Some seats come with crash-tested and approved adjustment methods specifically for tiny babies, such as boosting inserts and alternative harness threading methods. A harness must be able to be tightened snugly over the child’s body, judged by ensuring the webbing cannot be pinched between thumb and forefinger. In addition, the buckle strap (or “crotch strap”) may have an adjustment to place it closer and/or make it shorter, preventing an infant from sliding down or slumping into an unsafe position (Bull et al., 2009; reaffirmed 2018).

In general, child safety seat instructions direct the user to which approved and recommended adjustments are necessary for a safe, snug harness fit. (Note: While adjustability may greatly enhance the performance of a child safety seat for a small infant, making the necessary adjustments can be complicated and overwhelming.) A child passenger safety technician (CPST), a nationally certified educator in the field of occupant protection, is a resource that can help train the neonatal team, keep them up to date (AAP et al., 2014), and assist with solving complex child safety seat problems.

Used seats are acceptable only if the parent or caregiver knows the seat’s history and that it has all pieces, including instructions. They must be certain that the seat has never been in a crash, is not expired, and has no unresolved recalls. Reused seats are often missing pieces, especially the inserts for newborns. Refer to the child safety seat instructions to account for every piece (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2020).

Be aware that counterfeit seats are appearing with greater frequency at child safety seat installation stations, and they may be making their way to hospitals. These are often bought online at a “value” price and provide little or no protection in a crash. Sometimes it is difficult to identify a fake seat. Counterfeit child safety seats do not meet federal safety standards, often lack required labels on the seat shell and are made of inferior materials. Ask a CPST for help if you have doubts about whether a seat complies with federal safety standards.

Infants with certain temporary or permanent physical conditions may be at risk when placed in the semi-reclined position of a conventional seat and may travel more safely in a car bed certified to FMVSS 213 standards (Bull et al., 2009; reaffirmed 2018). To screen for tolerance in the semi-upright seating position, an infant should be observed in an appropriate child safety seat for valid results. To learn more about Car Seat Tolerance Screening (CSTS), refer to the AAP’s clinical report, Safe Transportation of Preterm and Low Birth Weight Infants at Hospital Discharge.

While some CPSTs are nurses, a nurse does not need to be a CPST to help protect infants in cars. To manage risk, a working group of experts convened by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) recommends that hospitals employ a CPST to train staff, assist in annual competency checks, and provide hands-on advice and guidance to families when questions arise beyond the nurse’s skill level (AAP et al., 2014). A CPST with additional certification through Safe Travel for All Children: Transporting Children with Special Health Care Needs would be an especially valuable resource.

One way to find CPSTs is to visit http://cert.safekids.org. CPSTs can assist in the development of policies, procedures, and guidelines, train neonatal nurses on how to better protect their patients, and ensure that practices/institutions stay abreast of new products and updates to best practice recommendations. Additional sources for education, training, and resources for neonatal professionals and parents of preterm infants are listed at the end of this article. Neonatal nurses play a critical role in promoting CPS. They are a trusted source of information and have an established relationship with families in their communities. In an NHTSA motor vehicle occupant survey (2020), caregivers self-reported their behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge related to auto occupant safety, including the transport of children specifically. Of the responding caregivers, 48% indicated they received child restraint information and advice from a nurse or doctor.

The CPS field needs neonatal nurses as a vital link to caregivers. Ensuring that nurses know the basic criteria for child safety seat selection and use helps them to accurately educate parents, document child safety seat use upon discharge, and conduct car seat tolerance screenings. CPSTs welcome a nursing partnership to keep kids safe in cars.

Neonatal Passenger Safety Resources:

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Healthy Children site: www.HealthyChildren.org

- Automotive Safety Program: www.preventinjury.org, information about transporting children who have certain medical conditions or have undergone procedures.

- National Center for Safe Transportation of Children with Special Health Care Needs: https://preventinjury.pediatrics.iu.edu/special-needs/national-center/

- Child Safety Seat Manufacturers’ sites: search by manufacturer name on search engine

- National Child Passenger Safety Board: www.cpsboard.org, the Safe Transportation of Children: Checklist for Hospital Discharge includes guidelines specific to neonates.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA): www.nhtsa.gov

- Safe Kids Worldwide: www.safekids.org, find a CPST with training in special transportation needs

- Safe Ride News: www.saferidenews.com, Selecting an Appropriate Child Safety Seat for a Tiny Baby fact sheet.

- Safety Belt Safe U.S.A.: www.carseat.org, offers caregiver and professional child passenger safety technician assistance call Safe Ride Helpline 800.745.SAFE (English), 800.747.SANO (Spanish).

Source: http://nann.org/publications/e-news/january2021/special-interest-group

What pregnant women should know about climate change

From low birthweight to preterm birth, pregnant women should know the potential health impacts of climate change. Learn how to keep yourself and your child healthy in a changing climate. This guide will explain how air pollution and heat matters to preterm birth and how you can keep you and your child healthy in a changing climate.

A Parents Guide to their Premature Babies Eyes

What is ROP? Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a potentially blinding disease, which in the United States affects several thousand premature infants every year. It was unknown prior to 1942 because premature infants did not survive long enough to show the effects of ROP. With improvements in the medical care of the smallest premature infants, the rate and severity of ROP has increased. The diagnosis of ROP is made by an ophthalmologist who examines the inside of the eye. Premature infants qualify for eye examinations based on several factors, including the birth weight. Although, a high percentage of examined babies will show some degree of ROP, most will not require surgery. Nevertheless, premature babies require lifelong follow-up by an ophthalmologist because of their increased risk for eye misalignment, amblyopia, and the need for glasses to develop normal vision. Interested in learning more?

Please access the Parent Guide Below:

INNOVATIONS

Video Abstract: “Babywearing” in the NICU: An Intervention for Infants with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

Video Author: Lisa M. Grisham Published on: 07.28.2020

We describe the impact of infant carrying or “babywearing” on reducing distress associated with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome among infants and caregivers. Heart rate was measured in a neonatal intensive care unit pre- (no touching), mid- (20 minutes into babywearing), and post-babywearing (5 minutes later). Across a 30-minute period, infants worn by parents decreased 15 beats per minute (bpm) compared to 5.5 bpm for infants worn by an unfamiliar adult, and adults decreased by 7 bpm (parents) and nearly 3 bpm (unfamiliar adult). Babywearing is a non-invasive and accessible intervention that can provide comfort for infants diagnosed with NAS.

Both preterm and post-term birth increases risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Posted ON 04 FEBRUARY 2021

The causes of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are complex and remain unclear. A recent study, involving more than 3.5 million children, now shows that the risk of ASD may slightly increase for each week a baby is born before or after 40 weeks of gestation.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, affecting 1% to 2% of children worldwide. Children with this disease cannot initialize or take part in social communication and have repetitive behaviours. The reasons may be genetic and related to environmental factors, and there are still a lot of unsolved puzzles in this field.

A group of scientists analysed data of 3.5 million children born in Sweden, Finland or Norway between 1995 and 2015. The goal of the study was to explore a potential correlation between gestational age (at which week a child is born) and the risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder. The results show that the children born at term (in weeks 37-42) had the lowest risk rate of 0.83. This risk rate represents the percentage of babies with ASD in the specific group: a risk rate of 0.83 means that less than one baby born at term had ASD in the study population. For the babies born preterm in weeks 22-31, the risk rate for ASD was about 1.67, while for the babies born preterm in weeks 32-36 the risk rate was 1.08. Finally, post-term birth, in weeks 43-44, was associated with the highest risk rate observed (1.74).

The results suggest that preterm and post-term birth can be related to ASD. However, the main limitation of the study is the lack of information on the potential causes for either pre- or post-term birth. More research is required to clarify the link between pre- and post-term birth and ASD.

The study is based on nationwide data from Sweden, Finland, and Norway, made available from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program “RECAP preterm” (Research on European Children and Adults born preterm, www.recap-preterm.eu). Please see the following link for more information regarding the RECAP preterm project and EFCNI’s involvement: www.efcni.org/activities/projects-2/recap

Premature babies have a higher risk of dying from chronic disease as adults

NTB THE NORWEGIAN NEWS AGENCY – 28 January 2021

Those that were born prematurely had a 40 percent higher risk of dying from chronic disease than the rest of the population, according to a new study.

A new study shows that people born prematurely have double the risk of dying from heart disease, chronic lung disease and diabetes as adults, compared to the rest of the population. The study includes 6.3 million people from Norway, Sweden, Finland and Danmark. It was led by professor Kari Risnes at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU.

A full term pregnancy lasts 40 weeks. If a child is born before week 37, it’s considered premature.

The study shows that the general risk of death among people below the age of 50 is 2 in every 1000. For those born prematurely, this risk is 40 per cent higher.

Around 6 per cent of children in Norway are born before their full term.

“We already know that those who are born prematurely have a higher risk of dying as children and as young adults. Now we’ve shown the risk of death from chronic diseases before the age of 50,” Risnes says to NRK (link in Norwegian).

Doctors should now take into consideration whether someone was born prematurely when working with patients, according to Risnes.

“We already know that those who are born prematurely have a higher risk of dying as children and as young adults. Now we’ve shown the risk of death from chronic diseases before the age of 50,” Risnes says to NRK (link in Norwegian).

Doctors should now take into consideration whether someone was born prematurely when working with patients, according to Risnes.

Health Professional News

An inside look at the Children’s Minnesota neonatal transport program

For neonates, time is precious. Our neonatal transport team is able to transport newborns in need from any distance in the Upper Midwest. They receive specialized training to provide the safest transfer of patients, which can be done by ambulance, helicopter, fixed-wing plane or our critical care rigs. Transport service is available around the clock, seven days a week — the neonatal team is equipped to implement treatments such as nitric oxide and active cooling therapies immediately upon arrival at the hospital and during the transport.

“As medical director for the Children’s Minnesota neonatal transport team, I am extremely proud of the care our highly skilled team provides. Each year our team partners with referring hospitals around the Upper Midwest to transport hundreds of neonates to our Children’s Minnesota NICUs,” said Heidi Kamrath, DO, neonatal transport medical director and neonatologist. “We know that while most babies are born healthy, emergencies happen. Our neonatologists are accessible 24/7 by phone and virtual care where available for consultation. When transport is needed, our team is dedicated to providing high quality compassionate care to the families we serve.”

Meet two valuable members of the Children’s Minnesota neonatal transport team: Andy Rowe, RRT and Alison Olson, APRN, CNP. Andy is a respiratory therapist and critical care transport coordinator, and Alison is a neonatal nurse practitioner and transport team lead.

Read on as they provide information about their role and the highly complex, important program that they help lead to improve outcomes for newborns.

Q. What’s your background and what do you do on the team?

Andy: My training is in respiratory therapy and I’ve been with Children’s Minnesota for 11 years. For the past 5 years, I’ve been on the neonatal transport team and have managed the day to day operations since 2018. I love working on this well bonded team as we go into outlying communities with the opportunity to make a difference for neonatal patients, families and our referral hospitals.

Alison: I have worked in NICU for the past 10 years and have been a Neonatal Nurse Practitioner at Children’s Minnesota since 2017. I now serve as the NNP transport lead to guide policy and practice for the team as well as the care of neonatal patients requiring transfer from a community hospital to Children’s Minnesota when they require a higher level of care. My work helps assure quality and best outcomes for all newborns that come to the NICU at Children’s Minnesota.

Q. Can you tell me about the capabilities you carry with you when you transport a newborn?

Andy: We are prepared with all the capabilities of our Level IV NICU including high frequency ventilation, nitric oxide and active body cooling. Many preterm infants transported need high frequency ventilation (HFV). HFV can be very beneficial in reducing the risk for chronic lung disease for these fragile infants, by providing them with protective lung ventilation. For infants with respiratory failure such as severe hypoxia, respiratory distress syndrome, ELBW babies (23-26 weeks), persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), pneumothorax, meconium aspiration syndrome, we also carry inhaled nitric oxide (INO) on our transport incubators. The benefits of INO is that when inhaled, it relaxes and dilates the pulmonary vasculature allowing for improved oxygenation.

The sooner we can institute these techniques, the better the outcomes because it can prevent long term lung damage. Our goal is “out the door in 30 minutes of a call” and helps assure these care interventions can be applied as soon as possible!

Q. In addition to advanced respiratory care capability, you mentioned that you have “active” body cooling available on transport. For babies that have suffered hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, is there criteria for when you may choose “passive” versus “active” body cooling?

Alison: When babies experience a hypoxic event or require resuscitation at delivery, community hospitals may start “passive” body cooling before we arrive. They may also be on the phone with Children’s Minnesota Physician Access or Neonatal Virtual Care for consult and continuing care guidance prior to our team arriving. Once we arrive, our transport team determines whether to use passive or active body cooling during transport.

Some of the decision making is based on proximity of the referring hospital because it takes some time to get the cooling machine set up and ready for cooling. If it is appropriate to initiate active body cooling, we use the Tecotherm Neo which is a blanket that is made up of tubes of water. The machine uses a thermometer to monitor the baby’s temp and sends that information to the blanket, adjusting the water temp as needed. It allows us to consistently cool the baby at a temperature of 33-34 degree Celsius quickly and safely. The treatment is continued once we reach Children’s Minnesota for 72 hours at which time we slowly bring their temperature back to normal as the treatment is completed. Total body cooling helps reduce secondary injury of the hypoxic insult and quick initiation is critical for best outcomes.

“The Future of Science is Appreciation of Disorder”- James Gleick

WARRIORS:

Over time, the science of Chaos has integrated into diverse sciences, providing broadened views, enhanced perspectives.

James Gleick on Chaos: Making a New Science

Mar 30, 2011

“Chaos is a kind of science that deals with the parts of the world that are unpredictable, apparently random . . . disorderly, erratic, irregular, unruly—misbehaved,” explains James Gleick, author of Chaos: Making a New Science. Gleick, one of the nation’s preeminent science writers, became an international sensation with Chaos, in which he explained how, in the 1960s, a small group of radical thinkers upset the rigid foundation of modern scientific thinking by placing new importance on the tiny experimental irregularities that scientists had long learned to ignore. Two decades later, Gleick’s blockbuster modern science classic is available in ebook form—now updated with video and modern graphics.

KAT’S CORNER

Over the past 5 months we have been living in chaos as we have experienced moving during the pandemic. In the process of selling our previous home we lived in an apartment for four months before settling into our new house. As shown in the photo above moving into an old house built in 1918 has come with its bundle of chaos. From getting the entire house re-plumbed to considering new electricity and heat we are navigating new beginnings in a time of chaos. One thing that has kept us centered is our love and concern for our PTSD cat, Gannon. Our efforts to provide him with familiar things and routines on a daily basis has calmed his fears and helped him to experience a sense of normalcy, which has helped us to experience a sense of normalcy. If we conscientiously choose to experience periods of peace and familiarity within this chaotic journey we are all on, we will always navigate home.

Foiling the Dead Sea

•Jul 19, 2018 Di Tunnington

The Dead Sea is the lowest place on earth, and 9 times saltier than the ocean. Taking the Hydrofoil out was a lot harder than I expected as the Salt caused drag for the foil! Check it out.